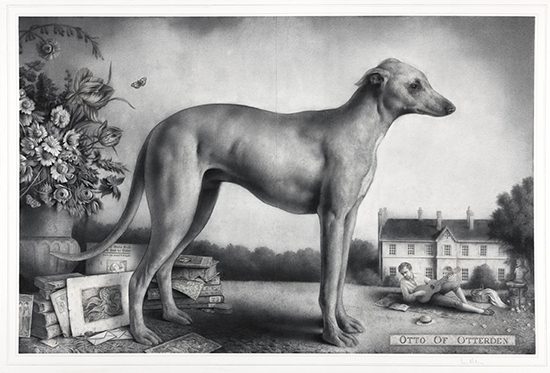

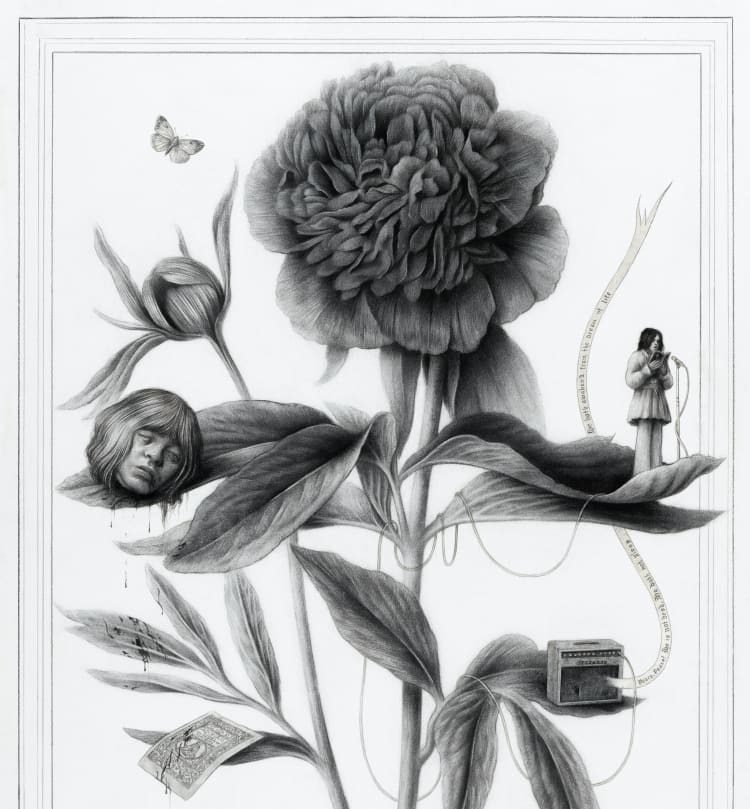

Sverre Malling weaves together references from art history and contemporary culture to create mysterious and highly-detailed compositions that occupy a kind of liminal space between beauty and the grotesque.

His latest exhibition Adieu to Old England at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, Wandsworth, presents a new collection of drawings that explore and celebrate marginalised characters and narratives from recent and distant English history.

Below, Malling discusses his artistic and literary interests, and how his work fits into the wider Norwegian art landscape.

How do you begin working on a new series? Do you have an archive of materials that you continually refer back to, or do you seek out new materials relating to a specific idea or theme?

As my current exhibition is in London, I chose to dig deeper into my interest in English culture. Ever since I was a university student, I’ve had a weak spot for English art history, dating from the Romantic period right up to today. It is interesting, far-reaching, and multi-faceted.

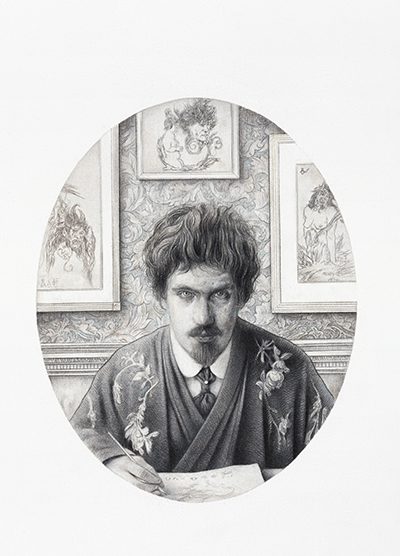

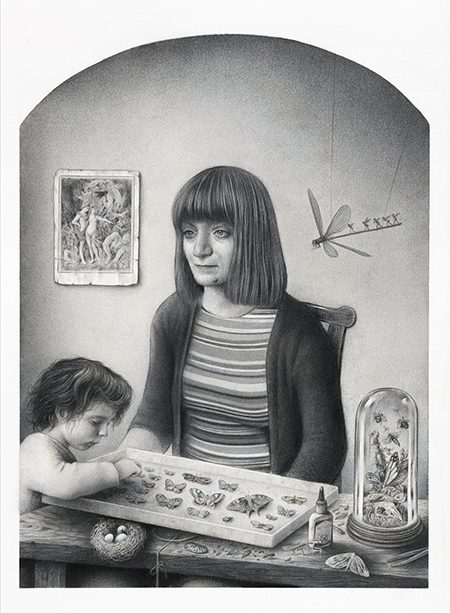

Adieu to Old England is a celebration of the diversity of England’s well kept cultural treasures, the lost visionary heroes, esoteric outsider artists and anachronistic romantics. In the works, I highlight curious talents like Algernon Swinburne, Austin Osman Spare and Stephen Tennant, but also creators from our own time such as Tessa Farmer, Genesis P-Orridge and Shirley Collins.

For me, engagement with art history is an unending and exciting voyage of discovery. I am drawn to digging up the eccentric artistries – moving beyond the traditional, mainstream stories, the so-called hegemony. If you plunge past the accepted ways of conceptualising things, you have the opportunity to uncover a rich plethora of overlooked women and men in dark and dusty corners. One aim of this exhibition, on a purely symbolical level, is to lift up a few of these visionary heroes – the artists who have not been recognised by the conventional canon.

Do you think your position as Norwegian artist allows you a different perspective on English heritage and culture that can perhaps evade the traps of conventional narratives?

Yes, the fact that I’m entering into a sort of dialogue as a Norwegian can perhaps help create an unexpected perspective on a common narrative in England. The process of creating the drawings for this exhibition has been almost that of an archaeological dig – where one in a way attempts to unearth characters and rarities in England’s cultural history. Many of the historical figures I draw upon had utopian ideas of how the world should be, but their dreams remained undeveloped either because they were marginalised, or lacked a privileged position within society. I happen to be of the opinion that the battle is not lost for such rejected perspectives, since their rehabilitation doesn’t just revive the forgotten or marginalised, but can further develop an unrecognised potential which was always there from the beginning.

What appealed to you about drawing, and how has your approach to the medium changed over the years?

I am very fond of the personal aspects of artistic production. My work is a personal investment in analogue technique, in a craft. But I also enjoy combining this age-old method with impacts of the contemporary access to visual culture, the digital flow of images online.

My technique may function as an immersive medium of translation and framing for these fragmented reflections. The slow immersion in the medium can mature the fragments into a coherent experience. I want to remove myself from the mechanics of production and attempt to reach, or embrace aesthetics of intense attention, in which I am deeply immersed in the material and the act of drawing. I really enjoy immersing myself in details. I also believe that analogue media allow us to appreciate the necessity of immersion and meditation and concentration. It represents a focal point, an anchor of sorts, in a world in constant flux.

Any key influences on your practice (artists, movements, books)?

Well, my drawings generally have a literary slant. Traditional technique, but often with motives centring around our own time. I try, basically, to fill established genres with new content and allow them to circulate in new and actualised contexts.

In the field of tension between the old and the new, there is room for reflections on traditions and schisms. The road runs all the way from Georgian style through the Victorian anachronisms; the Arts and Crafts movement and the eccentric figures of the 1920s and 30s. I have also attempted to show parallels in our own time. For example, I have drawn a giant portrait of the artist Tessa Farmer, whom I admire greatly.

How do you think your drawing practice fit into the contemporary art scene in Norway and the wider Nordic artistic landscape?

That’s not so easy for me to say. I think that I identify with a larger tradition that still thrives in Norwegian art. It has to do with feelings of roots and origins. Aspects of the Norwegian landscape tradition are certainly present in my former drawings. Norwegian folklore has a dark and more primitive side, which has also influenced older artists. Artists as Theodor Kittelsen, August Cappelen and Lars Hertevig express something supernatural and eerie which I like.

This art has also — perhaps paradoxically — been a part of the national consciousness. Landscapes helped to form and flesh out the nation, helped us create archetypes and construct a visual identity. I have always been very eager to examine what exists on the fringes of a hegemony, or outside a cultural hub.

Norway is young nation in the cultural sense, and our artistic heritage is in large part a reaction to alienation, precarity and exclusion. You see Norway has a colonial history, having been culturally dominated by Sweden and Denmark. There is a strong yearning after myths, sagas and pagan beliefs which bloomed in the periphery of great nations in Europe. Many of my works are founded on Nordic mythology and sagas.

Can you talk a bit about the function and influence of fairy tale narratives and symbolism in your work, and how this might complicate or reorganise our perception of “reality”?

It is no secret that my drawings reference illustration art from the 1800s. I am still bewitched by artists like Arthur Rachkam, Richard Dadd, Walter Crane and Aubrey Beardsley. This stems from childhood, and for me, it continues to offer an expansive world of imagination. Much of this visual world shares points of contact with the boundless fantasy of childhood, which we, in the process of becoming grownups, must let go of – the stories of trolls, elves and gnomes!

I feel that I am constantly shifting between these positions, between tradition and playfulness; between the cultivated and the vulgar, the withdrawn and the outré, the adult and the childish. Hopefully, this series of dualities makes the drawings more mysterious and full of contradictions. The fanciful is also lurking there. I like to offer surprises, if I can.

There seems to be an underlying gothic atmosphere in terms of both your aesthetic style and the subject-matter. What drew to you this particular genre, and how does it reflect the themes you’re exploring?

If there is such a gothic atmosphere, I think it can be related the dark spirited imagery of the 19th century, and British horror films (Hammer Productions, for instance). The latter are toned by swinging London, or British 1960s pop culture, mixing both good and bad taste. The 1960s also marked a re-evaluation of symbolist art and its slowly increasing appreciation.

At the same time, there was a renaissance of Neo-religiosity when the hippy movement, and other new groups that held spirituality in high-esteem, began to show interest in the same questions as those who had developed esoteric ideas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. So, to me, it feels natural to portrait Brian Jones in the same manner as Algernon Swinburne.

There is also line of connection all the way back to the Romantic period and a morbid romantic sentiment that dates back to the work of poets such as Shelley and Keats. They opposed the establishment, and the Pollyanna, overblown emotional life of youth. In their worlds, tragic occurrences took on a heroic patina. We find the same romanticised fantasy today in Princess Diana’s beautiful but tragic life, which is the inspiration behind my drawing England’s Rose / Hourglass for Diana.

What’s the function of white space in your artworks (in the series of drawings entitled ‘England’s Hidden Reverse’, for example)?

It’s probably got to do with me aiming for a greater width in my works and formal expression. This leap also applies to size of format: from the microscopic and detail oriented, to the large compositions.

And finally, due to current restrictions, your current exhibition is only available to view online – how do you think this digital format impacts on the viewing experience of your works and art, more generally?

I think it’s too bad because the drawings should be seen “in the flesh”. It has something to do with the characteristics that emerge on paper and in the surface treatments; it has to do with a sensitivity for materials and the physical format. Unfortunately, I don’t believe that the digital reproduction does justice to the drawings and the qualities that inhabit them, but I am still happy about the exhibition and all the attention that comes with it, despite the lockdown. When things change out there in the world, one has to be flexible and ready to adapt.

There is also an elegant book that can be ordered through the gallery. The book is rich in illustrations and contains many closeups of details. Also included is an interesting essay by religious scholar Per Faxneld (author of Satanic Feminism and The Occult Fin de Siecle). I hope as many people as possible are able to read the book!

‘Adieu to Old England’ runs until 27 February 2021 at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, Wandsworth and online via kristinhjellegjerde.com/viewing-room/29/

Featured Image: Otto of Otterden, 2020, Sverre Malling. Photo by Thomas Wideberg. Copyright Sverre Malling / Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.