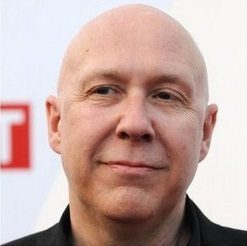

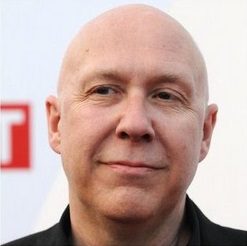

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]C[/dropcap]olin Vaines: writer, educator, film producer, cigar smoker and bon vivant is a busy man and his inscrutable demeanour contains an Old Media mix of interest, arch humour, confidence, and unsettling ease.

Whilst not a household name, since 1977 Vaines has helped a variety of talented writers, directors and producers see their film  become a reality. In 1987, he oversaw UK development for Columbia Pictures, working under David Puttnam’s lead and eventually becoming head of development for Puttnam’s production company, Enigma. From there, Vaines became Executive Vice-President, European Production and Development for The Weinstein Company.

become a reality. In 1987, he oversaw UK development for Columbia Pictures, working under David Puttnam’s lead and eventually becoming head of development for Puttnam’s production company, Enigma. From there, Vaines became Executive Vice-President, European Production and Development for The Weinstein Company.

Beyond production work, Vaines was artistic director of the Performing Arts Screenwriting Lab in the UK (working with a number of young writers who would end up behind films such as The Full Monty, Trainspotting, Billy Elliot, The Wind That Shakes The Barley, and The Guard and Calvary.

Currently, his writing graces the pages of the Huffington Post where he rails against the gentrification of the West End, fights against the closing of the velvet and sticks it to the mindless golems of commercial progress that would pave over the grimy promise of Soho.

And it’s here that we find him. Settling back into his chair puffing a cigar happily, Colin spoke to Trebuchet about his work in cinema and what (still) inspires him to make films.

—

Colin Vaines: I made my first film as a producer in 1990, which is rather a long time ago. What’s that?, 25 years ago? I started as a journalist because as a nipper my best friend’s father was a journalist on Fleet Street. His name was Jim Nicholson and was quite famous on Fleet Street, being known as the Prince of Darkness because he would cover all sorts of macabre crime stories.

I thought this guy was cool as fuck and I thought that if I became like him I could write about films or become a film critic, because I love movies. So I decided that around the age of ten. That’s what I wanted to do.

I left school when I was 17 and trained as a journalist. Within 18 months of that I was writing for Screen International [film trade paper]as a young reporter, which was like my film school. For the seven years I did that I interviewed directors, producers, writers, distributors, everyone.[quote]what Scorsese recognised,

was that I loved what he

was trying to do[/quote]

You saw everything of the industry, and that made me think that I really wanted to do this. Towards the end of my time there a friend of mine, who was running now what is called the BFI but at the time was called something very archaic: the National Film Finance Corporation, asked me to run the development fund. He just decided that I could do it, and it was brilliant because I could choose what we made. Every month we had meetings, where people in the industry would submit projects and we’d decide what we’d make.

How did you choose?

CV: I believe you must do the things you feel strongly about. If you just sign onto anything it’s a disaster because you end up with no coherent vision behind it. I’ve been very lucky in that I’ve worked with companies who from the very beginning have made what I consider to be quality films.

A quality film for me is… well the bottom line is story and character. My bottom line is ‘Tell me a good story with interesting characters’ and tell me a story where, when you start telling me the story, I have to ask ‘What happens next?’ Obviously not predictable stories or ones where I couldn’t give a shit.

I’m not particularly interested in redoing old films, although I wouldn’t say no to one or two things if there was a fresh take on it, but in general I’ve always been very lucky to work with high-end directors who’ve had original ideas. When I started working in production it was after I’d been running this development thing. I became a consultant for the parent body, which is now called British Screen, and then I was then hired by David Putnam to run development for him. David Putnam and Jeremy Thomas were two of the most interesting producers working in British screen.

Different than Simon Channing-Bell for example?

CV: Simon was completely brilliant, but Simon would work specifically with Mike (Leigh). The point of David and Jeremy was that they worked with a wide variety of interesting directors. I wanted to work with good people. It’s as simple as that and Putnam was the leading producer in England at the time, he’d done The Killing Fields, Chariots of Fire, The Mission and the thing about him was that he was a talent magnet that good writers wanted to work with.

He was also a role model to the degree that he liked to generate his own stories. For instance he’d find ideas in things that he read in the papers.

One day he opened the paper and saw a story on Sydney Schanberg, who had left his interpreter behind when he had to leave Cambodia and felt so guilty that he had to go back and find him again. A story which became the basis for The Killing Fields. This is the kind of thing that he did that I found attractive and why I wanted to work with him.

Another example was the film Memphis Belle, which was essentially a propaganda mission but Puttnam wanted to do the story of the guys behind that. The film itself is mainly about young people. The fact is that there had never really been a war film before that time that had shown people at the age they really were. Platoon is probably the one other one at that time. There hadn’t been a Second World War film that showed kids, nineteen or twenty years old, going off to doing this stuff. So what it was about was almost secondary to the fact that it’s exploring ten characters who were very young going through a remarkable phase.

It’s always about unique characters.

….within grander stories?

CV: Yes, in bigger stories. I really have been very lucky in the people that I’ve worked with. After working with Putnam I was out on my own for a while and then I ran one of the lottery companies, before being asked to work at Miramax and working with Harvey Weinstein, who is a difficult character, as well as a brilliant character.

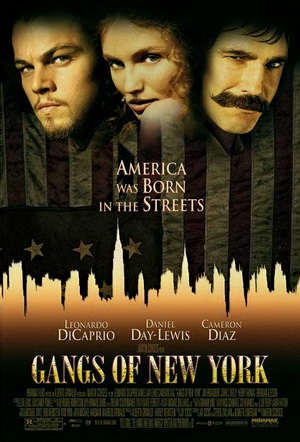

Again, (like Puttnam) he attracts people because of the clout he has with Miramax. When I started he’d just acquired Gangs of New York which no one had wanted to make, and that was my big introduction.

I just arrived at the company and I’m immediately taken to meetings with Scorsese, who has never dealt with anyone other than the head of the company, but Harvey wanted someone he trusted to be able to run the show and develop a relationship. What I loved, and what Scorsese recognised, was that I loved what he was trying to do. He wanted to tell a massive story, really about American society today, and how it was born.

Not on the West coast, which is of course what we know, with cowboys etc., but what happened on the East coast, which was supposedly so civilised but was actually a melting pot of cultures. And if you want to be slightly pretentious about it the essence of that, that story is about how America (or civilisation as we know it) tames the wild man in order to function and go forward.

The Gangs story has Leonard DiCaprio’s character creating himself as he goes along and I felt very drawn to that, as I’m very drawn to stories that have that father/son relationship.

I was never very close to my own father until the end of his life, so I felt I was missing a sort of father figure. Luckily I found that in the film industry with the senior people I worked with. Now I feel that I can give that back. It’s all about guiding people into what they want to do. I was working with William Monahan, who won an Oscar for The Departed, and produced his first film. That was about cultivating a situation where I put people around him who were able to help him make what he wanted to make.

By design I’ve managed to work with really good people that have taught me a lot. The point, with any of this stuff, is that you want to work with people that do that.

Cameras image by Mario Calvo

Editor, founder, fan.