Just as expert chess players scrutinize a board to calculate their next moves, UT Dallas cognitive neuroscientists are studying the way these players' brains work to better understand how visual information is processed.

By deciphering how humans process visual information, researchers are uncovering new ways to improve eyewitness testimony, enhance teaching methods or increase people's ability to learn more efficiently.

Behavioral findings appear in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General (in press). Boggan and another PhD student, Chih-Mao Huang of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, had a related Journal Club paper in the Nov. 23 issue of the Journal of Neuroscience. The neuroimaging findings appear in the July 20 issue of Neuroscience Letters.

Study participants viewed a series of interleaved chess game boards and faces, noting whether each presentation matched the previous game position or face. With faces, chess experts, recreational players and novices demonstrated a so-called congruency effect, considered a hallmark of face processing. But only chess experts demonstrated a congruency effect with chess, suggesting that they process chess games more holistically than less-experienced players.

Study participants viewed a series of interleaved chess game boards and faces, noting whether each presentation matched the previous game position or face. With faces, chess experts, recreational players and novices demonstrated a so-called congruency effect, considered a hallmark of face processing. But only chess experts demonstrated a congruency effect with chess, suggesting that they process chess games more holistically than less-experienced players.

In another study, the researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to map the reactions inside the players' brains when they viewed faces, chess positions, randomized chess positions and other objects. While typical brain areas associated with face recognition were not particularly responsive to chess game displays, other areas of the brain were identified that were sensitive to whether games were normal games or had pieces randomly placed about the board.

In another study, the researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to map the reactions inside the players' brains when they viewed faces, chess positions, randomized chess positions and other objects. While typical brain areas associated with face recognition were not particularly responsive to chess game displays, other areas of the brain were identified that were sensitive to whether games were normal games or had pieces randomly placed about the board.

The neuroscientists predict this newfound understanding of visual recognition will help with efforts to improve learning and increase expertise. If scientists understand how people naturally process information to reach a conclusion, they might be able to improve processing mechanisms or take other steps to help individuals make better use of information.

Source: University of Texas at Dallas

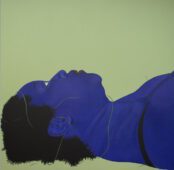

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle