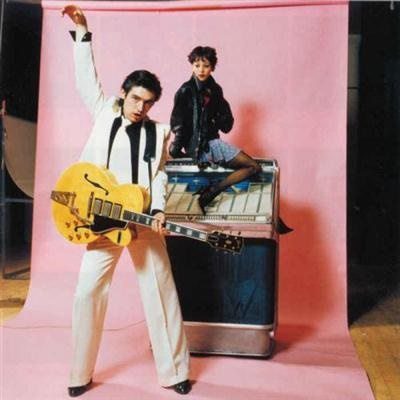

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he name Chris Spedding is likely to garner blank looks or ardent admiration, depending on your conversation partner.

While he hasn’t shown up regularly on the lists of major guitar gods since the early ‘80s, and was noticeably absent from Scarlet Page’s series of portraits of British guitarists last summer, he still deserves mention as one of the most prolific and talented guitarists of all time. Somewhere in the British session world genealogy between Big Jim Sullivan, Jimmy Page, and Chas Hodges (of Chas and Dave), Chris has played on innumerable other artists’ hits for nearly fifty years and even had one of his own, “Motorbikin’” (#14 in August 1975).

He has inspired melodic, non-ostentatious, thoughtful players and subtly left his mark on other guitarists from the ‘70s through the present day by way of his influence on The Pretenders’ James Honeyman-Scott, The Stray Cats’ Brian Setzer, The Cult’s Billy Duffy and James Stevenson, Franz Ferdinand’s Alex Kapranos, and The Smiths’ Johnny Marr. He is the mystery man in the shadows, even now.

Chris grew up in a comfortable upper-middle class home in Sheffield and Birmingham and started out studying violin at age nine. When he begged for a guitar four years later, desperate to start playing Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, and Lonnie Donegan songs and form his own rock ‘n’ roll/skiffle band, his parents grudgingly sent him to a local guitar instructor, hoping he would outgrow this phase.

Ironically this teacher converted him into a jazz snob. He spent his late teens and early twenties in London as a jobbing musician, playing in jazz groups, old-school orchestras, demo studios backing other artists, resort hotel and cruise ship house bands, a country-and-western band that toured American Air Force bases in Britain, and live back-up band for Dusty Springfield and, on one occasion in Sheffield, Sonny Boy Williamson.

Prog Rocker

A fellow jazz musician recommended Chris for the experimental, progressive, free form, psychedelic rock band Pete Brown and His Battered Ornaments. He ended up joining the other Battered Ornaments in firing Pete from his own band a few days before the Stones in the Park concert, but that didn’t keep Pete from recommending Chris to Jack Bruce, who was looking for a guitarist for Songs for a Tailor, his first solo album.

Jazz Fusion Pioneer

The next band to hire Spedding was Ian Carr’s jazz-fusion group, Nucleus. Although Chris wasn’t personally keen on fusion, he played the sometimes difficult, challenging  music magnificently. His contributions to Nucleus’s sound were so amazing that he seemed poised to become the next John McLaughlin. In fact, when he was presented with the opportunity to record an album of his own for the wild and woolly Harvest label, it was taken as a given that it would be jazz-heavy, proggy, and experimental, perhaps along the lines of Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart, or The Pink Fairies.

music magnificently. His contributions to Nucleus’s sound were so amazing that he seemed poised to become the next John McLaughlin. In fact, when he was presented with the opportunity to record an album of his own for the wild and woolly Harvest label, it was taken as a given that it would be jazz-heavy, proggy, and experimental, perhaps along the lines of Frank Zappa, Captain Beefheart, or The Pink Fairies.

To everyone’s what-the-fuck?! shock, ever the Americanophile, he instead delivered two roots rock albums that unapologetically tipped his hat to The Band, Bob Dylan, and Gram Parsons.

Session Man

Aside from a two-year hiatus to concentrate on The Sharks (1972-74), Spedding has been a session player since the late ‘60s. As one of the most in-demand A-list British session musicians – the equivalent of America’s legendary Wrecking Crew – his work days were heavily scheduled for a multifarious clientele: The Bay City Rollers, Acker Bilk, The Wombles, Elton John, John Cale, Donovan, Bryan Ferry, Roy Harper, Brian Eno, Mickey Jupp, Ginger Baker, David Essex, Harry Nilsson, Memphis Slim, and Jeff Wayne’s The War of the Worlds.

Temperamentally well suited to the work environment, Spedding navigated the sometimes shady studio world effortlessly, took every job offered if he wasn’t already scheduled for that time slot, and reliably showed up on time ready to work. If Chris Spedding had his own version of Eno’s famous Oblique Strategies deck (which he hadn’t heard of until a few days ago), there would only be two cards in it: “Show Up” and “Get On With It.”

The Sharks

When Chris was offered the spot of guitarist in The Sharks, with his all-time favorite bassist (Free’s Andy Fraser) he eagerly joined, turned his old American car into the fin-sporting Sharkmobile, and helped recruit Northern teenage prodigy Steve “Snips” Parsons on vocals. Chris honed his black-leather-clad greaser rocker image early on in The Sharks, cutting his long hair and wearing sharp-looking, well tailored clothes (often from Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s shop) at a time when the distressed-denim, homeless hippie look was still fashionable.

The Sharks were very much in the popular mold of bluesy, hard stadium rock, and should have been hugely successful. Fans maintain they should be doing reunion tours with Led Zeppelin, Queen, Foreigner, and Bad Company rather than being merely nattered about by lovers of obscure musical treasures.

But…sigh…after personnel shuffles and an abrupt end of label support, the band went their separate ways. Chris returned to session work and relaunched his solo career with the help of RAK Records’ legendary Mickie Most.

Rocker

In the wake of “Motorbikin’” were a series of classic albums Chris recorded for RAK – Chris Spedding (1976), Hurt (1977), Guitar Graffiti (1978), and I’m Not Like Everybody Else (1980). They were not commercially successful, and did not spawn a follow-up hit but were cult favorites among guitarists, particularly Chris Spedding’s “Guitar Jamboree” and the extended solos on Guitar Graffiti.

JOHNNY MARR: “My friends and I were all guitar players and music freaks on a big housing estate in South Manchester. We were all experts on guitar players, people like Pete Townshend, Paul Kossof, Mick Ronson, Rory Gallagher, Bill Nelson… these were all the guys we liked who were around during that time. Then when punk came out it was people like Tom Verlaine, Jimmy Scott, and Johnny Thunders. Chris was someone we all thought was cool.

I think I first heard about him playing with Eno and Bryan Ferry, and ‘Motorbikin’’, of course, because that was a big hit. We all thought the cover of Hurt was great, and the Flying V. Chris Spedding was one of the few guys who it was cool to like before punk and after punk too. He was cool and a bit mysterious.

I loved anything that had a guitar on it. No one ever mentions it, but it was a great period for pop music, because a lot of the records in the charts had great guitar riffs and sounds. I found out later that Chris played on some of that stuff.

The [1975] Top of the Pops appearance was very memorable. Chris really stood out, and the way he looked into the camera was odd in a great way. It was a really good performance, and “Motorbikin’” was a very striking record: quirky, with all the stops in it and an unusual lead vocal. The solo is good, short and to the point. I always remembered that performance on Top of the Pops. It was exciting.

I bought the Hurt album. I liked “Silver Bullet” and what he did with Bryan Ferry. Seeing him in the video for “Let’s Stick Together” was good, because back then it was rare to see him on TV. He had a strong image, and I knew he had played on some good records. He was unusual, because he was a free agent, so to speak. That was very interesting to me.”

Punk Proselytizer

Spedding had already experienced every major British music wave that came and went since the early ‘60s, so when his friend Chrissie Hynde took him to see The Sex Pistols perform in 1976, he knew instantly that punk was immensely important. Alone out of all of the U.K. music establishment, Chris told everyone who would listen about this great new band, going as far as producing their first demos for free just to further make his case to producers like Mickie Most and Chris Thomas.

At the infamous 100 Club punk festival, Chris, backed by The Vibrators, might have been a bit out of place, but he was the only established artist with a major recording contract who had the balls to show up and play. He later offered his demo production services to The Cramps in America.

The Slits’ Ari Up (Ariane Forster) lived with her mother Nora (later Mrs. John Lydon) and Chris for three years as pre-teen and teenager when she wasn’t at a West German boarding school. In a 2004 interview Ari remembered Chris’s interest in new music and his enthusiasm about The Sex Pistols:

ARI UP: “There was a huge, huge, huge, record collection. It’d be records, records everywhere. There wasn’t much furniture, because it had to be the records everywhere… He was really, really heavy into all types of music. He had a huge soul collection. His real love for music was also soul music, some real serious soul stuff, and of course R&B, needless to say, rock ‘n’ roll, all of that, old rock stuff, obviously Elvis Presley, great ‘50s do-wop stuff. But also a great collection, not that he got stuck in old times. He cut both edges. I noticed that at a young age, because obviously I was pretty modern, of course, when you’re twelve. He wasn’t stuck in the old times. What I found interesting is that he was always cutting edge, he kept up with the times, the modern music, all the modern shit that was going on at the time…

Chris was really on top of things. He went and saw the Pistols, and then he came back to my mom and said, ‘You’ve got to see this band. You’ve got to know about this band.’ So in a funny way I got introduced to the Pistols and to the whole punk scene just because of Chris.

That’s how The Slits [formed]. In a funny intriguing way Chris had something to do with my destiny in The Slits, without him meaning to maybe….

Think of the symptom of The Slits, being so ahead of time, being the first women ever to pick up instruments and play their own shit, being so influential in history, but at the same time being kids. I was actually a child star and didn’t know it. Throughout the whole entire Slits period, I was a teenager. The thing is, that hit me hard, to think that I could have been more developed or involved with Chris as far as him taking care of my musical direction.”

Rockabilly rebel

Chris relocated to the U.S. in 1978 to join rockabilly singer Robert Gordon’s backing band, on the assumption that he and Robert would be a songwriting team. The two became wildly popular during the resurgence of rockabilly and punk-psychobilly, but when a songwriting partnership did not materialize, Chris left to join The Necessaries for almost two years. He also struggled to find American record labels who would sign him as a solo artist and support his work, releasing only Enemy Within (1985), Café Days (1990), one compilation, and a few live albums in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

He did several North American and European solo tours, with and without Robert Gordon, sometimes assembling a power trio of musicians from Robert’s band, but never achieved the level of fame in the U.S. that he had enjoyed in the U.K. The two reunited in 2005 and continue to record and tour together.

with and without Robert Gordon, sometimes assembling a power trio of musicians from Robert’s band, but never achieved the level of fame in the U.S. that he had enjoyed in the U.K. The two reunited in 2005 and continue to record and tour together.

Americana Devotee

One Step Ahead of the Blues (2002), produced by Philippe Rault, heralded a return to Chris’s long-standing love of American music. His next albums Click Clack (2005), Pearls (2011), and the recent release of Joyland are a continuation of his exploration of blues, folk, rock ‘n’ roll, roots rock, and (once again) jazz.