[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]t was an October morning and, the air rang with (what should have been) the siren’s song of everything that ‘Frieze week’ embodies in the arrows stretching across the art world’s calendar.

However, as I stepped off the train at Euston, eyes tattooed with a densely scribbled map of tips offs, recommendations and Internet research, I was greeted by the lick of the type of rain that is undecided as to its temperament.

It was a grey day, teetering on the edge of tumultuous darkness and the kind of blinding Autumn light that has the nostalgia of summer in its nonetheless undeniably wintered caress. Underfoot, rotting leaves exhaled cloying pungency, a metaphor for the beauty in decay.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) The Prodigal Son,c. 1495–96 Pen and ink, 215 x 220 mm © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, Inv. SL, 5218.173

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) The Prodigal Son,c. 1495–96 Pen and ink, 215 x 220 mm © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, Inv. SL, 5218.173

It tugged at memories of walks through the woods surrounding my home in Warwickshire, rooting around for the little fragments of shells and pods that form themselves into totems to corporeal traces of where I have passed days before. It was recollections of these walks – which, although affecting aimlessness, were fuelled by a hoarder’s drive for a palpable connection with the world and the body’s place within it – that informed my subsequent steps.

Freud’s study also apparently swarmed with archaeological finds; talismans of the unconscious through which he observed his subjects. The figurines and statuettes, displaced from their origins in Rome, became recollections of points of identification with some instinctive urge experienced whilst travelling. As we plunge new depths and journey out, we somehow stumble upon the familiar: a sense of ourselves, a sense of home.

It was a moment before I realised that I was being carried on a cognitively familiar cultural trail though, with no fixed notion of what I might find. I switched off my mobile phone, disconnected my emails and followed the scent of the dying leaves – away from the main road.

The Young Dürer: Drawing the Figure

Some initial mistrust of the peripatetic brought me first to the steps of The Courtauld. As I riffled through my bag for a pencil and notebook– in order to look purposeful from the outset– I pulled out a press release for the Antiquity Unleashed show that had been lurking (admittedly only a few levels) beneath my ‘Frieze maps’. I strode through the Young Dürer: Drawing the Figure exhibit, intent on utter absorption to the task at hand.

An initial confrontation with the scrawls and theorizations on the part of the influential art historian Aby Warburg (1866-1929), seemed at odds with his investigation into the passion – rather than popular idealism of grandeur and nobility – instilled in classical drawing and sculpture. Admittedly the premise of his 1905 lecture at the Hamburg Concert Hall: ‘Dürer and Italian Antiquity’– (illustrated with original works by both Andrea Mantegna and Dürer) which forms the flesh of this exhibition– was admirable.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) Self-portrait (verso),c. 1491-92 Pen and ink, 204 x 208 mm Graphische Sammlung der Universität, Erlangen, Inv. B155

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) Self-portrait (verso),c. 1491-92 Pen and ink, 204 x 208 mm Graphische Sammlung der Universität, Erlangen, Inv. B155

However, casting around at the seemingly austere array of classically inspired drawings and formidable case notes, I felt somehow that, having been led by the promise of a depiction of humanity, I had rather been ensnared in a Renaissance web of concept over content.

Peering closer, I was caught off guard by an evocative gesture that appeared to stem from beyond the small frames. Something told me that my eyes, despite my resolution, must have wandered on the walk through. The intensity of the emotion and invitation for empathy with the human condition, which the small studies so powerfully elicited, suddenly seemed to originate not from the classical construction, but rather in the expressive naivete of the anatomical drawings from life at the opening of the adjacent display.

The beautifully composed ‘Melancholia’ is accompanied by an explanation of how melancholy is one of the four classical temperaments of human character, and therefore a vehicle within art for the realisation of true emotion. Warburg’s devoted studies prove consistent again, and yet, the looks of anguish and pain now appear rendered in spite of reverence to antiquity.

[quote]Life studies and Classical

studies appear to conflate

– the drawings no longer

illustrative but suggestive[/quote]

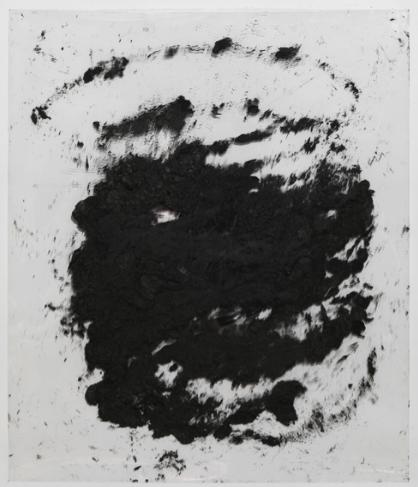

A blackness creeps to the edges of my subconscious, the lightness of conceptualising despair becomes clouded with swirls of dark. Textured blobs and lumps of black material threaten to creep across the walls of the small anteroom and a menacing notion of ‘a presence’ overwhelms the peripherary of my vision.

Richard Serra

I realise that the sculptural drawings of Richard Serra, displayed at the gallery’s entrance, have accumulated at the edges of my self-declared tunnel vision and have been impelled, by association, into my consciousness. The ostensibly fragile works on clear plastic sheets hover with a quiet awe, challenging the hallucinatory clouds of shimmering colour of the Impressionists, personifying the capability to feel that is realised in despair.

Richard Serra Courtauld Transparency #4, 2013 Litho crayon on Mylar, 76.2 x 61 cm © Richard Serra

Richard Serra Courtauld Transparency #4, 2013 Litho crayon on Mylar, 76.2 x 61 cm © Richard Serra

I glance at the press release for The Young Dürer and am immediately drawn to the quotation:

‘For in truth, art lies hidden within nature; he who can wrest it from her has it’

I look back at Warburg’s assemblage with a sense of catharsis. The lines of his hand-drawn intricate flow diagrams, mapping the links from the Renaissance to Ancient Rome and back, seem at once less occlusive – reforming themselves into the links between one artist’s hand and another’s. Ovid’s pen becomes Mantagena’s becomes Dürer’s – a stream of life, rather than dusty intellectual seclusion. Life studies and Classical studies appear to conflate – the drawings no longer illustrative but suggestive.

Courtauld Transparency #6, 2013. Litho crayon on Mylar, 76.2 x 61 cm © Richard Serra

Courtauld Transparency #6, 2013. Litho crayon on Mylar, 76.2 x 61 cm © Richard Serra

Serra and Dürer: works alive and yet frozen in time. The layers of Serra’ black litho crayon reach out from what seem to be the chasms of the earth – just as Dürer’s figures are resuscitated from their orthodox origins. There is a unifying tremor of death; personal and communal, historic and present. When one excavates the past a new identity is involuntarily inscribed onto existing objects, the dead live in us.

As I found myself caught once again in the eddying tides of The Strand, I realised that I had been discussing Serra’s work the day before with a young sculptor who had been enlivened by the delivery of a sheet of steel for a commission.

Daniel Silver

A phone call carries me back in the direction of Tottenham Court Road which, for a moment, thwarts my intentions to drift. I had originally met my companion with his uncle one rainy, wine-filled evening when the conversation had inevitably dried up between myself and my then partner. I had been happily enraptured by an overheard mention of ‘pirates’ and, from there, the night invited its contentment. My relationship fell into the abyss, my friendship with H continued, and thus we found ourselves searching for the entrance to the new ArtAngel installation: Dig.

Daniel Silver: Dig. Photograph by Marcus Leith. Image treatment by Modern Activity

Daniel Silver: Dig. Photograph by Marcus Leith. Image treatment by Modern Activity

Already the spirit of adventure was upon us as we questioned whether the unobtrusive entrance, littered with plastic bottles, warning signs and metal grilles was in fact the correct place. Luckily H had a moment of revelation and exclaimed that he had driven past with his uncle a few days previously, and had just recalled how he had intended to visit. With this confirmation, I began quietly congratulating myself for the choice of meeting place, as I remembered that H had studied archaeology and classics.

[quote]The figurines are at once

haunting and homely, their

cracks and contours perhaps

reminding us of something –

it might even be ourselves[/quote]

As we enter what appears to be the site of community project – complete with welcome desk and enthusiastic team of volunteers in wellington boots (clutching steaming mugs of tea and digestive biscuits) – we are greeted a field of fragmented mutant bodies – the residue of a bygone classical era, exorcised from their earthy graves and displayed on wooden tables.

That is until, on closer inspection, we see the marks of the artist Daniel Silver who (having taken inspiration from his childhood in Jerusalem, the archaeological nature of this derelict cinema and the artefacts of Freud’s study) has cast each relic himself, adding his own embellishments and finger prints. The figurines are at once haunting and homely, their cracks and contours perhaps reminding us of something – it might even be ourselves.

Below, strangely distorted male heads and a marooned bust of Freud – bulging with what looks like a gestation of the smaller heads upstairs – apparate from the gloomy depths of the tomb-like, flooded basement. As we seize upon the stories of Aeneas, Achilles, John the Baptist and Jesus to ground with explanatory narratives the two ghostly figures on the brink of the murky waters our recollection splinters, multiplies and tumbles over. We are no longer defined by our reasoning, as meaning slips.

The sound of falling water accentuates the feeling of displacement from the street above, where our rational selves walked sometime before, creating a cacophony of silence that is as threatening as it is empty. The day’s sights and sounds all seem to focus into this one moment of nothingness, the fragments cohere and, as we ascend, I observe that the tiny figures seem to be dancing, conversing, and conspiring amongst each other.

A leg flows into an arm, into a leg. Wasn’t laughter a sign of hysteria? We quickly muffle ours beneath the uncanny ambience.

From below though, Freud himself is crying out for analysis and a haunting rhythm permeates the inanimates – Life haunts this deathly display.

Leaving the site, we can barely see where we have been – time, memory and the unconscious remain indistinct – a fragmentary riddle to be solved. I puzzle this as the clouded sky on the train is suddenly split with a blaze of sunlight over the rooftops of my hometown, which, in their newly gilded baptism, have never looked so sacred.

It is enough to temporarily distract me from reading Virginia Woolf’s Street Haunting. For a moment the figures of writer, artist and archaeologist distil into one being – searching beneath the surface of the buzz of life for a sense of who they are, where they have come from and where they are heading.

My Blackberry flickers back into life and only then do I realise that I haven’t been to Frieze. For some reason, I had thought that – like everyone else – I had.

Dig : 12 September – 3 November 2013 at The Odeon Site

Antiquity Unleashed: October 2013 to 12 January 2014 at The Courtauld Gallery