[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]C[/dropcap]huu Wai Nyein arrived on the Myanma art scene last year with the exhibition Synonym of Self, a series of paintings that were seen as daring in her native Myanmar for their portrayal of female sexuality. She followed this up with the exhibitions Vérités Alternatives and One Ten Hundred in the capital and this year made her international debut in Paris with the show Our Turn Now.

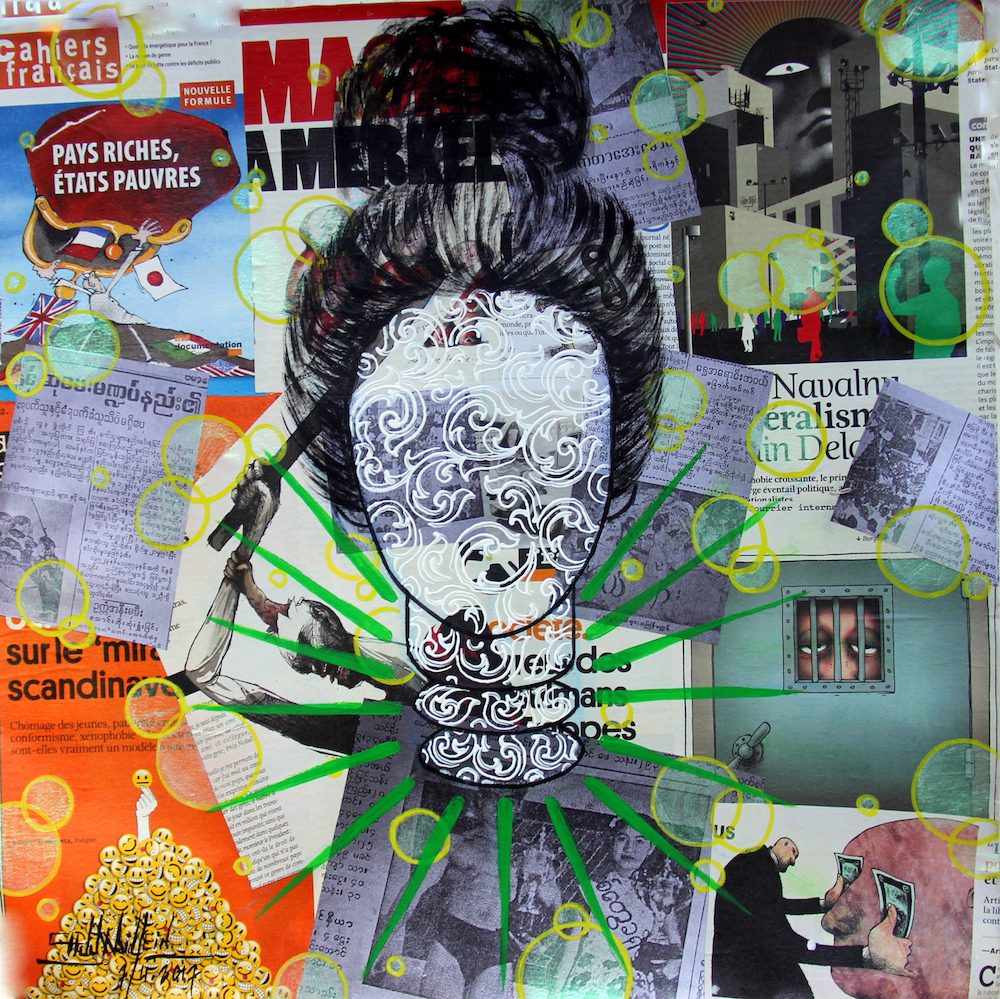

Much of Chuu Wai Nyein’s artwork is concerned with portraying the feminine as a plural phenomenon. Her paintings show vibrant images of sensuality and independence that are often juxtaposed with muted depictions and metaphors of restriction. A key series in Synonym of Self showed the faces of Burmese women, their hair tied up tight in formal buns, masked by sheets of beautifully embroidered traditional fabric. The message is clear and the effect, erasing the women’s features with patterns of gold and silver curls, is ghostly and uncanny. Yet there are other images that reflect an alternative vision of womanhood, full-body outlines of women striking sensuous and erotic poses gazing at the viewer in teasing expressions. It was one thing to portray women as victims of culture, but to show them as unashamed sexual beings drew controversy in a country where attitudes to gender remain strongly conservative.

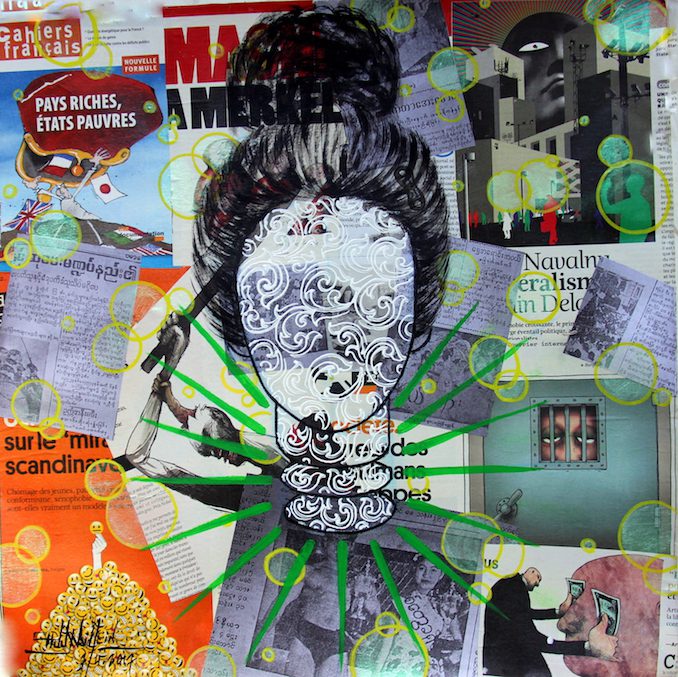

Her next exhibition, Vérités Alternatives, used French and Burmese newspaper as a background for a continued exploration of female identity in different cultures. This was followed by One Ten Hundred, a series of paintings which questioned received wisdom about history and tradition. Maids of the 19th century Yadanarpon Court have always been portrayed as the embodiment of traditional Burmese femininity but through historical research Chuu Wai Nyein was able to discover that the lives of these women were more intricate and full than the schoolbook representations that seemed to confirm patriarchal ideals. Her paintings thus offer an alternative glimpse back in time, and depict these feminine icons with a vibrancy and spirit closer to the truth.

Her most recent exhibition, LIBÉRÉES: Reclaim Birmanes Identities, continued the dual themes of constraint and liberty. There were images of anonymous mannequin-like women painted onto Burmese patterned fabric and then masked by the same patterns. These were displayed alongside images of women unmasked and proud in their own bodies, staring at the visitors with defiant yet calm expressions. By presenting both the restricted and the liberated bodies, she confronted and surrounded the viewer with the reality that femininity is a plural phenomenon, that can be both proscribed and won.

- Bearer of Tradition (2018)

- Garden of History (2017)

- Hidden Identity (2017)

- Synonym of Self (2017)

When you were studying art, did you ever think that being a woman would hold you back, as there are so few female painters in Myanmar?

I don’t think being a female artist holds you back, but I think being a woman in Myanmar can hold back your thoughts. The culture is controlling women too much and it is quite difficult to think beyond the control to get something new. That’s why normally you can see that many Burmese women artists are painting mostly flowers, butterflies and beautiful landscapes. And I think that our education also means that male artists have a difficult time too in thinking up new things to paint.

A lot of your artwork is about representation of women. What are your thoughts on the representation of women in Myanmar?

In the art scene, many male artists paint women and when they paint, they paint the women from the last 40 or 50 years. Mostly what they paint shows the control of women by men and society. That why I decided that if I painted women, I would show more about women as women.

What is your inspiration as a painter?

One inspiration for me is Pagan murals. Myanmar has its own history and art periods and within these ages, Pagan was the most beautiful and creative time. They made colours by using natural things and the way they paint murals isn’t realistic but it came from how they felt inside. Even though they are simple they are very imaginative.

The inspiration for my subjects came from the moment when a man sexually harassed my sister. Since that time, I started becoming more interested in women’s lives in Myanmar and became more focused as I heard and saw more stories from my friends and girls around me. This made me want to paint women to show how I feel through paintings.

What is your preferred medium?

I prefer acrylic. It’s bright and so this helps me when I paint powerful strong women.

What has been the reaction to your work in Myanmar?

At first, even my mom didn’t like the paintings. We argued a lot because of what I painted. But now it’s okay after they understand the messages behind the pictures. Most men don’t like what I paint, but some women send me messages and encourage me because they have the same feelings and have experienced the same situations. But some people think that I’m destroying the culture by painting these sexy Burmese ladies when they don’t know about the concept behind them. I got shock and attention in the beginning, and there are still a lot of people against me, but more are starting to understand me now I think.

Could you tell me a little more about how the royal maids of Yadanarpon influenced your work?

When I started painting women, I couldn’t paint women like I’m painting now. I had feelings but I couldn’t express them. I found a copy of the Yadanarpon maids’ images and they were my very first step in painting women. I heard that there were more than 100 of the images originally, but I couldn’t find them at first. I was really happy to find the original parapike [book] at the library. There were 200 images of ladies and almost all had a name. They were the women who trained new girls at the palace how to behave and treat the royalty. I noticed the way they dressed topless with open blazers and smoked cigars. And I realised that the real tradition and the tradition in the people’s minds are different. I think people have made their own history criticising mostly women. I repainted these women combining abstract and colourful backgrounds, showing the differences between real and created history. I showed some of my first Yadanarpon ladies at my very first solo exhibition Speed in Mandalay.

What is the relationship between artists and galleries in Myanmar?

Mostly we don’t have paperwork; our work relationship depends on understanding each other. Compared to the number of artists, there are not many galleries in Yangon. In Mandalay [Chuu’s home city], we really need a good gallery. We have very few galleries, maybe four or five in total even though it’s the second biggest city in Myanmar. None of them are well organised and they look more like souvenir shops.

We need more galleries that will help Burmese artists to be able to keep going in their careers and get better and artists need to know their painting style and to choose the correct gallery to work with.

What are your plans for the future?

After I paint about women, I feel that I want to paint men. So, in the future, we’ll see men in my paintings too. I don’t want to limit my artwork to only women’s issues. But for the moment, women’s problems are happening around me so this gives me things I want to talk about with my art. Mostly I just feel the lives and things around me and I make art from it, so my work will come from whatever I will experience.

Ewan Cameron is a writer and teacher based in the UK and Myanmar.