[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap] am excited; the Victoria and Albert Museum have launched a hefty walk-through exhibition dedicated entirely to video games, and it does not disappoint. Discarding the usual narrative of making a case for video games as art, Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt seeks not to convince but to uncover, explore and relish, making for a forensic celebration of games and their impact.

A scene from Journey, one of the games the exhibition explores in depth

Almost from the get-go the exhibition blends in user-generated content, recognising one of the most wonderful and oft-overlooked aspects of the world of video games: how interactive and creatively inspirational it can be for players. Accompanying a visual playthrough of horror RPG Bloodborne’s Cleric Beast battle is the rambling commentary of a selected YouTuber, a clever way to illustrate another dimension of the game. I prefer lore-heavy background narration to words of encouragement, but the addition to a screech-laced boss battle of a calm coaching voice explaining the merits of persevering and keeping your cool reveals the shiny motivational lining to this otherwise grim Lovecraftian horror game. This approach pervades the exhibition; we’re not just told what games we should be paying attention to, but what we can hope to gain from the experience.

A guided-meditation-style narration accompanies a Bloodborne playthrough

There’s a diverse blend of games on show and it’s far from a static display of polished final products, exploring both the inspiration and impact of the pieces through physical evidence of early creation-stages and fan responses. Perhaps this is why the exhibition feels so juicy and thorough, fleshing out the medium of video games as so much more than impressive design. Polished gameplay footage sits alongside rudimentary sketches, a creator doodle of a Splatoon squid dressed as Super Mario bringing as much joy as the ethereal concept art for The Doll from Bloodborne.

A detailed section on the production of the multiple award-winning Last of Us is followed by a line of chunky, pastel-coloured smartphones dangling from the ceiling upon which you can play Consume Me, a Tetris-like food-stacking game commenting on diet culture. It’s an inviting interactive setup, a space discarding games industry snobbishness for temptation and glee and a call to join in.

A spectrum of No-Man’s Sky playthroughs

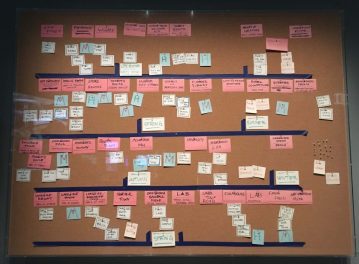

As a lover of visualised planning, lists and organisation in general, a highlight was seeing the original narrative charts for Journey and The Last of Us—an Excel spreadsheet for the former, a massive corkboard for the latter—because it’s so revealing seeing the early, informal, still meticulous development stages of something that’s had you awestruck in its final form. It was surreal too, seeing a spreadsheet cell containing the simplistic phrase ‘you love cloth, but the machine kills them’ and recognising it as the basis of a plot point in Journey that genuinely had me welling up the first time I played it. To see the minutiae that goes into making a game, into developing a textured player experience, transports you miles from the outdated notion that video games are a frivolous waste of time.

The Last of Us in its early, corkboard-based incarnation

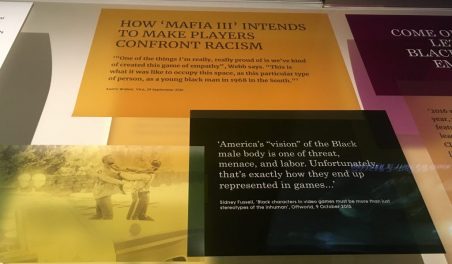

The Disruptors room is the urgent heart of the walkthrough, a crucial segment dedicated to representation and sociopolitical context, studded with glowing banners querying the inclusion (or lack thereof) of queer, female and non-white narratives in mainstream video games. The objectification of women in games is examined alongside an overview of Anita Sarkeesian’s Tropes vs. Women series, Mafia III is praised as a rare example of centring black protagonists and their narrative in a high-profile game, whilst How Do You Do It demonstrates how a game can explore something as sensitive as a child’s understanding of sex. This room brazenly highlights the hard work of those fighting to bring diverse, accurate and fair narratives to the forefront of gaming—I wonder whether the folding in of current and future sociopolitical context will become more common in a museum format usually so focused on the relevance of the past. It didn’t feel out of place here, and despite having overheard a fellow visitor helpfully ‘explain’ the entire room to his female companion, I left the room feeling excited and optimistic about the same medium that has so many times before excluded myself and others.

Journalistic extracts stress the importance of black representation in Mafia III

More playful aspects lie ahead. A huge screen showcases esports tournaments and fan-generated content, covering everything from an accurate Minecraft replica of the Death Star to cheery cosplayers dressed as D.Va from Overwatch. A mini-arcade was a neat round-off to the experience: a reminder of what gaming has to offer in terms of communal, colourful, bright light-studded play.

In short, I loved it: I loved that we saw process as well as product, that there were things to pick up and interact with, and the impressive effort taken to explore the sociopolitical impact of video games. I loved that my female friend and I didn’t feel out of place wandering through. This is an exhibition that does not patronise or exclude; it revels in what video games have achieved so far without selective blindness to the industry’s problems with diversity. It applauds award-winning favourites whilst amplifying small-name game changers, keeping a close eye on how they’re shaping the industry’s future, and I highly recommend a visit.

Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt is on at the V&A. For further information, visit the exhibition page.

Rhiannon is a a poet, writer and member of the Feminist Internet collective. A lover of music and the outdoors, she writes extensively on the subject of islands – particularly Cyprus, where she lived for eight years. She has a bachelor’s degree in English Literature from the University of Exeter, and has had poetry shortlisted for the Bridport Prize and the National Poetry Prize. Currently studying MA Narrative Environments at Central Saint Martins, she is interested in gender, islands, liminal spaces, and the effects of environment on the psyche.