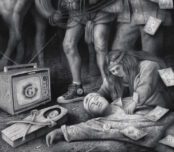

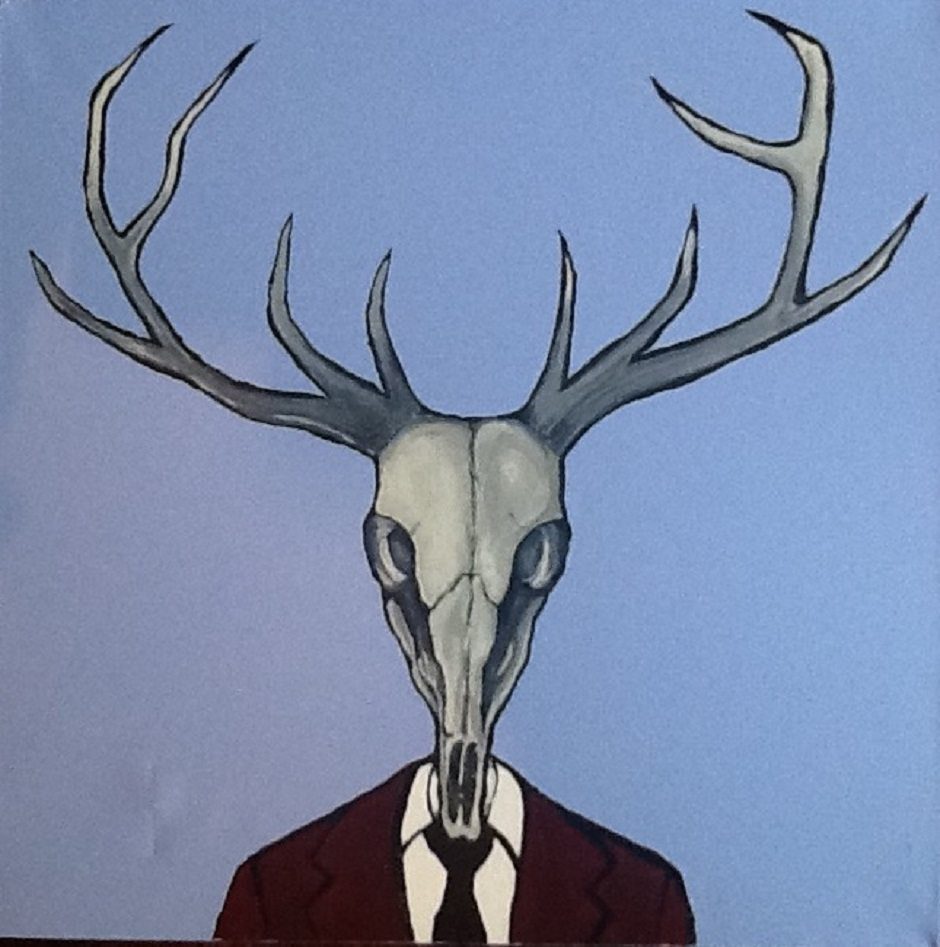

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]W[/dropcap]hen the chips are down and you are face to face – does The Devil really have The Best Tunes?

During what were euphemistically called ‘The Troubles’ (in my view, one of history’s most ironic euphemisms), I spent some time in Belfast talking to musicians, artists, poets, film-makers, and writers and photographing the political wall murals that had proliferated on every available upright flat surface. It wasn’t too difficult to get arrested for asking too many questions at that time but the raison d’etre for these visits had been supplied by a television company so I wasn’t overly concerned.

They had been thinking about a piece questioning the notion that in times of trouble ‘the devil had the best tunes’ – and not just the music – even though we all know that The Blues is leading contender for the Crossroads Devil’s Music Award. In such a deep, complicated and long lasting conflict, how did this theory stand up in the eyes of the broader ‘creative’ community that was dealing with some terrible events on a daily basis? The outcome may surprise you or not, but I’ll get to that….

Given that the discussion about the importance of having a young upcoming driving force involved in the blues world both as players and song-writers is, quite rightly, never going to go away, maybe it is the young you think you should first look to for support for any change or transformation.

Certainly, so far as the public art was concerned, it seemed inevitable that art students and the art schools would be in the forefront of any ‘revolutionary’ gestures. Echoes here of the graphics omni-present in the Hong Kong street action – and to a lesser degree in Scotland recently. Yes. They certainly had the best ‘tunes’ on the walls.

Also, you only have to look at much of the breakthrough music that also emerged from the art schools in England during the 60’s and 70’s and again in the punk period to make the connection. Much of the outstanding mural work supporting the IRA in Belfast came from this art source, not unusually regarded as a place where support for a cause was de rigeur.

The difference between the murals in The Falls and The Shankill is unsurprisingly stark – one pushing boundaries and creating edgy often threatening landscapes questioning the status quo and the other using traditional images appealing to a very different audience. You could see why one was regarded as ‘exciting’ and the other somewhat ‘safe and dull’. King Billy on his white horse and Union painted kerb-stones versus the three dimensional balaclava action and glinting rifles paintwork.

And yet, a remarkably different picture emerges once you talk to the poets, playwrights and the musicians. I lost count of the number of times I heard the comment that ‘I am a poet/song-writer. I do not write to order. If I choose to write about the troubles it will be on my own terms and in my own time’. Similarly, with playwrights and musicians, who almost without exception echoed this view – and Dylan’s refusal to be type cast as a protest balladeer came to mind.

Yes, of course, quite brilliant songs were written on the subject and Irish folk and blues has often been the home of some quite fearsome chronicling of battle. Also, playwrights Synge and O’Casey both have previous form entwining the political background into their work.

But here both contemporary poet and songster saw no need to either take a side or produce a work simply to state or justify their position. There was a clear refusal amongst the majority to sign up to one side or another. Unlike the art students, they saw no need to join a movement or for a public utterance to support their artistic credibility – despite some getting mightily and publicly criticised in the process. However, when they did emerge on the subject, the likes of Michael Longley, Seamus Heaney, Paul Durcan (outspoken critic of the IRA) and Ronan Bennett (a fluent supporter) would blow you away with the power of their work, whatever tune they were singing. They were speaking both for themselves – and often on behalf of the disenfranchised of all sides.

The photographers and film-makers were, as you would expect, also in no mood to compromise with any side in the conflict. They, like the wordsmiths and musicians, were not to be put in a box and indeed David Hammond, singer, director and writer, who ran the ground-breaking and influential Flying Fox Films, was regarded as a ‘creative subversive’ as his house was always full of writers and musicians from every corner of every divide.

Similarly Belfast Exposed, home of contemporary Irish photographers simply saw themselves as essential seeing-eye commentators. Their job was not form-filling for an agenda. They took pictures on their own terms. No drum beating here, either for or against any Devil. Pictures of pain and humanity from either side of the wall.  Walk into any music bar or club and the story was the same. Powerful songs coming from either side but the really powerful stuff was about what it was doing to the people, their hearts and their future – whatever their view and wherever they sat. A genuine quest for good – and for peace.

Walk into any music bar or club and the story was the same. Powerful songs coming from either side but the really powerful stuff was about what it was doing to the people, their hearts and their future – whatever their view and wherever they sat. A genuine quest for good – and for peace.

This is a grand tradition of the blues world, from the heart-breaking anthems about race, the unions, bigotry, and discrimination through to those beautifully crafted three hankie works on the unfairness and the joy of love. Nobody tells them what to say. Like JJ Cale, they look over your shoulder and say it for you wherever you are coming from. They are also our commentators on humanity and some of its shit consequences.

This conversation is not about the rights and wrongs of the Belfast situation and the dreadful things that happened. It is about what happens to our creative artists in that situation and whether they are obliged to take a position. Certainly they were not working under a threatening mad dictatorship so their freedom was not compromised, but nevertheless there were undoubted pressures on them to pin their colours to the flag. This didn’t happen as a matter of course and when it did, it happened to their rules and in their chosen moment. A refusal to be co-opted to any devil’s cause was normal and long may it continue.

I found that hugely encouraging. I look particularly at those song-writers now working in the UK and find poetry about passion at every level, from personal trauma, hit and run thrill and love, to the way the world is moving: its cruelty, its pains and pleasures. There may not be streams of invective about the state of the nation but the commentary, when it comes, is as powerful and potent as ever and it is theirs.

As they say, the Devil better take a rain check.

Illustration by Dan Booth not to be reproduced without his express prior permission.