Cassils’ employs their own body as both the material and protagonist of their art, contemplating the histories of LGBTQI+ violence, struggle and survival.

This Autumn, HOME in Manchester presents the first major UK exhibition of the artist’s work accompanied by a new performance piece entitled Human Measure that was made in collaboration with choreographer Jasmine Albuquerque alongside a group of trans and non binary dancers.

Here, Cassils discusses representation, mediation and the evolution of their art.

What’s your earliest memory of engaging with art or of wanting to be an artist?

I think I always wanted to be an artist. I started to draw very early on; I would spend four to five hours a day drawing. It was a natural form of expression for me and it was also one of the few things that people told me that I was good at. I wasn’t very academic, but I was brought up in quite an academic household so art was the one thing where I could really shine. I think I also felt a natural inclination towards it because it allowed me to express things which I maybe I didn’t have words for and which seemed to uncover themselves in my work. In that way it was good for my mental health too.

When did you become interested in exploring performance as a medium?

I went to art school, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, when I was about 18 years old. It’s one of two really good art schools in Canada and although I had a love of art, I went there not really knowing much. I guess I didn’t really come from a family that was especially engaged with the arts and so I had found things on my own. Anyway, this art school was actually, unbeknownst to me, a super radical, experimental place, especially in the 1970s, when a lot of American draft dodgers from the Vietnam war had made their way up from New York City to Halifax, Nova Scotia of all places and the school became a bastion for conceptual and performance art.

Initially, I thought I wanted to paint, but when I realised all the sorts of possibilities that more contemporary forms offered, specifically the ability to get outside of the gallery and engage people in real time, that became very exciting to me. Then upon graduating in my early twenties, I moved to New York City and I became an intern at a space called the Franklin Furnace, which is one of the largest or maybe the only large non-profit organisation devoted to performance art. My job was to take all this portapak footage of performance works from the 1970s, digitise them and upload them onto a digital archive. This was in the nineties before anything was really online and it gave me this very firsthand experience of sifting through these incredible works. I think that informal education certainly influenced me.

In our recent interview with Marina Abramovic, she talked about inhabiting different bodies: her private body and her public body when she performs. Is this something you relate to?

I don’t really. Life is a performance. I would say that my work doesn’t really stop and end in a gallery space or in a performance, but I think it also depends on who you are and what your subjectivity is. If you’re a cis white woman who wanders through the world without much rupture of standards and norms that are anointed and celebrated, then maybe it’s possible for you to think of things in these parcelled ways, but as someone who has a sort of rupture in their day-to-day, I’d say that [performance] is not something that I get to start and stop at choice.

Another thing is that a lot of my work is deeply physical and requires hours and hours of physical preparation. Of course, the performance is very different – I would say it’s a moment of hyper-focus – but the preparations are also hyper-focused not just in relation to the physical training but also nutrition, sleep, mental state, all of that.

Are those preparations specific for each performance or more of a general lifestyle?

It’s both. Every work requires a different training and protocol, and that is an extension of my idea of the body as both an instrument and an image. Just as a painter would train their hand or develop certain new glazing techniques, the way in which I perform for different works requires radically different approaches to the body. For example, putting on 23 pounds of muscle in a certain amount of time is a very different training protocol to conditioning the bones and keeping your heart rate at above 70 beats per minute or training for disorientation.

So do you tend to develop ideas and plan performances quite far ahead?

Yes but the work that we’re going to present [at HOME in Manchester] is a little different because it’s the first time I’ve ever worked with other people’s bodies. I’ve certainly done some performances that involve other people’s bodies, but not in a physically rigorous way. This piece involves a choreographer and professional dancers of which I am not and so, the work has been much less about my body being prepared and more about the bodies of the dancers being prepared. We make sure, for example, that we have time to warm up and to cool down, which I’m told is not standard in the dance industry.

However, there’s a certain level that I keep my body at such that it can be applied on different directions and so I’m not starting from scratch each time. Dependent on the work, I will usually choose a certain amount of time in which I’m able to prepare properly. Although some of my work looks “risky” such as lighting myself on fire or pushing myself against ice, there’s a tremendous amount of preparation and risk assessment that goes on so that I can do the work in a sustained way. This isn’t about self-harm, if anything it’s about being able to sustain in an endured, safe way.

Have you ever started to develop an idea for a performance only to find it isn’t possible for whatever reason?

I’m sure I have although I feel really lucky that I’ve been able to manifest some pretty big feats. One of the most challenging works that I’ve done was fairly recently, during quarantine, in 2020. I’m a Canadian citizen and I immigrated to the US which took a very long time and was very expensive. In the process of that, I experienced a lot of homophobia and transphobia. It made me aware – even from a much more privileged position of being a Canadian national – of just how fraught that process is. So, when there were information leaks about the ways that migrants were being met at borders and put in cages for-profit in the United States – stories that were starting to circulate maybe two or three years ago – I found I couldn’t sleep at night, knowing what it would have been like to be in that position and really relating. [In response to that] I made a work with a good friend of mine rafa esparza who is an amazing performance artist and painter based in Los Angeles. We brought together 80 other artists and hired the nation’s sky-typing fleet to sky-type phrases to highlight and index these otherwise hidden for-profit sites of detention, working alongside 17 immigrant justice organisations. We also created an online campaign with a website, where you could enter your zip code and it would tell you exactly where you were in relation these sites.

It was a project that became incredibly difficult to pull off for many reasons. It was the height of Covid and funding it was really a challenge. We also came up against a lot of racism and xenophobia from funding bodies. I’ve made work that has, for the most part, involved my own subjectivity, but to then understand just how direct people were with their racism was shocking for me in a naive way. They tried to shut the project down; we were stopped by the FBI; we had trolls coming at our websites, and yet, we managed to pull it off.

So yes, there are things that I’ve tried to do that have been stopped, but artists have the gift of imagination and when we are met with a roadblock, it’s about figuring out ways that we can manage regardless even if it’s not along the traditional path.

You’ve spoken before about your body being a battleground. Can you elaborate on what you mean by that?

I think that the body is a battleground, but I guess my resistance to that idea is not wanting to personify or speak for the trans body. However, I do think that one’s personal stake is political and as I was saying before, depending on whether or not you fit the frame of what’s celebrated under a patriarchal system that is still under the auspice of white supremacy, your body is less or more of a battleground.

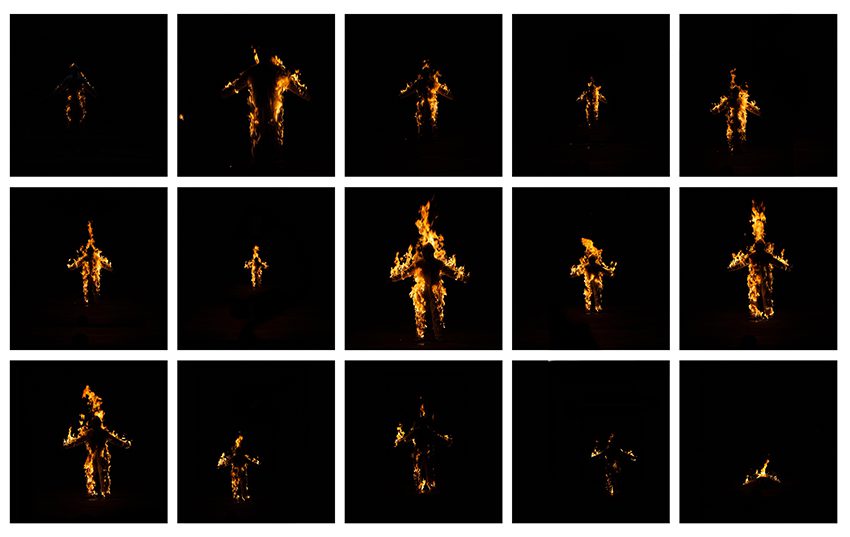

Works such as Inextinguishable Fire simulate acts of violence. What impact do you think this has on the viewer?

Yes, so with that work, which was made in 2015, I was really interested in the notion of fake news. At that time, there was a tremendous amount of uprisings in the US around the killing of young black men by police, and I was witnessing, in real time, how these uprisings were being framed by reportage as hoodlums and acts of looting. We’ve all seen that happen before, but it was shocking to see how easily people are manipulated by the way the media would frame things. The title of the piece, Inextinguishable Fire, references a work of the same name by German filmmaker Harun Farocki. His film is about the production of napalm, which was produced in a small factory in Ohio, in the United States. He explains how even though there were antiwar positions in the the US so much of the tax that people pay was contributing to this site of violence. There’s this moment in the film when he’s smoking a cigarette and he looks directly into the camera and says, “The embers of this cigarette burn at 300 degrees celsius, napalm burns at 3000 degrees.” Then, he extinguishes the cigarette into his flesh. It’s a horrifying act, but he’s not doing this to say this is the equivocation of trauma against the plight of the Vietnamese, it’s more that he’s using that cigarette burn as an approximation of the distance that we have from these acts of violence, and wars that we moved overseas on behalf of our nation states.

As someone who lives in Los Angeles, in the centre of what I call the industrialised production of imagery where you often see pictures and representations of war, far more actually than people are waging them firsthand having worked in the city for a long time, I became fascinated in the idea of the stunt. I went to stunt school in 2009/10 and I was especially interested in the full body burns, which is a stunt where you’re totally on fire. Often, you’re running through it so the fire can fly off of your face, but I was always surprised by how much a full body burn be like a self-immolation without the accoutrements of cinema around it, which is, of course, a gesture that someone will undertake when they have very little left to protest. I was interested in that sort of imagery.

Inextinguishable Fire is a live performance, which was performed at the National Theatre in London in 2015, with an accompanying film. The live performance starts when you see me being prepared – I have to be induced into a state of hypothermia because the danger isn’t that the fire burns through the fabric of your clothing and burns you, it’s that you’ll start to sweat and the sweat will boil on your skin and give you third degree burns. With the theatrical act, the audience would witness this entire production which is roughly half an hour of preparation and then only a 14 second burn. For the film, which is included in the HOME exhibition, I employ a single locked down zoom lens, which starts on a closeup of my chest. I’m wearing a raw canvas suit so it actually looks like you’re looking at an empty painting. And then, throughout the film, which is shot at 1000 frames per second with a Phantom camera, we see the camera sort of slowly opening and as it opens different sounds and contexts are laid into it. At first you think it’s an empty painting, then maybe it’s a painting on fire, then you realise it’s a burning body, but where are we? More and more information is revealed until you realise that we’re in an actual studio and that the image that you’ve been fed initially is manipulating you into thinking that it’s something that it isn’t. The sound is also very important. It starts from the viewpoint of inside my body: the sound of my first inhalation, the holding of my breath, the blood in my head, and at the end, you hear my body as if it’s on the other side of the room for me. So, you relate to being me and then being very separate from me.

This is a very long-winded answer, but I think, for me, it’s about how meditation affects both our ability to empathise and the notion of truth.

Is it important that your audiences understand the references or contexts of your work?

I think there’s something there for someone who knows nothing about the references – a physical, visceral feeling and connection that can be established without any knowledge – and also something there for people who are perhaps art historians and have more specific knowledge. I hope that the work is resonant for a large group of people, and I think the viscerality of physicality is a beautiful unifier, in a way, because we can all experience a kind of a cross identification despite what we encounter or where we come from.

So, I try to let the work speak for itself but I also think it’s important to set up a certain context so people can understand where you’re coming from. I am often making work about my own subjectivity and in certain instances, people have more or less understanding of that. Sometimes, there is an educational aspect to it, which honestly can be a bit tiring for me, but it can also be necessary although as time progresses, I think it’s becoming less and less necessary.

Your exhibition at HOME is a survey of ten years of your work as an artist. Do you think your approach to making art has changed at all during the years?

Yes, my approach has definitely changed. It’s a very different world to 10 years ago. 10 years ago, there was no word like non-binary, it wasn’t part of the common vernacular. There was a small trans subculture but if you didn’t medically transition then you didn’t really count. That was the sort of vibe amongst the trans community. So to make work from that space, to make work when there was no representation that was around being gender nonconforming or non binary was a different experience. That landscape has changed so the sort of work that I needed to do has changed.

Another massive change for me has been living in the US under the past president. Some would argue that Trump brought to the forefront many of the systemic inequities that already existed in the United States and that’s certainly true, but to see such a rollback of rights has been shocking. Right now there are so many conservative judges that have been appointed that there is the largest amount of bills in the state legislature ever in the history of the United States that are actively rolling back the rights of young trans people and literally trying to erase people. To live through that and to come from a time that was fairly supportive and open and free has definitely changed the way that I make work. I’d say that my work has become a lot more community-based and a lot more about collaboration. I’ve also been thinking about how I, as an artist, can help uplift other artists whose subjectivities may be different from mine such that we can create complex, varied arguments to educate, but also to create change and imagine different ways of being in this more oppressive world.

Your new performance piece was inspired by Yves Klein’s Anthropometries paintings. How so?

Klein is a cheeky bastard; he’s great, but nauseating. His Anthropometry series is his deconstruction of the nude – taking his international Yves Klein patented colour, and then using women as sort of living paintbrushes to create his works versus him sitting there and painting himself. The idea of using these women as an extension of his authorship was probably quite playful back then and in the spirit of Fluxus, but today it would definitely be cancelled. Anyway, my day job is that I’ve worked as professional athlete and a trainer for many years and when I peel a client off the generic blue gym after a hard workout, there’s often this impression of their shoulder blades and all the hair follicles, and I think, “Oh, we’ve made a Klein.”

I really have two ways of working: one is my artistic practice which is obviously supported by my physical practice, but I also have this deep knowledge of self-defence personal safety, wellness and the body. So, I started thinking what would it be like to make a work where rather than just engaging these issues in a sort of symbolic and metaphoric fashion, those that I worked with embodied these lessons and took them with them long after the curtain drops. As I dove into Klein, I found this little known fact, which was that he was an avid judo practitioner and had actually studied in Japan with the founding father of judo. He practiced daily and produced the very first Roman language how-to book on the “cutdowns” which is a series of black and white photographs of him performing how to do all the cutdowns with lead practitioners in Japan. He also opened a dojo in Paris.

So, I thought that it would interesting to think about sweat as a mark making device. Rather than women covering themselves with paint and being directed, what would it be like for the mark-making to come from a spirit of empowered labour? The choreographer and I started to hold workshops with a personal safety company in Los Angeles that statistically holds workshops for both men and women because statistically, men and women are attacked for very different reasons, but they’d never done anything for trans and non binary people. In the workshops, we brought trans and non binary dancers together and asked them: what do you wish would have been prepared for? What would you be like to be prepared for? What has happened to you? What skills would you like to learn? So, in real time, we learned these de-escalation techniques, but also physical self-defence movements that became a template for movement and informed the choreography of the piece as well as the painterly essence that comes from the body.

In terms of the actual piece, I’ve extended an argument that I’ve been making in one of my earlier works called becoming an image, which kind of deconstructs photography and plays with the idea of meditation. We turn the entire theatre into an analogue dark room, lit entirely by red safety lights. The floor is covered with a thin material that is is very tightly stretched and has been pre-soaked in a cyanotype solution. During twenty minutes of bombastic movement, there are these massive flashes of light. So, the viewer goes from barely being able to see to being overwhelmed with white light. At the very end of the piece, unbeknownst to the viewers, the dancers push this material from the floor into a twenty by three foot trough that sits downstage in front of the audience, and they proceed to wash and develop this massive photograph in realtime. Instead of a curtain drop, the work ends with this giant cyanotype print in this gorgeous blue, which faithfully indexes all the moments and the bodies that have fallen. In that way, it’s loosely inspired by Klein but it was really a response to thinking about how personal agency and mark-making have shifted and transcended through the progress of time.

After the performance and show, what’s next for you?

Where a lot of people slowed down during the pandemic, I feel like I was on speed maximum. Also, my wife’s a nurse, so she’s been on the front lines of this pandemic, and I think both of us really need a rest. There are lots of projects on the horizon, but I think I need a moment to reframe things before continuing forward.

“Cassils: Human Measure”, curated by Bren O’Callaghan, runs until 12 December at HOME, Manchester. For more information, visit: homemcr.org

Featured Image: Cassils, Encapsulated Breaths, Installation, Image Solutions, Stantion Museum Houston, Texas, 2018. Photo: Cassils with Alejandro Santiago. Courtesy of the artist

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.