[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]here’s a local community theatre troupe here in Harare that’s been around since 1931. They may be amateurs, but they’ve managed to stay in business over eighty years, perhaps by being the only game in town.

I had to stop and think about that for a while. This performing arts group has been through World War II and Rhodesia’s unilateral declaration of independence from the United Kingdom. They’ve survived Ian Smith’s police state and a civil war to achieve majority rule. The theater has seen Robert Mugabe inaugurated as a hero in 1980 and watched him become Africa’s villain par excellence on the international stage over the last decade. Through it all, the troop has maintained its cohesion and is still performing.

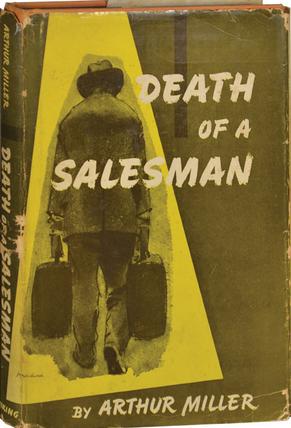

I had the opportunity to catch one of their shows : Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. The play is brilliant in its own right, but I had to ask, how does it translate from New York in the 1950s to Harare in 2013?

The play features Willy Loman, the salesman: an aging dreamer worn out by the rat race in the post-war boom years. He’s a traveling salesman, opened up the whole Northeast to the Wagner Corporation, but as the years have gone by, he’s watched all his old contacts retire and pass on. Old Willy’s still got it though, by necessity. Bills pile up. If it’s not the mortgage that has him underwater, it’s the fan belt on the refrigerator, the broken stove pipe, the insurance premium.

Willy can’t afford to retire, as much as he needs to. His two boys are at home for the first time in a long time, but he fights with his eldest son Biff, while his younger son Happy spends all his time and money chasing women. In the end, Willy realizes that he’s worth more dead than alive. Maybe the payout from his life insurance could get his son Biff back on track, and so the play ends with Willy’s death, ground down by the system like so much grist in the mill.

Re-reading the play, I found myself identifying with the elder son, Biff, lost in the world, unable to find a place for himself, unable to find happiness in other people’s expectations. Struggling and not succeeding. He’s inherited some of his father’s delusions, the three men making stories for themselves that take away the pain of social immobility.

That’s a whole different entry though. What I discovered is that Death of a Salesman still says a lot about America today, but it doesn’t particularly reflect the state of affairs in Zimbabwe.

I’ve been told several times now that Zimbabweans are the freest people in the world. It doesn’t seem right on paper, but it begins to make sense if your conception of freedom falls along the socio-economic rather than the civil-political spectrum.

The economic catastrophe that ended with dollarization in 2009 wiped out bank accounts nationwide. It reset the system to zero for all but the top elites. One guy, let’s call him Tim, told me that he had $20,000 in the bank back when the crisis hit its lowest point. It disappeared overnight when the government scrapped the Zimbabwean dollar.

“Fine, you’ve taken my money, I don’t have to pay off any of my loans,” Tim told me. “It was great! I only wish I had taken out more.”

In his mind, Tim is beholden to no one. He owes no money to anyone. He owns his house outright. He owns his car. He doesn’t have much of a choice on that one. You cannot get a loan for a car in Zimbabwe. It’s impossible. The banks charge interest at eighteen to twenty percent, a by-product of the wholesale collapse of the economy. An entire people saw their life savings disappear overnight, and there has been very little to restore their trust in the banking system. Without liquidity, the banks have nothing to loan and must charge interest equivalent to the average American credit card.

No one in Zimbabwe has the sort of career mentality that permeates the American system. Instead, nearly everyone I speak to has several different projects ongoing at any one time. They have had to diversify, to hedge their bets against the threat of a return to the volatility of 2007 and 2008. One woman has an IT service, a gardening service, and runs a cocktail catering business. At any one time, any one of her enterprises could be losing money, but as long as one is in the black, she can keep her head above water.

Of course, this is common in Africa, where you’ll often meet people who work security at night, maintenance during the day, but have at various points taught primary school, worked as a mechanic, or sold SIM cards on street corners. You don’t, however, expect to find the same thing with middle-class entrepreneurs.

At a critical moment in Death of a Salesman, Willy complains to his neighbor Charley that his boss, Howard Wagner (the snotnose who took over after his father died) laid him off. Willy remembers when Howard was in swaddling clothes. He remembers Howard in diapers, worked with his father, even suggested the name Howard. “Imagine that?” Willy says, “I named him. I named him Howard.”

Charley replies: “Willy when’re you going to realize that them things don’t mean anything? You named him Howard, but you can’t sell that. The only thing you got in this world is what you can sell. And the funny thing is that you’re a salesman, and you don’t know that.”

[quote]In Zimbabwe, which has experienced

so much pain and upheaval in the

last decade… relationships are still alive,

still important. They’re the only

thing that carried so many through

such trying times[/quote]

Zimbabweans could take Charley’s side in this case. The only thing you got that matters is what you can offer other people. But they also have learned hard lessons in community. One businessman told me that the only thing that got him through the crisis was his connections. Once you made a sale, you had to get the Zim dollars out of your hands as quickly as possible. It was like a game of hot potato, but one that would undoubtedly end in ruin.

With prices doubling every day, you didn’t want to get stuck with trillion dollar notes worth less than the paper they were printed on. Without food on the shelves, and with people literally starving, a community of black market guys bought food from farmers, and established an entire network of distribution to the poor and needy, some charitable, some for the right price. It was the only way to survive. If you didn’t have friends, if you didn’t have connections, you starved.

That’s why Tim claims that Zimbabweans are categorically freer than anyone else in the world. They had to build communities. They had to find help. They had to do it outside of the government. As a result, he owes money to no one. He is beholden to no one in power; no one has the ability to deny him food, clothing, or shelter. He has his friends, he has his community, and if anyone ever wants to come and mess with him, he can stand up and resist any intimidation.

Granted, he’s in a much better place than the majority of Zimbabweans. Miller’s play wasn’t written about the upper crust of American society, but rather the lower-middle class who struggled to make their way in America’s ‘make-it or break-it’ culture. Willy just barely survives with Charley’s help. His neighbor offers him a job and gives him fifty dollars every week to help scrape by.

There may also be a bit of bravado in Tim’s claim that he can stand up in resistance to intimidation. An old Indian woman in Bulawayo, a friend’s mother, told me about her former life in Mozambique. When the rebels came for her and her husband, they owned a little shop, selling basic goods to the community. They didn’t owe anyone anything. They had friends, but after several months of violence and intimidation, they had to leave Mozambique with little more than the suitcases they could carry. They came to Zimbabwe with nothing and had to build it all back again. Even the best of friends sometimes can’t you from organized violence, whether its rebels or the state.

Miller, in the end, is cynical. An avowed socialist, he empathized with America’s working man, pressed to the limit by corporate greed and the capitalist system. Willy is a dreamer, the last of a dying breed, when deals were made on personality and sealed with the shake of a hand. He thrived in that system, but he hasn’t been able to adapt. To Miller, Willy’s relationships are dead and meaningless.

In Zimbabwe, which has experienced so much pain and upheaval in the last decade, these relationships are still alive, still important. They’re the only thing that carried so many through such trying times. Like America, however, what matters is what you can eat. People still have to scrape and fight to survive.

In Zimbabwe, like in many places, you can’t dine on friendship, but you can dine with your friends.

Market image by the author.

1950s street image: Public Domain.

Sterling Carter writes on the intersection of political economy, arts and culture, and human rights. He has over five years’ experience on African development, violence and conflict with organizations including Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, and Search for Common Ground. He is originally from Flora, Indiana but pulled up stakes long ago.