[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]t’s not often we feel compelled to feel pity for psychiatrists.

Usually pigeonholed as bookish types who spend therapy sessions nodding vaguely whilst they surreptitiously fill out their tax returns, or send Wassup messages, or work on their backswing whilst the hapless patient pays them handsomely for couch time.

At least that’s what comedy stereotypes would have us believe. But pity them we should, for new credence has just been given to Jungian psychological theory, which means they’ll have to listen to patients describing their dreams. And as anyone who’s ever been on FaceBook before noon will attest, other people’s dreams are the very epitome of turgid.

Dream images could provide insights into people’s mental health problems and may help with their treatment, according to a psychology researcher from the University of Adelaide.

Dr Lance Storm, a Visiting Research Fellow with the University of Adelaide’s School of Psychology, has been studying dream symbols (or “archetypes”) and their meanings, as described by the famous psychologist and psychiatrist, Carl Jung.

In the early 1900s, Jung proposed that these archetypes were ancient images stemming from humans’ collective unconscious. He believed that dream symbols carried meaning about a patient’s emotional state which could improve understanding of the patient and also aid in their treatment.

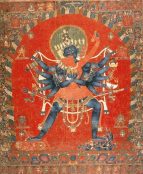

“Jung was extremely interested in recurring imagery across a wide range of human civilizations, in art, religion, myth and dreams,” says Dr Storm. “He described the most common archetypal images as the Hero, in pursuit of goals; the Shadow, often classed as negative aspects of personality; the Anima, representing an element of femininity in the male; the Animus, representing masculinity in the female; the Wise Old Man; and the Great Mother.

“There are many hundreds of other images and symbols that arise in dreams, many of which have meanings associated with them – such as the image of a beating heart (meaning ‘charity’), or the ouroboros, which is a snake eating its own tail (‘eternity’). There are symbols associated with fear, or virility, a sense of power, the need for salvation, and so on. “In Jungian theory, these symbols are manifestations of the unconscious mind; they are a glimpse into the brain’s ‘unconscious code’, which we believe can be decrypted,” he says.

Dr Storm argues that Jung’s theories have practical significance and could broaden the range of options available to patients undergoing treatment for mental health problems. “Our research suggests that instead of randomly interpreting dream symbols with educated guesswork, archetypal symbols and their related meanings can be objectively validated. This could prove useful in clinical practice,” he says.

“We believe, for example, that dream analysis could help in the treatment of depression. This is a rapidly growing area of mental health concern, because depressive people are known to experience prolonged periods of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is directly linked with emotional processing and dreaming.”

Source: University of Adelaide

Image: Credit: Dr Lance Storm, University of Adelaide, from multiple sources including Wikimedia Commons.

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle