[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]H[/dropcap]ow do you visualise a post-internet world?

The internet has become so intrinsic within the very fabric of modern society that post-internet is becoming increasingly synonymous with post-apocalyptic. The reliance of both small and large businesses on the network means a long-term internet crash would heavily harm the international market, most likely resulting in the collapse of the stock market. The lack of back-up systems in case of internet failure would create, at the very least, a temporary state of chaos and social reconstruction.

Although studies have shown shutting down of the internet for a few days can increase productivity, this fact relies on the ability to catch up on work that has been left behind once the connectivity returns. Although increasingly unlikely, cyberattacks from hackers or destruction caused by natural disasters could result on a long-term offline state. Some nations even have their own kill switches that would entirely block the internet as a method of precaution in the case of security-threatening cyberattacks.

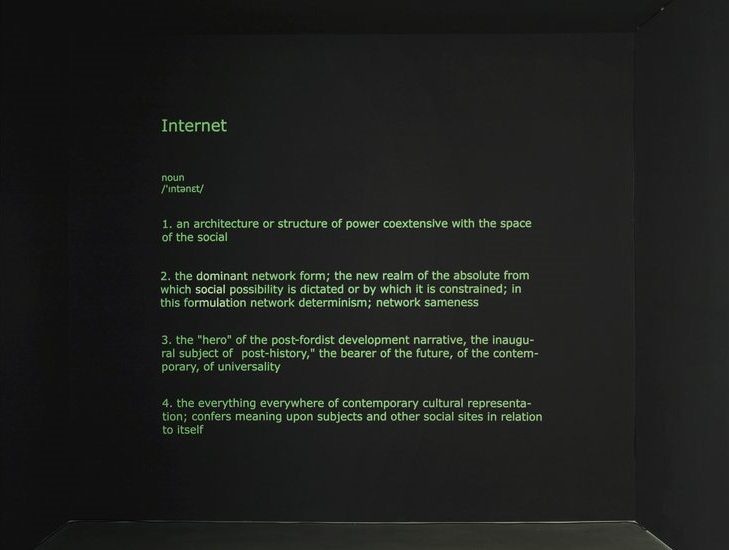

Zach Blas’ new exhibition Contra-Internet explores the issues and limitations created by this absolute infiltration of the internet in our lives, both in terms of our dependency on its continuing existence and our imprisonment due to its ability to regulate and control our behaviour. Blas breaks down the internet through alternate definitions, using complex words and fast-paced visuals which will without a doubt confuse and disorientate the viewer. Contra-Internet attempts to make sense of what the network means in relation to capitalism, surveillance, and hegemony.

Zach Blas, Contra-Internet, 2017. Installation view. Commissioned by Gasworks; Art in General, New York; and MU, Eindhoven. Courtesy of the artist. Photo Andy Keate.

Jubilee 1933, the central piece of the exhibition, is a strange cyber-psychedelic installation including a film in which a group goes on a LSD-fuelled trip into a post-internet world in which a group of students are taught by the entity Nootropix. Loosely based on the beginning of Derek Jarman’s 1978 queer punk film Jubilee, the film replaces the spirit guide Ariel with Azuma, a manga holographic character speaking in Japanese. The film directly references its predecessor in dialogue and composition yet becomes increasingly more absurdist as Nootropix, played by bodybuilder and performer Cassils, begins to dance.

Nootropix’s teachings fight against Ayn Rand’s philosophy of Objectivity, in which a man’s happiness works as his moral compass, thereby encouraging ethical egoism; a logical form of self-centric decision making.

The film-installation includes two blown glass sculptures, a single edition publication titled The End of the Internet (As We Knew it) on a podium next to a rock, and a glow in the dark vinyl sigil on the floor. The dark shrine-like set up of the glass sculptures on either side of the film in combination with the slightly glowing sigil create a slightly satanic environment.

The film requires more the one watch and becomes increasingly absorbing as it continues to play on loop. The smooth transition from ending to beginning makes the viewer loose track of its linear construction and begin to question the underlying logic of the narrative. This being said, Jubilee 2033 is a piece so contextually interconnected and reliant on knowledge of its supporting philosophical and popular concepts that understanding these references before experiencing the is installation essential. I would highly recommend watching the introduction of Derek Jarman’s film. Although the Zach Blas’ heavily researched theological background strengthens his work, it also makes it somewhat inaccessible and restricts the pieces from speaking for themselves.

Inversion Practice #1: Constituting an Outside (Utopian Plagiarism) is based on Ricardo Dominguez’s idea of utopian plagiarism. As part of the Critical Art Ensemble, Dominguez and his companions gathered concepts from books and came up with completely original although partially plagiarised concepts such as Electronic Pseudo-disobedience (from Thoreau’s Pseudo-disobedience). Zach Blas adopted this form of concept creation when he saw Paul Preciado’s contra-sexual manifesto lying next to his own post-internet poster in the Frieze magazine, resulting in the beginnings of the contra-internet idea.

Inversion Practice #1: Constituting an Outside (Utopian Plagiarism) is a screen recording film of Blas copying and pasting a series of extracts from texts by queer and feminist writers into a new document. The End of Capitalism As We Know It, for example, argues with the idea of capitalism as a totality, stating its existing alternatives in order to undermine it. Blas adapts such arguments by interchanging a series of words that transform the text into a contra-internet manifesto. Capitalism is exchanged for internet, non and anti for contra, economy and world for network, and so on.

The resulting manifesto explores the counter-progressive usage of the internet and encourages ‘a network decidedly more fair than the one which we now live’. This experiment, as I would define it, is fascinating in the way the final text makes total sense despite its contents having been completely altered, displaying an interesting take on the manipulability of language.

Inversion Practice #2: Social Media Exodus (Call and Response), also a screen-recording, shows us Zach Blas deleting himself from social media such as Instagram, Twitter, and his website, with the use of the Photoshop eraser tool. Although effective in its revolutionary statement of removing all evidence of his existence on the net, it is perhaps counteractive that in reality he is still active in all these forms of social media.

Inversion Practice #3: Modeling Paranodal Space, like Jubilee 1933 is extremely complex in the amount of background information that is not accessible through the artwork. Zach Blas takes Preciado’s idea of dildo tectonics as the alternative to normative sexuality. Preciado uses the dildo as a separate entity to the penis, displacing its normative use and allowing it to take an individual position used to undermine heterosexuality’s normativeness. Blas uses the paranode as the internet’s dildo, utilising it against the nodocentrist construction of the internet.

Zach Blas’s internet-resistant exhibition displays a thorough collection of theoretical alternates to combat the hegemony and control of the internet. Although difficult to fully grasp, Blas’s fast-paced visuals mirror the internet’s incomprehensibility and encourage us to approach it differently. The entire exhibition is manifesto not for the absolute destruction of the internet, but perhaps for its reconstruction into something better, as well as the removal of our perception of its existence as one totalitarian figure.

Until December 10th, 2017

Born in Barcelona and based in London, Anna writes about art, techno and psychogeography. She is also a lover of film photography and is slowly building an Olympus camera collection.