The work of Paul Sietsema is so meta that it feels like a depth charge into the repressed backstory of Modernity. Making and representing media and associated art media Sietsema is the answer to the question how far can you take self-reflexive art for art-sake and still create effective work.

His artworks have the sort of abrasive aloof purview of art that begs to be hated, pearls clutched and drinks thrown, but that energy never fully spills into violence. Instead, the viewer is drawn in, sometimes trapped in a loop of reference, position, and meaning. His medium is the ‘what is art’ dialogue itself within his work, which he incubates like a virus and rewilds with each exhibition, publication, blog, conversation…

“Empire [A film by Sietsema, 2002] brings together a range of references from art and culture, engaging with the histories of architecture, sculpture, painting and photography, as well as film. In 2008 Sietsema said that he considered Empire ‘a kind of hard-edged sculpture, appropriating a number of avant-garde aesthetics steeped in different materials’.

In recreating [eminent art critic Clement] Greenberg’s apartment, in which hung Barnett Newman’s The Promise 1949 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York), a painting featuring two vertical lines that receives sustained attention in Empire, Sietsema could be seen to be reflecting on the continued influence of the critic and the movements he promoted.

The critic Saul Anton has suggested that with its emphasis on architecture ‘Empire seems to be interested in what empires are built on: the occupation of space’ (Anton 2003, p.183). The title of Sietsema’s work can also be seen as a reference to Andy Warhol’s Empire 1964, which consists of more than eight hours of continuous slow-motion black and white footage of the Empire State Building in New York. Like many of the other cultural references underpinning Sietsema’s film (including the image of Greenberg’s apartment and Bourgeois’s sculpture), Warhol’s Empire was produced in the mid-1960s – a historical moment in which one artistic ‘empire’, built around the work of abstract expressionists such as Newman and propounded by critics like Greenberg, was beginning to give way to other developments in painting, sculpture and film. Empire can be related to the work of avant-garde film-makers such as the American artist Stan Brakhage and the Canadian artist Michael Snow, both of whom began in the 1950s to make experimental films without clear narratives and which explored the formal movements and structures of the camera. Indeed, Sietsema has claimed that ‘Empire was partially meant to be “in memorium” of all the avant-garde aesthetics I was using’ (Latimer 2012, p.22).” – Tate Collection Description

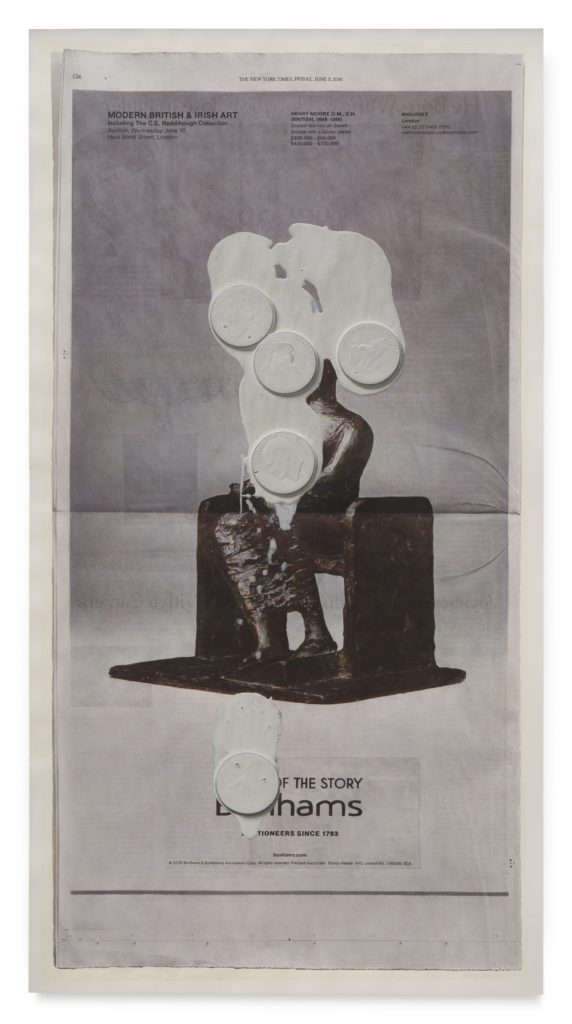

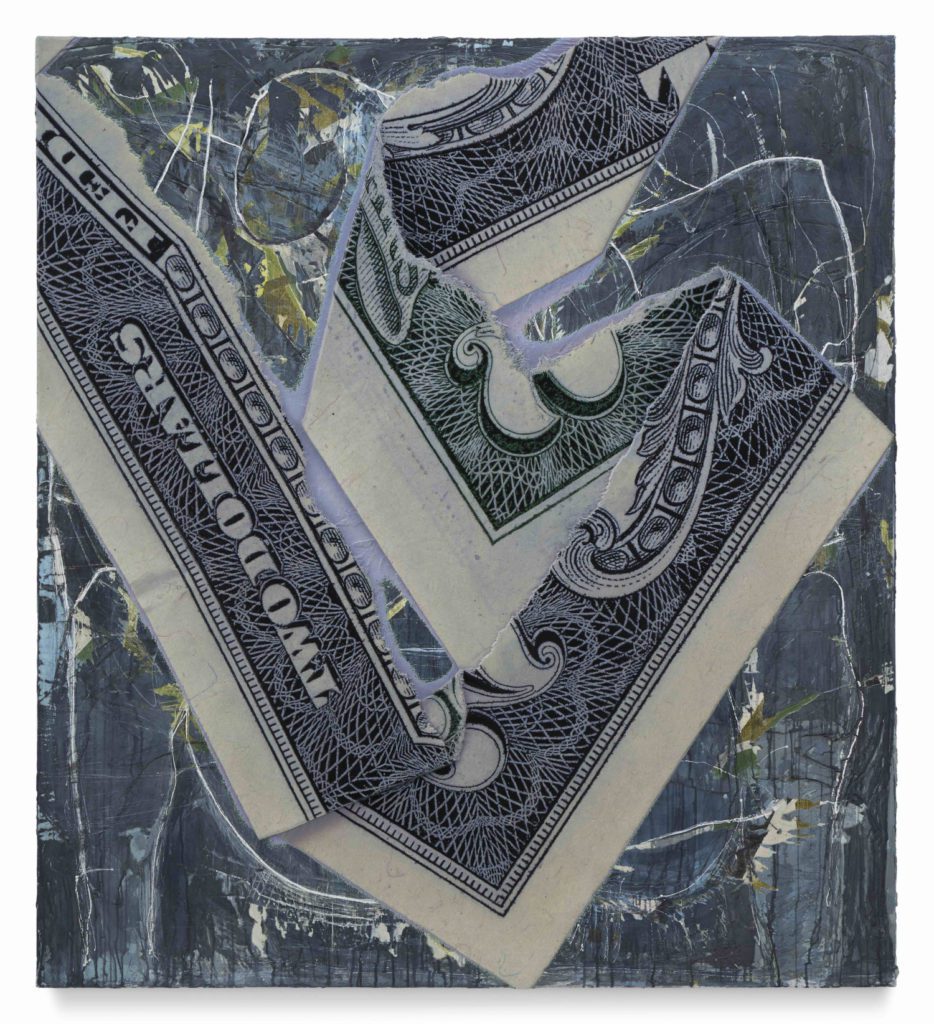

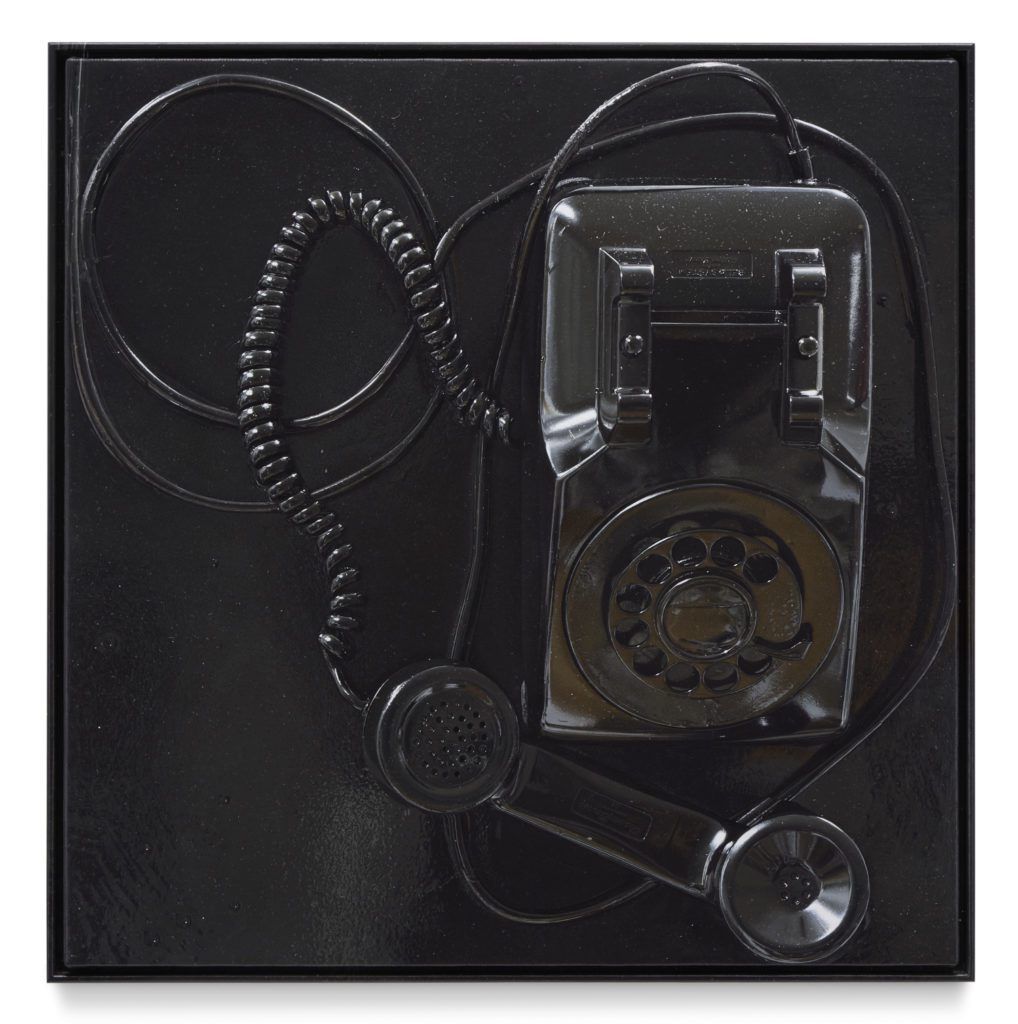

So why did he create this film? A quick summation of his process often runs as follows; multimedia artist Sietsema explores how imagery, form, and material affect our understanding of culture and history. Moving between discrete mediums at each stage of his studio process, he often cycles between physical making and digital image manipulation to create series of works that focus on tools of media; painter’s tools, newspapers, coins, rotary telephones, dust, paper currency, etc – art world ephemera and/or objects that might be said to have ‘currency’. In other words, he works with objects that carry a value beyond the implicit material of what they ‘are’. He renders these objects by hand with startling realism, employing labour-intensive techniques that mimic obsolete methods of mechanical reproduction and which almost by osmosis include the detritus that surround his process of making. In this way some might see a form of situationist entropy in his work where things are shop-worn by function of their function; dirty money, faded posters, torn tickets. He revels in their physical micro-history in contrast to the history carried by what these tokens represent, concepts which are worn by macro-historic movements.

Critically lauded in the US and perhaps something of a curator’s artist, Sietsema’s public profile remains niche in the UK. Born in 1968 he has had one-person exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Kunsthalle Basel. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2005, a DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) Fellowship in 2008, and a Wexner Center Residency Award in 2010. He lives and works in the media heartland of Los Angeles against which he feeds on the world of art rather than broader social movements (though they are tangentially related in some of Sietsema’s works) and a common current in his work is how the piece stares back at the viewer. There is an elitist judgement within his method where many pieces require a level of art knowledge to appreciate the play of meaning-construction that he’s referencing. Which doesn’t mean the work doesn’t operate without that knowledge, many of his works are accessible, maybe even more rewarding, by asking the basic question ‘what am I seeing?’

Ahead of his Paris show for Marian Goodman (12 February – 26 March 2022) Trebuchet interviewed Sietsema to discuss what processes of composition he utilised to realise old objects as symbolically aged.

How do you start?

Ha. I’m not a fan of starts! think I started many many years ago and it’s been a continuum since then-even with this first question-I couldn’t start with it. I went ahead and came back to the beginning to answer-too much pressure! I do remember when I decided to devote most of my time to making things in the 1990s- I really wanted to get going. I played a game where I’d have to make 3 things each day. Regardless of how bad the idea or lame it looked-I had to finish three things. Could be a simple nearly invisible public performance, a video, a sculpture, or a photograph etc. I felt like I was starting an engine-it needed to run for a while to warm up. But I also of course wanted to find out what my relationship was to this mess of things.

Is there a ‘click’ where you start thinking about a creative idea in serious terms. Have you learnt to recognise that point and what is it?

I see making things as part of the continuum, I don’t think there needs to be anything serious about art-and it’s not that I’m not a serious person-I just don’t give much weight to ‘good’ ideas. I do get a rush though if something is coming together in a way that emanates a quality I’m interested in. I would be so happy if something as finite as a click did happen and I could believe in that and trust it. But finding the right tone in relation to a world marketing aesthetics to us in so many ways all the time is what interests me most. And sometimes this means using the thing that doesn’t click.

Where does exploration fit into your method?

There is exploration to clear and refresh generally-and then I suppose exploration as a search for a new form, gesture, or moment. I think these two types of exploration are strongly linked-essential to each other. I used to search far and wide for inspiration and leads-but now I like the idea of these growing out of local situations. There is so much unknown about the things that are close to us, and of course anything can become a language.

When do you know you’ve captured what you want to express?

It amazes me that even after making things for so long I can still have a strong reaction to my own work. This helps keep me going-but of course I am a very small audience with very specific interests! There are chemical highs that accompany a moment of recognition-endorphins perhaps-it makes you hope the same bodily reaction is possible for people experiencing the work.

What stages do you go through to complete your work? What defines these stages?

There certainly are stages-accompanied by moods. I was trying just now to untangle my thoughts to write down a sort of concrete list of what I do. But as I try to do this I realize there are endings, beginnings, middles, etc, all stacked up on one another. In one given moment I am usually working on all (or almost all) stages of the process across multiple things. I may have started working this way to help keep me from letting my art fall into what I see as a design process; too much structure, too much order, too much intention would rid the process of what I find most interesting about it. I am most excited when I am starting something new-whether it is one piece or a show-the potential and unknown path ahead is at this point almost pure thought-intoxicating-and in my case this transforms slowly into labor. The movement of the hands is closely tied to the brain-and this helps the ‘thinking’ along in ways attention could never do. The thinking wrestling with form, and then the two becoming one at some point-inextricable and indistinguishable-is one of the nicest moments. Even more so because by the time this moment arrives the possibility of it happening or not happening is long forgotten. I used to think that the highest point one could reach would be to produce something that would be as natural in the world as a broom. As unexciting as this perhaps is-the idea of an unconscious construction (the broom) and a conscious one (art) having the same strength of existence in the world I think remains a goal.

Are these stages internal (from one feeling to another; exploration, challenge, doubt, resolution, conclusion, release) or external (idea, template, format, blueprint, mock up, draft, production, conclusion, package, release, sale, reporting)

The stages are absolutely both! So much handwork and so much thought.

What role does chance play in the process?

I’ve come to believe that both ideas and planning are restrictions that are unproductive for what I do. Ideas, the evaluation of ideas, often involves judgment of a type that can reinforce a status quo. The same is true of plans. And while of course these two are somewhat important for the more mundane aspects of life-for me they are not to be valued as tools of creative engagement. I do think chance (or something like it) is important for wider-more open communication, and also to be led somewhere new you wouldn’t have otherwise come up with.

How has your process changed over the years?

It is a strange feeling when you realize much of the hard won creative work you’ve done has opened up a new line inside you. It becomes internalized to a degree-which I think can be feel both dangerous (does one consciously need to steer the ship or is the autopilot you’ve developed just as good or better?) but also incredible-you can feel there is energy connected to this new line that is exercising itself in an almost independent way.

How essential is your understanding of your own process to your method of creation?

I do keep an eye on how I work I suppose-and I do find it important for the component parts of the process to be common and accessible things and methods-even if that is not apparent in the work externally-I always try to avoid specialization and methods that are out of reach because of skill or cost or technology. I think this locality and also wanting a chain of activity that is constructed based on my interests and understanding of working methods in the world-processes chosen for what they emanate or interrogate or symbolize-are both important aspects that work together.

Does a successful artistic process equal a successful result? And is this dangerous?

I think art has the luxury of existing in so many different forms, and along so many points of a process, and relating in so many ways to its maker that where the center of gravity is along this continuum for a particular piece changes immensely. With abstract expressionism in the last century it was all about process; splashing paint around in allegiance to the subconscious, the primal, the existential, for the most part-but of course the finished products now emanate a kind of extreme formalism and object quality that tries to make the colour and composition and material primary. With the conceptual artists of the 1970s for many it was all about the idea and the physical form of the piece was to be ignored. Like the abstract expressionist works many of the conceptual artists physical productions end up also having quite a physical presence-becoming successful over time as a kind of formalism, valued for its object quality. I suppose I think the two are so closely linked that they can’t really be separated, especially in light of all the other forces acting on an artwork?

Does a successful artistic process equal a satisfying journey? And is this dangerous?

I think many artists don’t choose their processes as much as they are chosen by…

Read more in Trebuchet 11: Process

Featuring: Samuel Andreyev / Ed Atkins/ Nairy Baghramian / Phyllida Barlow / Peter Van Dyck / Oli Kellett / Tae Kim / Chris Levine / Gisela McDaniel / Paul Sietsema / Jeff Muhs

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle