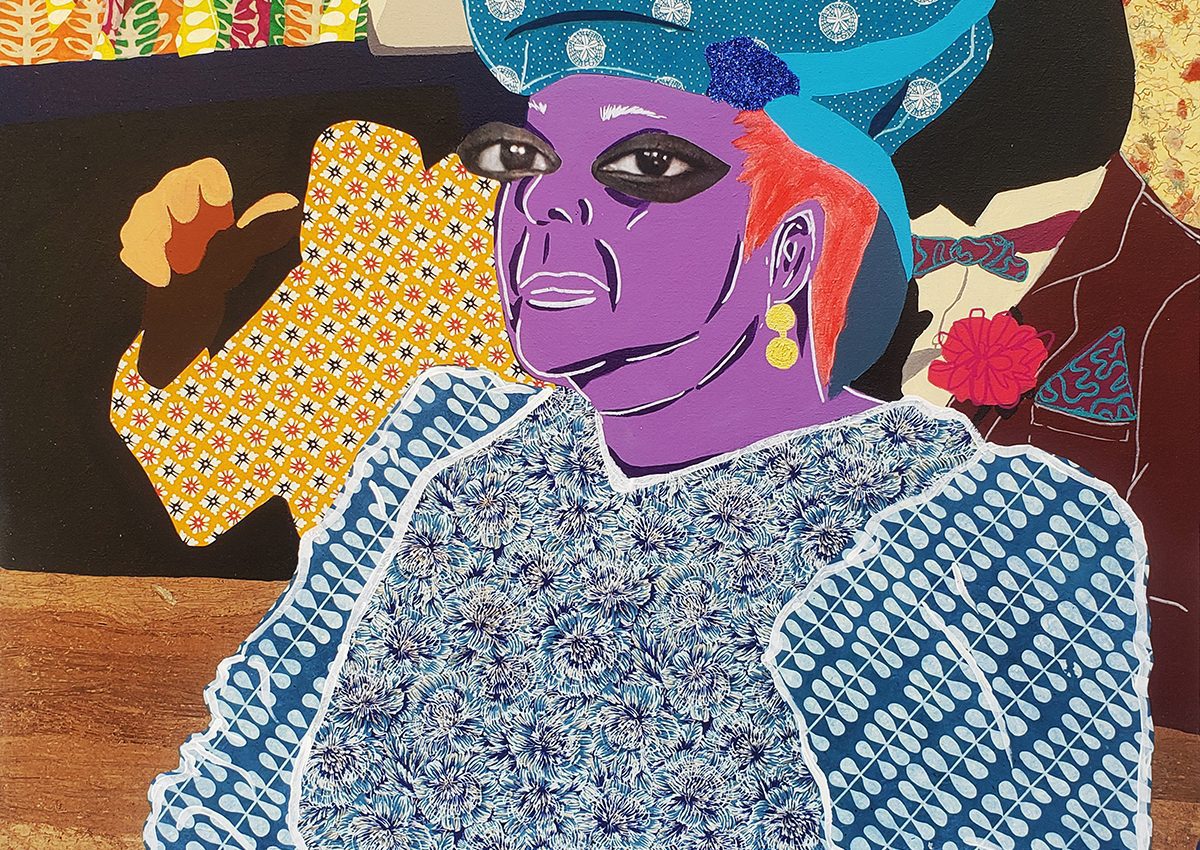

Bahamian artist Cydne Jasmin Coleby creates vibrant collage portraits that explore identity, heritage and notions of place, drawing on personal experiences and family histories.

For her first solo show in London, Coleby presents a new body of work that reimagines the matriarchs of her family, stitching together intimate archival imagery with bright colours and patterned fabrics in a powerful celebration of black women and life in the Caribbean.

Here, the artist discusses the tensions of self, art as a place of safety and finding truth through juxtapositions.

What appeals to you about the cut and paste processes of collage?

When I think about my practice and how I’m building upon experiences, identities, and ancestry, collage makes sense, thematically. The technique allows me to pull from an existing narrative and explore how that makes an imprint on another narrative. Whether I’m infusing a combination of experiences from a single person, or I am using a combination of experiences from multiple people and showcasing how those culminated in one body, collage is successful for articulating these thoughts.

There’s also a harsh abruptness to cutting and pasting, insinuating that this juxtaposition of ideas and entities isn’t necessarily seamless. There is this obsession that people have with seeing the refined clean-cut version of things, and that’s not necessarily how life, or humans are. There’s a lot of tension that can exist in a single identity, and this tension is honest and human. In showcasing my figures in this way, it’s not only a representation that I find to be honest, but it’s also one that celebrates this absence of refinement. It’s okay to not have it all together.

In their colours, patterns and textures, your images are often surreal. How does this relate to the wider explorations of your practice?

Though it would be atypical to see this concentration of colour, patterning and texture in day-to-day life, it’s not far-fetched. You would find this more commonly in celebratory settings like festivals, parades, weddings – any setting that’s meant to exude joy. My practice celebrates aspects of my life and my history, and I want to present these narratives in a jubilant way to the world.

Also, environments heavily inform colour palettes. Living in The Bahamas, for example. It is genuinely a vibrant place. We have literally been referred to as “the most beautiful place from space”. Daily, I walk outside and see bright leaves from trees vibrate against a crisp sky blue; or the jewel bougainvillea flowers glowing in the sunlight as though they’re backlit.

In the past, your practice has explored representations of self but your current exhibition draws on stories and imagery of the women in your family. What made you decide to change your focus? And how did you find the process of engaging with your ancestry?

In all honesty, my fascination with my heritage has been there since the beginning. When my practice resurfaced with my God called self series of works, the collaged figures in those pieces were comprised of images of myself as well as family members. At the time, I was examining how their life experiences shaped how they interacted with me, and as a result, how I viewed myself. It’s easier for me to show compassion for others than for myself, so by acknowledging the presence of my loved ones in my identity it makes the act of self love a bit easier.

From there, I started to experiment with images of my family as the subject matter. In a smaller body of work entitled Generational Curses, I use images of my parents and my siblings, stylising them and juxtaposing black and white images of myself as a way of more obviously expressing the linkage between us and how we influence each other.

After that, hurricane Dorian hit The Bahamas in September 2018. It was the worst recorded natural disaster to hit the island. There was extreme loss of life, not only in the literal sense of people that died but also in the loss of their archives. When you lose all records of a person, their legacy is destroyed and legacy is how we live beyond the grave in this life. When the hurricane hit I was in New York City and I was scheduled to return around the same time that the hurricane was over the islands, so my stay got extended. Because of the extension, I was able to visit my Grand Uncle Newton who I hadn’t seen in years. He acts as our family historian and he reacquainted me with so many family photos and documents. This was when decided I wanted to spend time preserving this history, my history, the best way I knew how.

A few years prior to all of this, I lost quite a few close family members in a short period of time. As a result I shut down emotionally, and actively avoid engaging with family more than absolutely necessary. For me, it just felt like a futile act, and I was trying to protect myself from inevitable pain. The weaker the connection, the easier the break. Art has always been a safe space for me. Making these works has been a way for me to gradually reengage with my family and myself.

To me, there seems to be a tension between beauty and the grotesque in your latest works (the vibrancy of colours and patterns versus the distortion or occasional absence of facial features). How does this reflect your ideas around black female identity, and trauma?

I have honestly questioned if the the ways I’ve portrayed black women in my works was too unflattering and if it reinforced racist ideologies. Ultimately, I found that I was trying to avoid perpetuating stereotypes and standards that were too rigid, and denied my subjects aspects of their humanity.

In an effort to negate these vilified notions of being, black women feel can pressured into unhealthily overachieving and policing their flaws. Personally, I have also have had battles with perfectionism. Even here in the Bahamas where the population is majority black, I still have to navigate colourism (a subset of racism) and misogyny. I still consumed mostly American media (television, magazines, etc.) so I internalise that outside of my home – I wasn’t necessarily an example what the world would “aspire” to. These consistent assaults on my identity led to me to feel that I had to constantly validate myself and prove my worth. All of which led me to want to give grace to my imperfections as well as black femininity at large. To be flawed is to be human, and I find that wearing our humanity boldly is one of the best things that can be done to uplift the world perception of black women.

This is not to discredit the artists who chose to showcase black femmes in a picturesque way. That is equally as important to the conversation about the black female identity, because it’s true: we are picturesque. My work simply offers another element to the conversation; multiple truths can exist at once.

The fabrics, in particular, add a distinct tactile quality to the works that seems to express the physicality and sensuality of the body. Why is this important, and how do you select the materials that you use?

Selecting materials is almost like trying to find pieces for a puzzle. My process is completely digital in the beginning. I sketch out my works entirely using technology and I know almost exactly what the work going to look like before I touch the canvas. Once I have the composition figured out, I add the textures and patterns in photoshop. My goal is to create something that is not only aesthetically balanced, but fits the preexisting forms and evokes a particular energy. Especially in my self portraits I used texture to build the figure. For example, I would look for textures or patterns that mimic physicality (e.g musculature), bulbous forms that imply a metastasised tension, or literal sand or images of coral that indicate the roughness to show show the depth and how it culminates into a recognisable being, even if that figure is unconventional.

Can you talk to me a bit about the theatricality or performative aspect of your works? It’s interesting, for example, that your figures are often depicted facing the viewer, as if consciously arranged for the gaze.

You’re right! My work has showcased highly personal and intimate scenes, and a lot of people of asked me how am I so comfortable with being this publicly vulnerable. Having my eyes in the works meet the viewer’s gaze is a way of addressing this vulnerability. As I’m exploring the relationships with the people in my work, I want the viewer to know that I see them looking in this moment – similar to when you meet a strangers gaze after watching them for while. This exchange can be intimidating, aggressive, inviting, or alluring.

How do you think your practice engages with or disrupts notions of place and in particular, perceptions of the Caribbean?

Well, it depends on which perceptions we’re looking at. If we’re talking about the world “travel destination” narrative of what the Caribbean is, then my work disrupts it. When talking about the Caribbean as a vacation spot, the conversation centres around the visitor and is usually void of whatever doesn’t include their enjoyment in those spaces. My practice centres Caribbean people in a way that’s not necessarily catering to the viewer.

The referral of the Caribbean as a “paradise” erases the life experiences of Caribbean people. The Caribbean is more complex than a picturesque haven for travellers to escape to. It is true that this place is aesthetically beautiful and vibrant, and my work engages with that, but it also presents images of my home and people that aren’t traditionally broadcast to the world. I find that there’s more truth in the juxtaposition.

Do you see your work fitting into the wider contemporary art scene in The Bahamas?

Most definitely. I feel honoured to be a contemporary to so many talented and thoughtful artists here in the Bahamas, most of which are women. In the past, there was a local argument that The Bahamas was “losing its culture” due to modernisation and American influences based on our media consumption and physical proximity. There is a section of contemporary Bahamian art that is a rebuttal to this argument. These artists validate aspects of our heritage in thoughtful ways, exploring the personal and societal evolution of what is understood about being Bahamian. I think my work fits within space.

There are few spaces I would tell people to check out if they want to know more about the contemporary art scene here in The Bahamas such as The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas, Tern Gallery, and The Current Gallery and Art Center. And if they want to follow Bahamian artists directly, I’m a huge fan of Tamika Galanis, Averia Wright, April Bey, Drew Weech, Tessa Whitehead, Jodi Minnis, Gio Swaby, Kachelle Knowles, Leanne Russell…. The list could go on and on, but those are the people that come to mind immediately

Are there any artists that have been particularly influential to your practice?

When I look at my work, I see my love for Mickalene Thomas, Wangechi Mutu, and Romare Bearden shine through. I also have to give homage to a few Bahamian artists here who helped guide me through and to my practice as I know it such as John Cox, Maxwell Taylor, Sonia Isaacs and most recently, John Beadle. Beadle doesn’t know it yet, but I’ve adopted him as a mentor. And finally my work exists alongside Bahamian artisans and craftsmen, like Junkanoo artists and straw weavers.

What are you currently working on?

A few things! I’m going to be a part of my first museum showing in June – a group show curated by Melanie Lum at the Asia Art Center in Taipei. I’m also working towards a solo showing with Galerie Julien Cadet in December. In between these showings, I’m going to completing a list commissions that were booked a few months ago.

There has been a strong interest in my work which I’m really happy about, and to those people I say be sure to look out for the limited edition releases I have this year. Recently I released a set of limited edition Vases that I designed with Maria Brito exclusively for SHOWFIELDS. And I have a limited print release that launching in the summer with UNIT Drops. I’m a busy woman, and I couldn’t be more grateful.

‘Cydne Jasmin Coleby: Queen Mudda’ runs until 24 April 2021 at Unit London, Hanover Square. For more information, visit: unitlondon.com

Featured Image: Church Mudda, 2021, Cydne Jasmin Coleby. Courtesy the artist and Unit London.

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.