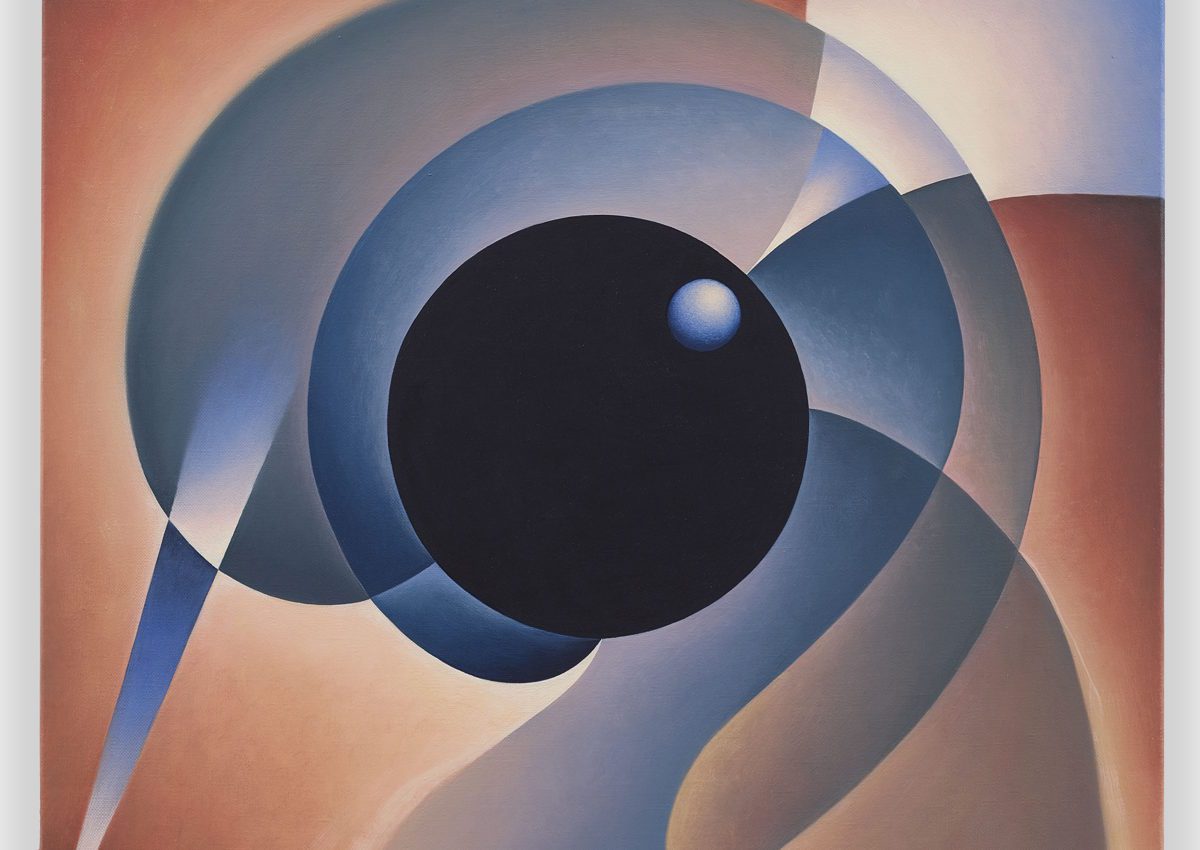

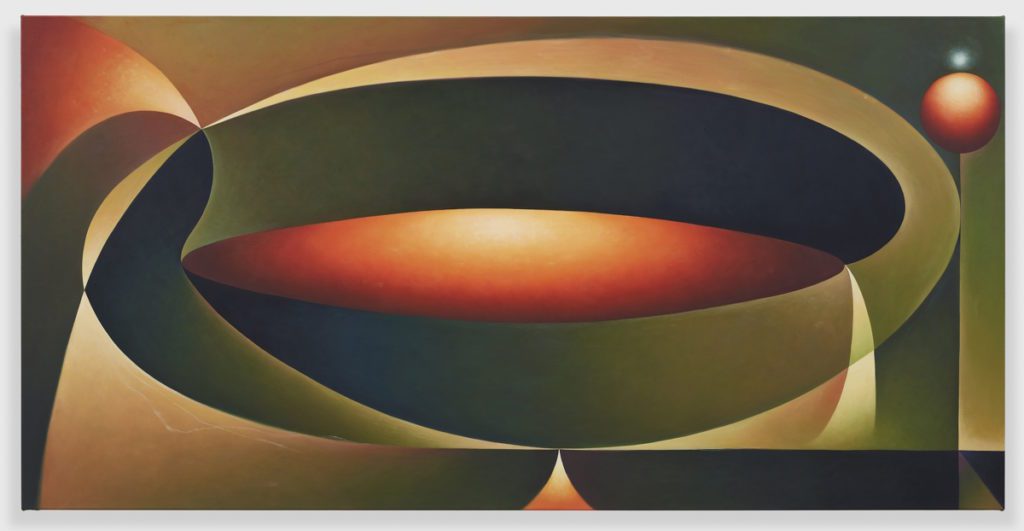

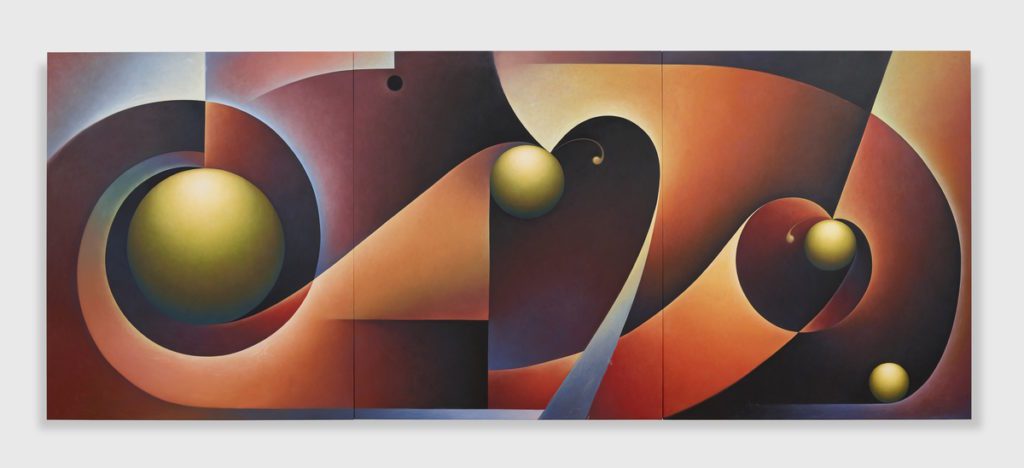

Reflecting a millennium struggling with implications of virtuality and organic entropy, New Zealander Angela Heisch’s (b. 1989) paintings capture supple forms in compositions that feel geometric and mechanistic. With their bendy abundance of orbs, squares, hidden light sources and indeterminate extensions and cavities, the works feel emotionally pregnant and meta without forcing a specific narrative. Alien and cosmic, abstract works like these operate on primal psychological senses, below mind and into the chthonic processes that compel us forward through our deeply felt, if chaotic and confusing, times.

Educated in the United States and on the back of her recent show at the Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London, Trebuchet had the opportunity to get Heisch’s take on her work, how she grasps abstraction, and where her style originated.

“Like many children, I spent a good bit of time drawing, also visiting my dad in his studio, as he was a cartoonist/storyboard artist. After a detour into music during my school years, I got serious about painting during undergrad, and developed a studio practice that’s continued to this day.

I begin with loose thumbnail sketches that are tested with pastel drawings. This stage feels very improvisational. I don’t really know how they’ll turn out, and I love that aspect of the process. From there, the pastels are translated into oil paintings and are built up in several relatively thin layers of paint. I try to let the paintings deviate from the pastel drawings, and usually the colour shifts quite a bit during the layering process. The paintings are finished with thin layers of paint combined with wax medium and linseed oil, that give them a softer texture, and drawn details that show more hand and gestural mark making.

The initial composition of a painting is sorted out through a series of thumbnails. They’re pretty rough, and just give a general idea of where I want to go with the work. From there, the thumbnails are translated into a line drawing on pastel paper. This stage is the most critical in terms of the overall composition of the eventual painting. I spend a good bit of time trying to get the right balance, density, and movement I want for the piece. Next I start to think about colour through chalk pastel. Based on the line composition I think about what general colour I want the work to be washed with, like warm reds and browns versus earthy greens and blues—it’s pretty broad. The pastels are figuring out colour because they’re easily layered and it’s relatively inconsequential to change directions mid way through the drawing. Once the pastel is finished, I’ll decide if it should become a painting. Sometimes the pastels don’t translate so well into painting, which is a mistake I’ve learned the hard way a handful of times. Another line drawing is then sketched out onto primed linen, and some alterations in composition are often made during this stage. The first few layers of oil paint are directly referencing the pastel drawing, but the last few layers tend to focus more on the direction of the painting, letting it become its own thing separate from the pastel.

I have too many inspirations to name, but recently I’ve been looking at Tullio Crali, J.B. Blunk, Giorgio de Chirico, Dorothea Tanning, Martin Johnson Heade, Art Nouveau jewellery and furniture, Lee Bontecou, Joan Miró, Leonora Carrington, Remedies Varo, Agnes Pelton, and baroque painting. In this particular body of work for “Low Speed Highs” I was inspired by Italian futurist tendencies, like how they approach movement and space. I wanted to achieve some of the clunkiness of artists like J.B. Blunk with the rich ornament of the baroque and Art Nouveau.

The reintegration of drawing into my practice has been really important. It’s allowed me to be intentional within the paintings, while allowing myself to be more explorative with the pastels. The immediacy of drawing has been a satisfying part of my practice that I can’t get as easily through painting because of the drying time with oils. I’ve always been a very intuitive painter, and was fighting those instincts for some time, lumping a lack of intention in with intuition. Exploration is such a key part of my work, and I hope that’s an experience the viewer has too.

I don’t want to give away much about my next body of work, just in case that changes, but in terms of process, I’m trying to integrate the mark making from my pastel drawings into my paintings.

Emotion plays a pretty big role in the work. My personal feelings and emotions drive the mood of the pastels in those early planning stages. Throughout the process of drawing and painting, I’m switching my brain on and off between being completely driven by colour, and then stopping to see what I’ve done. Additionally, emotion is an important subject in the paintings themselves. Sometimes the paintings are of nothing but a depiction of a feeling, such as playfulness, solitude, a fracturing, an imposing posture. Though I don’t think of my work as primarily figurative, there’s a sense of animation brought to life through emotion.

The emotion I was focused on conveying in “Low Speed Highs” was one of a motivated movement, but with a slight lag due to the clunkiness of the forms I mentioned earlier. There’s an element of fullness and density that’s thematically carried throughout my work and I hope to have achieved that feeling through the heaviness of the forms in these latest paintings.

I think for me the most successful works have been those that feel fresh and concise. My paintings take at least a month to make, and tend to lose their “freshness” by the 500th hour of staring at them, so when I feel both surprised and fully satisfied at how they turn out, I’m pretty happy. If I had to choose the most successful piece from this current show, I would say “Rolled Up Hills”-it’s my largest piece to date (14 feet wide), and although it took ages to finish, it still somehow ended up feeling just born. It was really fun thinking about landscape at that scale.

People have reacted in all sorts of ways to my work, which I think is the beauty of abstraction. It’s always interesting to see the range of associations people bring to the work—some so specific to their own experiences, some environmental, others more psychological. Abstract painting is so generous in that way, and abundant with cues for anyone’s taking.

Of course, People should start wherever they want. I don’t want to tell the viewer what they should see or how they should feel when they look at my work—I think that’s up to them. I like to use repetitive and tangible forms in the work as a way to give the viewer something to grab onto. In my most recent work, these are the glowing orbs and rectangular shapes. They have a recognizable dimension and are usually the starting point for the unfolding landscape or gestural movement around them. But I’m always surprised by how specific people can get with the work. I don’t intend for the work to be of any specific places or figures, but that’s the beauty of abstraction: people are able to walk away with a multitude of various meanings, often influenced by how they’re feeling in that moment, on that day.”

Angela Heisch is represented by Pippy Houldsworth Gallery.

Images courtesy of the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle