Sound art, traditionally visual art’s poor relation, promises more now than other forms of creative activity. It’s a legacy of our privileging of sight that we haven’t considered the aural as offering a complete experience on its own. Sound installations require active engagement and this may be their salvation in a world where the passive consumption of visual media has led to diminishing returns artistically.

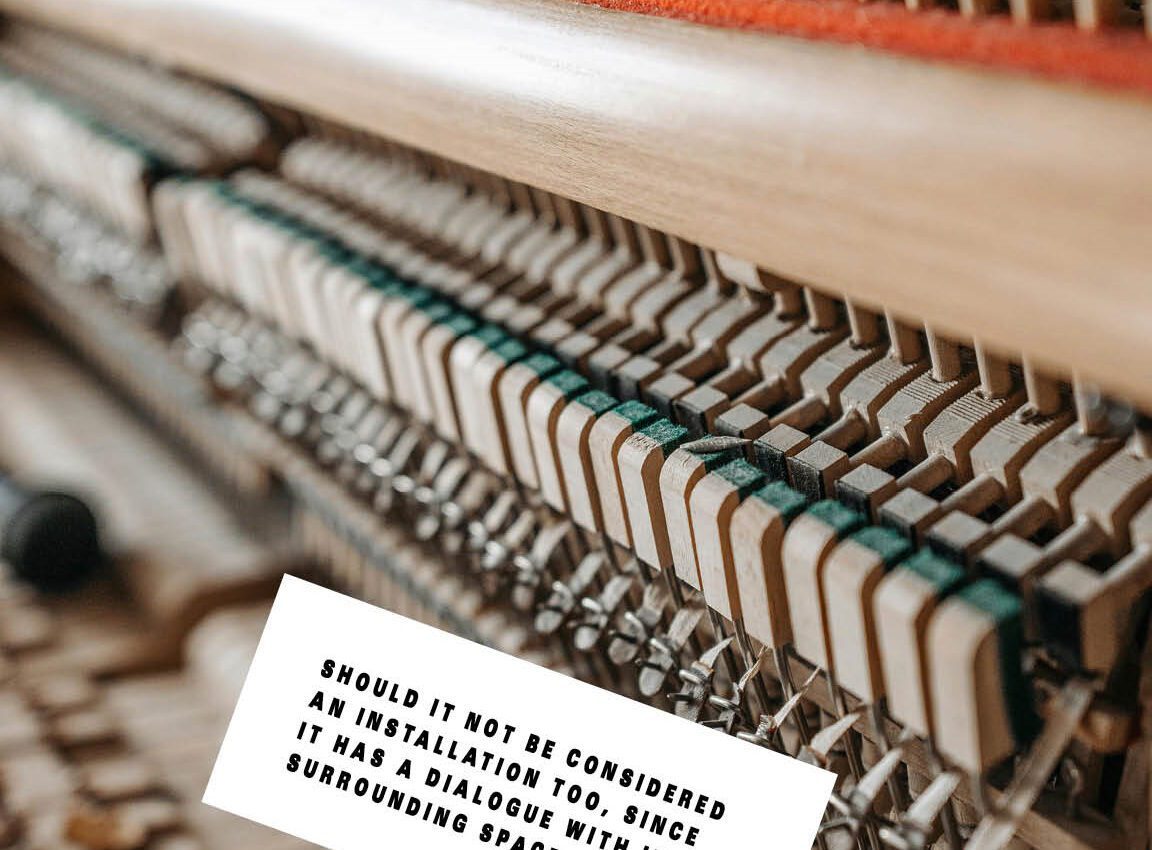

Although the first use of the noun ‘installation’ in a sculptural sense is cited by the Oxford English Dictionary as being in 1968—the Nelson Gallery of Art commissioned “environment installations”, which included light and sound—the practice has existed since the first cave dwelling. Now, because of the way it enables dialogue with a surrounding space as well as a time element, sound art is expanding the concept of installation in a way that can be both multisensory and novel.

By the late 1970s, Jacques Attali had already observed that technology would keep developing until everyone could make music. He identified four cultural stages in the history of music, each with their own mode of production. The first stage before 1500 covered music as an oral culture with elements of ritual use. The second stage, up until 1900, concerned the era of printed music and the emergence of specialist performers. Between 1900 and the 1970s recording technology replaced notation. A post-Repeating era was not clearly defined, but would have involved the plastic manipulation of tape as in musique concrète or Terry Riley’s “interactive real-time electronic music” (Carl 2009).

Sound installations undermine the single viewpoint of conventional visual art. This reflects the fact that the form was gaining prominence in a period of emerging critical theories including feminism (note the female artists finding expression in sound art installations). As they weren’t curated exhibitions in galleries, but artist-curated installations in non-traditional spaces, there was also an emphasis on listener participation (something else that has been demonstrated as future-proof for sound installations).

An archetypal example of sound art is Annea Lockwood’s Piano Transplants. Nothing declares itself avant-garde like the destruction of a piano. It speaks to our inherited prejudices that this instrument, so strongly associated with the classical Western tradition and all it stands for, should have a sledgehammer taken to it. Yet for Lockwood’s work, which includes a burning piano and a piano planted in a garden, it’s not about destruction. Instead, subverting late twentieth-century expectations, it encourages critical listening and reminds us of a constant unseen energy flow around us. As Duchamp elevated the ordinary—to which we have acquired a visual indifference—to objects of artistic contemplation simply by virtue of his making a choice, Lockwood is concerned with sounds that have become so common we no longer listen to them. The instructions for Southern Exposure (1982, realised 2005) are:

Chain a ship’s anchor to the back leg of a grand piano.

Set the piano at the high tide mark, lid raised.

Leave it there until it vanishes.

The sounds come from the way the piano is abandoned to the elemental process, until finally overwhelmed by nature.

Many are still schooled to regard such acts as vandalism, the products of an unhealthy society. Some might assume a protest they don’t understand. Others, the meaninglessness Brecht talked of being “welcomed as a means of liberation” (Brecht quoted in Hauptmann 1964). But is it liberation, and does it signal a deep forgotten health-giving connection? … (read the full article in Trebuchet 15)

Read more in

Trebuchet 15: Installation

Featuring:

Installations as theatre

Giuseppe Penone

Michael Landy

Annette Messager

Karolina Halatek

Sounds Art as Installation

Jean Boghossian

Jon Kipps

Chantal Meza

Musician and poet Neville studied under Seamus Heaney and now releases cultish music to international acclaim.