[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]W[/dropcap]e lament the dearth of counterpoint in contemporary music at the peril of being proved wrong.

It is a common moan amongst music critics – the simplicity of melody in contemporary pop, the over-reliance on chords and close harmonies. It’s a valid argument, but depends upon a rarified understanding of what counterpoint consists of.

Composer Michael Finnissy describes counterpoint with a clinical simplicity in an interview with Trebuchet’s Kailas Elmer: ‘I actually think contrapuntally, and that may not be all that different on the grander scale, but it implies working horizontally across the page, rather than vertically up and down the page’. There is a captivating, ineluctable beauty to the image that evokes the ‘fearful symmetry’ William Blake wrote of.

The description is interesting in that it asks us to think about music in spatial terms. Up, and across.

For those who imagine Johann Sebastian Bach sat at a two-keyboard organ, or Rick Wakeman stretching skywards between banks of synths, re-ordering a mental picture of counterpoint as a horizontal progession of notes is counter-intuitive. In essence though, that is what it is.

Trebuchet’s own Dave Graham expands on the concept , iterating that at its simplest, counterpoint is ‘when more than one melodic line is played – with some kind of contrast between the two’.

That makes thing interesting. It allows us to include the interplay between lead guitar and bass in, say, ‘Sweet Child o Mine’, and see it as something much more than a happy accident of axe-hero lick being followed by a hapless bassist hoping to keep up.

As an exercise in counterpoint the song’s intro is as sweet an example as a Bach fugue.

The same elements are there: a repeating treble figure, and the separate bass melody gaining steadily in complexity until the two merge. Iconic, beautiful, and a piece of quite complex composition that resonated so deeply with so many millions of people that a good chunk of them paid money to own a copy.

Most of the time we presume some repetition of the contrapuntal motif. A repeating figure, like Slash’s four-string melody on that Les Paul of his. A single note, followed by some harmonically related partner note (perhaps in a different octave), followed by another, etc. In the early days of computer games in the 1980s, musicians were forced into leaps of innovation when tasked with creating musical tension via the limited processing power of eight-bit machines. Multiple notes played as a chord were not possible, instead the right-brain/left-brain tickle of contrapuntal composition was brought into play. Bit-Hop and Grime continue that no-chords tradition.

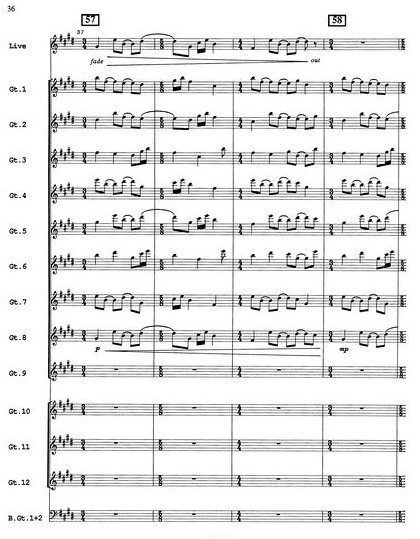

It all gets to be extra fun when the composer uses phasing. Having one of the melodic lines move slightly faster than the other, and gradually catching up as the piece is played through, effects a glorious dissonance on the listener’s brain. Dutch Uncles toyed with a now-famous passage of counterpoint for guitar in their song ‘X-O’. The intro and recurrent guitar motif is borrowed from Steve Reich‘s ‘Electric Counterpoint III (fast)’, although tweaked slightly to their own ends. :

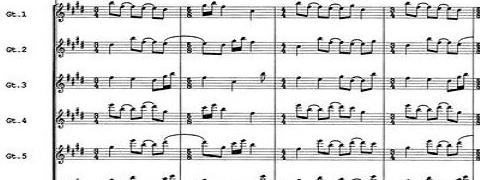

The original Reich piece is written for nine guitars playing (most of the time) simultaneously.

Complex stuff, but aesthetically satisfying regardless of the precision involved. Because the guitars are mostly playing within the same octave (there is only a sporadic bass line), it’s difficult to pick out discrete melodic figures, but they are there, repeated, layered.

Layering different sounds.

Layering different sounds.

Layering different sounds.

Savvy readers will recognise the midsection of the Reich composition, either as a piece in itself, or as the donor of the upper-mid sample that lends such otherworldly atmosphere to The Orb‘s ‘Little Fluffy Clouds’.

No castigation of either The Orb or Dutch Uncles should be implied from this. Musicians are always indebted to the composers who influenced them, and both acts have acknowledged Reich on multiple occasions. Nor should it be imagined that Steve Reich is without his influences.

[quote]whomping bass overdub[/quote]

Apart from anything else (drums, vocal samples, sundry boings and bleeps) The Orb attacked that aforementioned difficuty in discerning the individual treble figures, by adding a whomping bass overdub to twist in and out of the existing Reich pattern. Interesting, because it could have been a case of gilding a lily, but as countless tripping ravers found, it just added to the euphoria. That frontal lobe enjoys rich food, it seems.

Reich (along with Zappa, Nick Drake or Philip Glass) is a musician beloved by music snobs whose every conversational gambit includes reference to their rarified and erudite listening preferences. That is unfortunate, because there is little to be daunted by in Reich’s music – it is, if anything, an artistic reaction to events of our time that craves to be universal and populist.

Different Trains, a composition dedicated to examining the Holocaust, does not deserve to be sidelined by pseuds, nor does his WTC 9/11. That notwithstanding, it doesn’t help with the mini detective story to be built around that little passage of Electric Counterpoint.

So far, we have heard it, or a near approximation, in Dutch Uncles, The Orb, and in the original. A delightful phased contrapuntal motif for guitar.

But Reich has his own influences, and not all from the stuffy halls of academia either. Take a deep breath (or a solid hit of best bongsmoke) and listen for the genetic code of Electric Counterpoint in Terry Riley‘s ‘In C’ (especially around 6.00): a source of inspiration which Reich has also acknowledged.

Beyond Riley though, the trail becomes muddled, circumstantial. There is simply no merit in discussing counterpoint without invoking the name of its greatest master: Johann Sebastian Bach, but neither should we jump straight to Bach without giving honorable mention to Albert Schoenberg. Can we trace anything of the Electric Counterpoint motif in Schoenberg’s Suite for Piano?

Decidedly so, especially at 6.30 onwards, and if it doesn’t quite lead to Reich, there are definitely parallels with The Orb’s treatment of the motif in that dub bass melody.

If that’s too far to stretch, then perhaps a leapfrog to Bach might be more appropriate. Bach’s fugues are the example of the phased counterpoint par excellence, and, if we can listen through the difference in tempo, there is the germ of Electric Counterpoint once again in Fantasia in G major BWV 572. It may be a thoroughly muddied trail by now, but there is at least the ghost of a footprint to follow.

Further back than this we cannot go with any confidence. The choral descants of Allegri‘s Miserere may prove fertile ground for conjecture, or the call-response structure of monastic liturgy. The cyclical intertwining melodies of Indonesian gamelan orchestras display how a collective approach to composition can reap mind-blowing rewards.

We might, if we looked hard enough, trace Reich’s counterpoint to prehistory. There would be little point. Wherever we go though, even if only as far as Bach, it is significant that the use of counterpoint has its roots in religious ceremony. Softening up his congregation for Sunday church services, Bach was well aware of the mind-altering properties of the sublime, and induced it where he could. But beyond that, beyond the physiological effects, are philosophies.

World is suddener than we fancy it.

World is crazier and more of it than we think,

Incorrigibly plural

– Louis Macneice, Snow.

The development of counterpoint, the act of composing with the technique, of thinking in its twisted and interweaving way, acknowledges a world of experience outside and unconnected to the life of the composer. It is objective expression, an acceptance that existence is not a web which is woven outwards from the individual ego. Harmony or chorality cannot boast such sophistication or mental evolution.

A chord consists of many notes, but they are connected, and connecting. Counterpoint legitimizes the existence of the Other. Crowds at rugby matches do not sing contrapuntal descants.

And once you start thinking in those terms, it’s everywhere. Not just in music, but across the arts. Tarantino‘s weaving timelines in Pulp Fiction, Seurat‘s holistic visuals constructed from individual spots of pure colour (that never touch). It can become an obsession. In literature, all seems simple: events narrated over a period of time seem obviously horizontal in their progression, descriptions of sense or place can be thought of as horizontal.

Fine, Structuralist critics came up with that in the 1940s.

Which worked until they tried to apply the theory to moderist writers. Eliot‘s The Wasteland confounded the theorists, Joyce‘s Finnegans Wake destroyed the theory. Try deciding whether Joyce’s description of a river flowing belongs to a chronological narrative when a nine-word sentence contains five references to different characters, each of which symbolising at least three meta-narratives, those narratives themselves alluding to two central themes, and each of the words making puns on the motif of rivers.

But that is another essay. This one was about counterpoint in music. And the fact that it’s more prevalent than is sometimes thought. We think of it as being confined to masterpieces, whereas sometimes it happens in much less ambitious compositions.

And the truth of music in 2013 is that we don’t really need a masterpiece right now.

We need a higher grade of ordinary.

The London Sinfonietta will perform the world premiere of Radio Rewrite, Steve Reich’s new piece based on the music of Radiohead, at the Royal Festival Hall in London on 5 March. Further performances will take place at Birmingham Town Hall, 6 March; Brighton Dome, 7 March, Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, 9 March.

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.