[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]

here are moments, in a middle-aged man’s life, when an ordinarily diffuse misgiving comes sharply into focus, forcing a pause and reminding him how quickly life changes.

It passes. Maybe it’s comparable to looking back down a half-climbed mountain and being astonished at how far one has come. But when I experience it, I see more clearly each time that within this general misgiving lies an explanation for something, if only it can be properly sketched out.

Communication Between Worlds

An explanation for what? That is harder to say, and even then, may take a while. On the latest occasion when this hesitation materialised, a confluence of factors seemed to impress upon my consciousness, leading me to stitch together large political and social narratives with the more parochial details of my own life. And it casts David Bowie in the role of thread.

I remember my school when I was a young boy of about five. I have dim memories of a kindergarten before that, and a friend called Gavin who had a peculiar skin tag hanging from his left earlobe. We used to crawl under the stacks of chairs and hide from indifferent teachers.

School though, was an altogether more serious affair. Every morning the tannoy would play ‘O Canada’ while we all stood behind our desks. Then we might sit in small groups and read. Or rather, I would read (as I was the only child who could read, my mother having taken the trouble to teach me). Then we might run around in the playground. I seem to recall earnestly digging for fossils on an old mound of dirt, and a tough kid called Ross who would entertain us all regularly with his fighting prowess. I do not remember any homework.

The school was only a few hundred feet from my split-level, ranch style home on 4th Street East, Fort Frances, Ontario, and I was old enough to walk home by myself, where I might watch TV, or find other creative ways to avoid my siblings. Once I watched a film that involved monsters and quicksand which gave me nightmares for years, although I recall very little of the detail, save a kind of space suit and either extreme cold or heat in a sort of grotto that was concealed by something like a hedge.

The TV was black and white, and very small, so perhaps I misunderstood what was going on even at the time. My mother would come home after work to cook supper and threaten us with the wooden spoon until we shuffled off reluctantly to bed. Then my father would arrive home once we were safely out of the way, to walk the angry, hateful dog which was ordinarily chained up outside the garage and that we all loved, apparently.

I haven’t thought about any of this for years, but somehow my own five year old daughter’s homework dredged a few things up. Her school is several miles away, across Victoria harbour, in deepest Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong. Her mother takes her there in the morning, before going on to work. I meet her coming off the bus in the afternoon, give her a snack, and coach her through her homework.

First comes her Chinese writing, then maths and reasoning exercises. Then some evenings she will sort English words in order of sounds, before going on to do more maths exercises on a dedicated website where her teacher can see her results. Then she will have supper and a bath, after which she can watch a bit of age-appropriate TV. As bedtime approaches she will read a short book, one of three or four a week that comprise her reading homework.

Last night, she needed to prepare for an upcoming class performance in which she will sing songs from The Lion King. In order to help with this, the school provided links to YouTube videos in which the songs appeared.

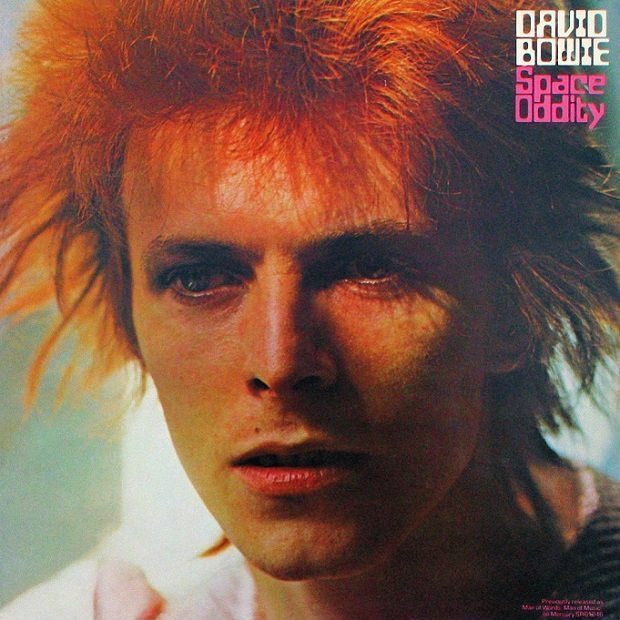

Then I had an idea. I would show her some music videos that I remembered watching as a boy. So I showed her Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’, which I watched on Top of the Pops (after my family and I moved to England )— when I was about seven or eight. She was delighted. I moved on to David Bowie. We watched a few of his old videos: ‘Fashion’, ‘Heroes’, and the bizarre chiaroscuro of ‘Ashes to Ashes’, but the one that really caught her attention was, of course, ‘Space Oddity’.

Whereupon it all came flooding back. The unreality, the strangeness I had experienced when I had first seen this same video, decades ago. And like Proust’s madeleine, it summoned up an entire world of meaning, which, although I can relate to it very directly, I nevertheless find very difficult to elaborate. So much has changed.

The video was one I remembered clearly, although it actually dates from just before I was born. It shows a young Bowie with English snaggle-teeth dressed in tight clothing and role-playing the actions of an astronaut, at one point lowering a blue visor over his face, then slowly walking through a studio door into a sort of blackness. It’s not very good by today’s standards, but it was mesmerising, in a way. Bowie has that characteristic look that hovers between the 60’s and 70’s, longish bobbed hair, fresh skin, wire-framed glasses and a hint of decadence in his ever young eyes.

I tried explaining to my daughter what a music video was, and how particular they were as set-pieces, but in a world of constant, unending collage, where images and sounds form an unbroken existential relief, my vocabulary was not quite up to it. My attempt to make her see how this song was about an astronaut being slowly seduced into the abyss was perhaps a bit ambitious, but even attempting to convey the sheer captivating awe of space exploration (having lived close to the period when it really was new and utterly staggering) was difficult.

The curious thing was that in attempting to describe all this, this mood, this moment, I caught hold of something that I have been merely grasping at, for years. Standing in a lecture hall trying to convey to people born after the fall of the Berlin Wall the stark horror of nuclear annihilation, which formed the backdrop to my vulnerable teenage years. Even trying to explain what it felt like to see those masses of people turning on Ceausescu. Blank stares. You live your life in crashing waves, but it translates as flat sea.

And as I look upon my sweet five year old daughter, I realise that I don’t know how to convey to her the very things I want her to know, to understand. She will always see things through a frame that has a different gradient of exclusion and inclusion from my own. My early years were all outdoors, running in the streets with gangs of nameless children, dodging the troubled, confusing Ukrainian neighbours who still nursed nightmares from the Eastern front. Them and the dogs and the bears. My move to England from Canada was like stepping into a dilapidated mansion as it geared up for the angry flourish of Thatcherite renovation. Necessary, redemptive, but like major surgery, from which the UK still struggles to recover.

How little we knew then, and yet how much has been forgotten. And this world, this world where my daughter grows up. It is so utterly different from the one in which I grew up, just as my world was so different from my Father’s. I think back over the stories he told me, about wartime and the aftermath. About the loss of his mother to cancer when he was 12. About his struggle to make ends meet. About his decision to emigrate to Canada and repopulate the dying empire; by which he meant me, I suppose. About all his crashing waves that until now I have only seen as flat sea.

And I think of my mother, with the loss of her father — his great medical mind shattered by war and alcohol — at the tender age of 19, and I see a glimpse of what they did. Drew together frayed edges and tied them fast to a family. I suspect they have few real regrets. Not none, but few.

Where was I? Oh yes. That intoxicating madeleine. My daughter; what will she know of my world, she that only — so far — knows my world? Not much, I suspect. She will know what I know. She will know what I tell her. But she will not know, until she wants to know, exactly how a life proceeds. How its beginning connects to its — still hopefully long deferred — end.

She will need another’s help for that. So back to David Bowie. She drew a picture of him in his Ziggy Stardust period. Then wrote things on the back of the picture about his different coloured eyes, that he was the best singer in the world, and that he was sometimes called the ‘thin whyt gook’.

That required a conversation, especially in Hong Kong.

I think I had a little victory, somehow. Opened a door, just a crack, in the hope that one day she will see past her everyday experience of once-unimaginable material comforts, of cultural and multi-media saturation and her complete exposure to the highly distinctive worlds and inter-worlds between Anglo-America and China that are both open to h er as they never will be for me.

er as they never will be for me.

She will hopefully see that the world does not simply contain billions of other people to whom she is more or less connected, but also that she bears a legacy, that her birth was not an accident but a consequence of past lives and past intentions, along with long forgotten mistakes and a measure of coincidence.

Two weeks ago I listened to a short lecture on the Battle for Hong Kong, which took place when Imperial Japanese forces invaded the colony in December 1941. Before the invasion took place, Imperial defence chiefs conceded Hong Kong could not be defended, although it was necessary to try. Seeing photographs of some of the personnel and recognising various landmarks obliged a realisation that history really was not so very long ago.

And then I think back to that problem of transmission, of how to bridge the generation gap and make my world comprehensible to my daughter, when her world is already filled with infinite layers of meaning. And more widely, how to encourage young people to step outside of themselves and see the wider context of their lives, by which I mean not simply as a category of being, but as a link in a chain. With this I think back to those moments of absolute incomprehensibility that seemed to decorate my adolescence, and in which David Bowie offered me an esoteric signpost.

Hong Kong is very different now, from then. It has gone from an outpost of Imperial pomp, to a nexus of mercantile intersections. From flags and ceremonies, to skyscrapers and globalised anonymity. But the real evolution has been mostly cosmetic. Much the same thing happens here as before. Much the same kind of people live here. For all the changes, Hong Kong has been a sort of constant. The British Empire has dissolved, the Japanese are pacifists, America is in retreat and the downtrodden Chinese are the rising masters.

Hong Kong, though, is still semi-detached, falling and rising with the tides of power. A comfortable place to live, a promising place in which to grow up. A window on both East and West, as much as on the future, and the past.

From here I look back to that small town in Ontario where I was born, and from there to wartime London where my parents inherited their task of gathering shattered, wartime fragments and assembling something new. And although my daughter was not born here, this is where she will learn about the world. Hong Kong will mean to her what Canada has always meant to me; a beginning. And with these generational steps I can sketch out a path into the deeper past, making a kind of sense along the way.

This path stretches back hundreds of years, along which the 20th Century looks like a deviation, an aberration, even an anomaly. And it is a path along which people mostly faced forwards to the next step rather than inwards on themselves. When change is rare, people grasp at it when it comes, but when it is ever present, they struggle to hold on to themselves.

The maelstrom of industrialisation threw my ancestors from their rural timelessness, and boiled them into the sinews of an entire world system. But because they were among the first, they now carry the blame for many ills now obvious to a world newly attuned to the sort of suffering towards which everyone had been hitherto indifferent. History is hard, and hard times raised hard people, but ignored their softening hearts.

The First World War exploded like Krakatoa on a world that did not understand what it was stumbling in to. The aftermath made the rest of the 20th Century inevitable. The dreadful wars, the desired extinctions, and most of all, the rise of a new way of seeing, and therefore thinking, in which we are all alike. Or, not quite alike, but equal, on some level at least. At the very least.

The Second World War — really the final act of the First — which wrought such damage to my family, saw the retreat of the ‘Great’ in Britain. We ‘won’ and fought like devils, but had no stomach for the aftermath. In any case, the empire disappeared. As much because it rose up and insisted as because we had become kind. And slowly, through the 50’s and 60’s, British people woke up, gradually throwing off the hazy, soporific dream of greatness. My father left for Canada.

But something was not quite right. Something about the 50’s and 60’s that too willingly embraced the new. There was a British space program, Quatermass, and Doctor Who. Drugs and sexual freedom. The promulgation of excess. Eventually David Bowie — casting his acerbic, philosophical skepticism upon the bracing possibilities for mankind — threw open the 70’s.

This was the smoke and alcohol of last night’s party. Then the hangover and the second thoughts. Not about everything of course, but a realisation that not everything had changed, nor did we really want it to. There was a clear-out, obscured by the headline disaster of long deferred de-industrialisation. Old rules, old conventions were swept aside. Charles married Diana in the most televised anachronism in history, then things started to fall apart.

This is the backdrop to an ongoing series of generational impasses. It made my father’s world quite distinct from my own, and will make my daughter’s world different again. And it is a feature of social evolution that big changes, political, historical and technological, generate radical mis-steps and discontinuities, leaving whole generations stranded. It is, on reflection, not so surprising that World War might shred the threads of continuity.

Nor should we see this as unique to our world. It must be true of the 1830’s and and 40’s that the preceding period of revolution and war had left its mark on the habits of the day. It also sets in a different context the knowledge that my stern old Grandfather had a motorbike as a young man, had lost his older brother at Ypres, and took a dim view of his sister’s lurch toward the 1920’s demi-monde. It throws new light on the fact that his wife — my Grandmother — had lost both her parents as a teenager and had to muck in with her Aunt and cousins to make ends meet. It breathes life into an old story, of which I am merely the latest chapter.

It is sometimes said that to build a new temple, one must first destroy the old one. It is rarely remembered that even in the idea of a new temple, reside traces of the old. The twentieth century swept much away, but the footings of something permanent remain. Over the course this period, it has seemed like each generation has gone out of its way to detach itself from the last, to reduce the past from a lived experience into a kind of formula or a set of bullet points.

I could follow the trend, sit back and see what sense my daughter makes of it all. But I think then that I would fail somehow. That my task is to let her know how she came about, to haul her up from the flat horizon span in which she is taught to see herself as merely one among 7 billion, so that she can see further. To encourage her to look down that mountain, and see how far she has come, how far all of her ancestors have carried her and which route they took, then help her to look up to see how far there is still to go.

But most of all to know that as she makes each slow step onwards, she — like everyone else — carries countless hopes.

By this means I aim to do my small part to gather still frayed edges and bind them more closely. Replenishing that common thread with new life and restoring its continuity through the fractured disharmonies of the twentieth century back to the more distant past.

Along with David Bowie, and perhaps in part because of him, I spent much time reading Science Fiction as a boy. It was a point of disagreement with my Father who thought it was all worthless, preferring Sherlock Holmes and anything by Buchan. So my adventures in space-time went unaccompanied. I dispensed with the more fantastical and settled on Arthur C. Clark and Isaac Asimov, two displaced pioneers who left their own countries behind. By some cosmic coincidence I even attended Arthur C. Clark’s old school in Taunton for two unhappy years.

Science Fiction drew me towards philosophy, in the way that contemplation of such enormous distances must, and after much searching, I found the questions of existence best expressed in the works of Philip K. Dick and in the films of Andrei Tarkovsky. Now though, those visionaries have a challenger.

In a way that would have been impossible even just a few years ago, I recently switched on my cable service that attaches to my 55″ flat-screen TV, and browsed the films they had on offer. Without any advance awareness, I thought I would try a film called Interstellar, directed by Christopher Nolan and written by his brother Jonathan. Both of these two are described as English-American, coming from that same hybrid diaspora from which I spring, both even attending an English public school similar to my own. They are my kinsmen in some respect, or so it feels. The story concerns a rescue effort, a dying planet, wormholes and time travel. It also draws upon plausible theoretical physics.

It is, dare I say it, a masterpiece. Not only are its visual and dramatic portrayals of space travel truly breathtaking, but the story thread revolves around a father and a daughter, his need to leave her behind as a young girl, but yet the necessity of reconnecting with her across time to transmit knowledge crucial for the survival of planet Earth and, ultimately, the human race.

Perhaps it is a coincidence, but rarely have I felt so close to the inner meaning of a film. Then seeing David Bowie in the news again brought the whole train of thought, that lifelong misgiving, into focus. I am instantly reconnected with the sad and lonely teenager that all those years ago felt transfixed by ‘Space Oddity’, by the dilemma of Major Tom, ‘stepping through the door’, meeting nothingness head on, only to die because of its indifference.

I can feel, once again, flowing through my veins that yearning for meaning that I, and so many others, identified with back then. And it all becomes staggeringly clear.

We live in flat times. But we did not get here by accident. Somewhere, somehow, animals started using tools, tools made better animals, those animals became philosophers and artists, giving meaning to blank physics. History intervened and at moments of deep peril the whole endeavour seemed momentarily pointless. In 1969 David Bowie wrote a song that encapsulated the restless search for meaning, and the fear that there is none to be found. But this was a product of its times. As we trudge ever forward, binding and rebinding the frayed threads of our fractured lives, it is a salutary experience to look back upon how far we have come.

And when I see, in the face of my daughter, the fascination for knowledge and discovery that I remember so vividly from my own childhood, I suddenly know the importance of transmission. Of ensuring that she does understand my world, and all the worlds that came before her, and indeed, made her existence possible. All in the hope that one day, when either she, or my Granddaughter or Great Granddaughter, or whoever is the first of my line to step through that space capsule door into nothingness, she will not be searching for meaning, but carrying it in her person, with my love.

[Editor’s note: This article was written before the untimely death of David Bowie]

Douglas Bulloch was born in Canada, grew up in the UK and lives in Shanghai. He spent many years working on the financial reporting side of the oil business before returning to academia to write a political-theory heavy PhD in International Relations. His two young children leave him little time to think, but give him many reasons to

Have you been smoking pot again?