[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]D[/dropcap]eath on an Imagined Afternoon

I’m standing in a dimly lit hallway, big, blue plastic bucket in hand, staring at a heating element which looks as if it’s been ripped from an electric kettle and jammed into a giant metal bowl full of boiling water.

This is how I’m going to die: not with a bang, but with ten thousand volts running through my body as I flop around on the floor, upset about thirty gallons of scalding death, and soil myself all in one swift motion.

That’s the image that’s just flashed through my mind. Now what was it that John, the night manager, had told me? “Oh, you want hot water? Okay, first you must take de bohket, go to the end of de hall. There’s a bowl of water. Off de switch,” he turns to the light switch, “You understand? Off de switch,” turning the light off, “off de switch, take water, fill de bowl again, and on de switch.” He turns the light back on. “Don’t forget to off de switch.”

Off de switch. I’m a little reluctant to do even that. Will I flip the breaker when I electrocute myself? Or is this an old-school system where they’ve just saved money on fuses by jamming pennies into a fuse box instead? The difference is crucial: I’ll either lie dead in my own filth until the cleaning lady comes by in the morning, or I’ll flop around like a fish until the penny jammed in the fuse box shoots out and implants itself in some innocent nun’s head. THESE ARE THE THOUGHTS THAT ARE RUNNING THROUGH MY HEAD.

Maybe I just shouldn’t bathe.

One of the things I like most about Nigeria is that I’ve lost the sense of security that seems to pervade all of life in the United States. It really makes you appreciate life when you’re constantly sure you might die at any given moment. Even Niger felt different. At least there I couldn’t see the billions of parasites that were going to slowly eat me from the inside out.

Even Niger felt different. At least there I couldn’t see the billions of parasites that were going to slowly eat me from the inside out.

Another example: I tried to walk to work exactly one time in the two weeks I’ve lived here. It’s a straight path along a major highway filled with crazy amounts of traffic and smog, and it takes about half an hour. One attempt left me with lungs blacker than a Chinese coal miner’s. Can’t believe I used to enjoy the smell of car exhaust as a kid.

Don’t focus on that last sentence too hard.

So now I take an okada (motorcycle taxi) to and from work every day. I first thought the guys who wear helmets are probably the safest drivers. After several trips, I’m pretty sure they’re just thinking, “Well if we crash, at least I don’t have to worry about my head caving in. Hold on white man!”

Okada drivers fall into three types: the crazy, the suicidal, and the “hey, let’s slalom through oncoming traffic!” Ironically, I’ve found that the bikes that are most beat to hell are usually the safest. They can’t really go much faster than a golf cart, and I’m fine with that as long as we’re not rammed by a petrol truck out on a little romp.

So although the probability of certain death reaches 1 the longer I take the okadas or pull hot water to bathe, I’ll keep doing it. In part because of necessity, but also, I think I’ve learned that the continual fear of death really makes you appreciate all that life has to offer.

Even if that means a high likelihood that someone will eventually peel your face off the tarmac with a spatula.

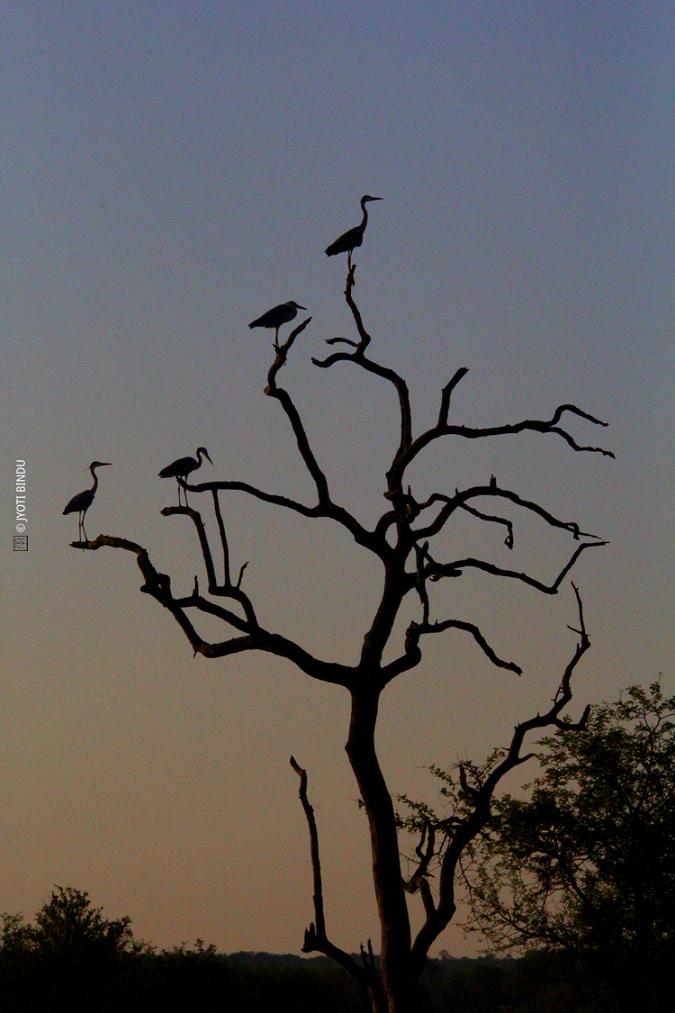

Photo: Jyoti Bindu

Sterling Carter writes on the intersection of political economy, arts and culture, and human rights. He has over five years’ experience on African development, violence and conflict with organizations including Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, and Search for Common Ground. He is originally from Flora, Indiana but pulled up stakes long ago.