Over the last decade, Ed Atkins has explored the relationship between the corporeal and the digital, the ordinary and the uncanny, through high-definition animations and elliptical writings.

The artist’s latest show at New Museum features a new body of work made with technologies that profess to “capture” life, including a video that documents a telephone conversation between Atkins and his mother, reflecting on notions of intimacy and distance.

Here, Millie Walton speaks to the artist about his practice of writing, performance and allowing for as much improvisation as possible.

You’ve described your work at the New Museum as an “essay about distance.” What do you mean by that?

I suppose I meant a whole raft of “distances”, and that the show speaks to and models them. The distance between me and my mother, between her and her mother; hereditary distance; distance as loss; literal distance seemingly collapsed by technologies of telecommunication; a kind of insurmountable irrecuperability or unsurmountable distance that lies between the relationships of the show – familial, epistemological, mortal, etc. “Essay about distance” is a little pat, but it’s a convenience to fold it all and ask that noun – and that mode – to hold it.

How did the title Get Life/Love’s Work come about?

I tend to vacillate between pretty straightforward, literal titling – and more lyrical, obscure things. This title is pretty much the former. ‘Get Life’ relates the act of capturing performed by the technologies I use to make the videos, and also a vernacular term of permanent imprisonment. It’s also an imperative that rings hollow like a wall vinyl motto, maybe. ‘Love’s Work’ comes from Gillian Rose’s memoir of the same name. The work in question is performed in the show, I think. Or attempted to. That is, the transformation of all kinds of pain into love. It’s pretty direct, really.

You appear in one of the pieces as a kind of digital alter ego that’s perhaps more recognisably “you” than the other avatars that you voice/perform. What’s it like seeing yourself represented in this way?

I’d actually say this one looked just as little like me as all the others that’ve gone before. This one is far more *like* me because I am *being* me while occupying it. As in, despite appearances, I am not acting – in the most common sense – but rather, being myself and talking with my mother on the phone. Seeing it is everything: it creates the kind of irruption my whole schtick is founded on. It causes a break, I think, that affords a deluge of questions about reality, representation, mortality, all of the cornerstones of my work.

What’s lost or gained in that process of digital transformation?

That’s such a huge question. To be simple and a little cute about it, I’d say that one might gain loss. As in, find and be able to think about certain kinds of loss that might previously have been unavailable.

Do you see yourself as a performer?

Sometimes, yes. I mean, yes. All the time, I suppose. I do really like performing, in the most traditional sense. Like, being on stage. Reading. Acting.

How did your mother feel about taking part in the work?

She was thrilled.

The piece takes the format of an interview which you’ve also used in other works such as Us Dead Talk Love. What about this particular structure interests you?

It’s a way to speak that’s naturally expository, so I can have words without them feeling odd non-diegetic? I think that’s right. ‘Us Dead Talk Love’ was kind of billed as an interview, but it was just me splitting myself in order to answer myself, I think. It’s a while ago. I like thinking of an interview as a performance, too. The opportunity to construct and divulge and withhold, all of that. It’s a documentary mode, too, which helps heighten the artifice and its heresy?

How do the text-based artworks interact with or feed into the video works in the exhibition?

The texts are mainly lists machine-embroidered on to huge patchworks of used linen in shades of off-white, to disappear against their ground. They’re almost completely illegible, more pattern than readable text. Long lines of lists, begun appropriated from a couple of historic sources – Artaud and Sei Shonagon – and an alphabetisation of my father’s cancer diary. The lists were *completed* by an artificial intelligence. Each element either reiterates, appends or scuppers its equivalent in the video. The role of the computer – the role of algorithmic processing in the list, the digital, the artificial intelligence. Illegibility as analogue for various disconnects and eternally unspoken things. The AI’s writing is another kind of impersonation of life.

What typically comes first for you writing or visual material? Does one come more easily to you than the other?

Writing’s the most expedient thing to me, and most images start off as a certain turn of phrase, I think. I’m no good at preparatory work. There’s no sketchbooks or notebooks. Or rather, there are, but I don’t look at them. They’re more or less solely performative, or a way to go through a kind of ritual of work. Something like that. I tend to make the final thing first, and sort of simultaneously, once all the pieces are ready.

How much do you plan what you’re going to create?

Not so much, increasingly. The setup is usually a kind of setting of the scene to allow as much improvisation as possible. Which relates directly to what I want to make, as regards to a weird faking of imminence, I suppose. Like, modelling accident?

Do you think about how an audience might react when you’re making a work?

A little bit, insofar as I want the work to be fantastic.

What’s next for you?

I think a new book of writing is coming soon. A play I’m writing and directing with the poet Steven Zultanski will open at Revolver in Copenhagen in March next year. I’ve a show scheduled for Tate Britain in a few years. A feature film?

“Ed Atkins: Get Life/Love’s Work” runs until 3 October 2021 at New Museum, New York. For more information, visit: newmuseum.org

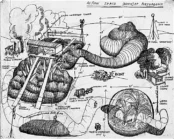

Featured Image: Ed Atkins, The Worm, 2021 (production still). Video projection with sound, 12:40 min. Courtesy the artist. Commissioned and produced by the New Museum and Nokia Bell Labs / Experiments in Art and Technologies

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.