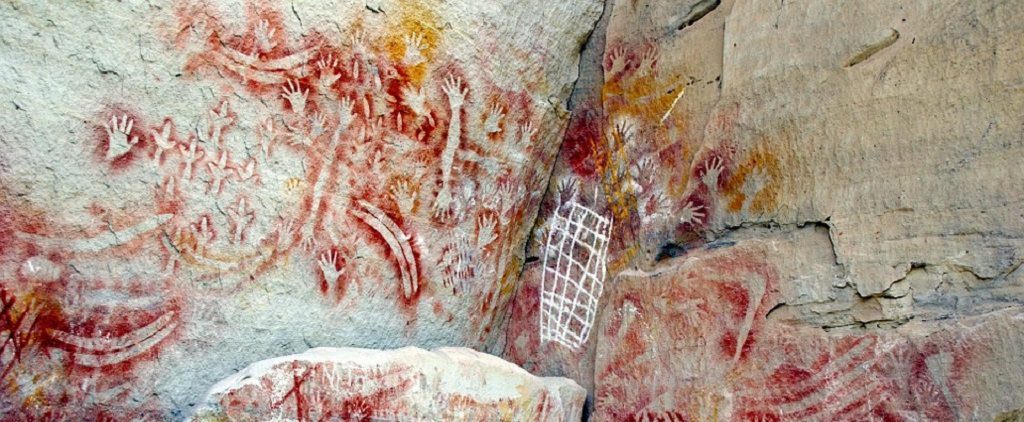

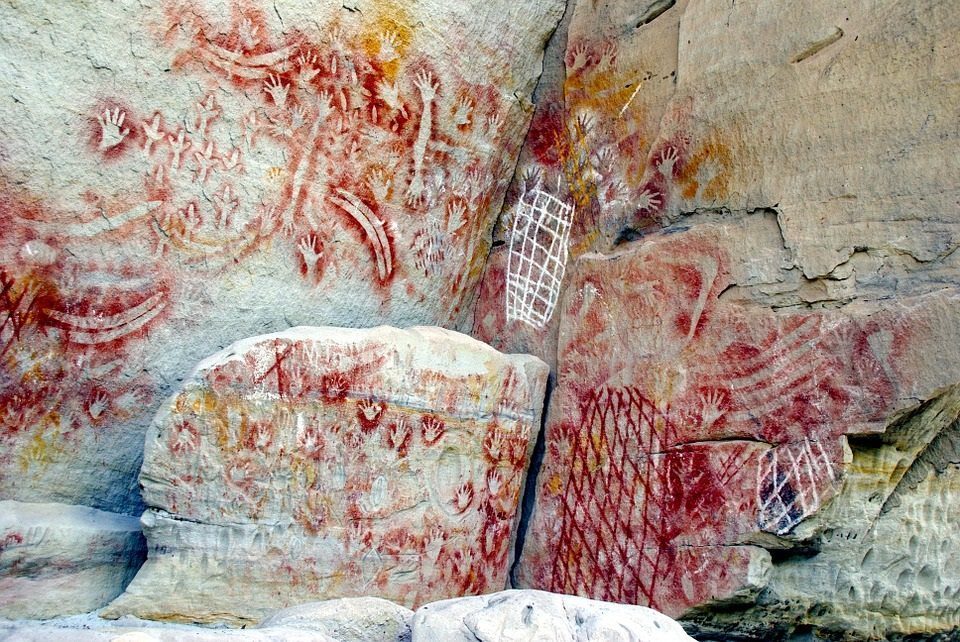

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]A[/dropcap] big shout out for our cave-dwelling antecedents. And we don’t mean a metaphorical shout either.

Could our, seemingly primitive, ancestors have been siting their cave paintings to maximise not only their visual impact, but their acoustic properties too? In a location as sense-accentuated as a deep cave, it does seem plausible.

Multimedia cave art: one more dent in the arrogant (and fragile) belief in the superiority of the post-industrial human.

To date, the exact purpose of Paleolithic cave paintings is unknown. Evidence suggests, however, that these ancient works of art are more than mere decorations. Cave paintings may have played a role in Paleolithic man’s religious rituals. Alternatively, some suggest that caves with many detailed paintings of animals might have served as spaces for hunting groups to bond and prepare for their hunts.

One popular theory proposes that the would-be painters of the Paleolithic era chose the places where they painted based on the acoustics of those locations in the caves. The originators of that theory reported a causal connection between the “points of resonance” in three French caves and the position of Paleolithic cave paintings. It was further hypothesized that music or chants played an integral role in cave rituals 20,000 years ago.

David Lubman, an acoustic scientist and fellow of the Acoustical Society of America, became interested in the subject due to his published expertise in sound reverberation. Lubman will share some of the insights from his research during Acoustics ’17 Boston, the third joint meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and the European Acoustics Association being held in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Many structures throughout history featured reverberant spaces because reverberant sound can be awe-inspiring. With that said, there is currently not enough evidence to suggest that these Paleolithic artists deliberately chose reverberant spaces for their paintings,” Lubman said.

“The main problem is that paintings on porous stone do not last, so we don’t know if such paintings existed and were lost over time or were never painted in the first place,” Lubman said. “Conversely, paintings on non-porous stone do persist and coincidentally spaces composed of non-porous stone walls are good spaces for sound reverberation. It’s important to note, however, that this does not mean that that these spaces were deliberately chosen for paintings because sound reverberates well in them. Correlation, after all, does not imply causality. As the old saying goes, crowing roosters do not cause the sun to rise.”

To answer the question, Lubman proposes a more systematic acoustic study of the reverberation in these caves.

“It can be challenging to use the human ear alone to identify the difference between reflection, which occurs when sound bounces back off a surface like a non-porous stone wall, and reverberance, which occurs when sound lingers long after an initiating action has been completed. That’s why it would be so helpful to have trained technicians with modern acoustical equipment testing these spaces,” Lubman said.

“If a significant degree of correlation between the location of the reverberant spaces and the presence of paintings were to be found, this alone would be an important discovery and opens up the possibility for new explanations,” Lubman said. “It could, for example, be entirely possible that Paleolithic cave artists initially chose spaces with non-porous stone because they were good canvasses for paintings — and then subsequently discovered that they were also great locations to generate reverberant sound.”

“If the expected correlation is not found, however, this would also be a vital step in helping clarify our understanding of what actually transpired in these caves,” Lubman said.

“Either way, the benefits of acoustical scientists and archaeologists collaborating on such studies are clear,” Lubman said. “Together, we can work towards developing a deeper understanding of our past.”

Source: Eurekalert/Acoustical Society of America

Image: Pixabay/MemoryCatcher

Some of the news that we find inspiring, diverting, wrong or so very right.