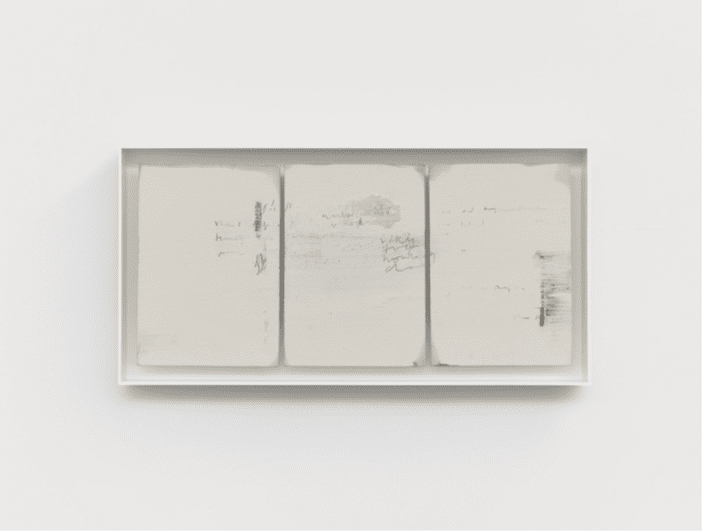

Best known for his large-scale installations of ceramic vessels, Edmund de Waal’s artistic practice centres around a deep engagement with the complex material qualities and histories of porcelain or “white gold”.

Following the publication of our latest issue Materials II, Millie Walton shares the transcript of her conversation with the artist which informed her essay The Infinite Gestures of Porcelain: Edmund de Waal.

When did you first start working with porcelain?

I’ve been making pots since my childhood, but I didn’t actually start working with porcelain until I was in my twenties after I’d done lots and lots of work with other kinds of clay. My first encounter with porcelain was interesting because it felt almost like going back to the beginning. It’s not an easy material to work with, but what it did provide was a wonderful, exploratory feeling and because I couldn’t make things that were perfect yet, play became a very important element.

Porcelain also led me to all these very interesting connections: the profound connection with the ceramics of China, Japan and Korea, the work of [Kazimir Severinovich] Malevich and [Piet] Mondrian. But at the heart of it was simply this lovely, complicated, sticky, plastic material, which didn’t feel anything like the granular, gritty kinds of clay that I’d been working with before.

What makes it a difficult material to work with?

It’s a strange material in that you have to work very quickly otherwise it collapses, which means you have to be decisive in your movements. It also stains easily and picks up the dirt from your hands. It’s got all these strange, wonderful qualities which make it a kind of threshold between different kinds of experiences. For example, it is clay but it’s also like glass because it’s translucent, and it’s very light so in some ways it’s closer to paper than it is to ceramic.

Many of your installations and exhibitions seem to emphasise porcelain’s whiteness. What’s your relationship to that particular kind of white?

Well, it’s not completely benevolent and in many ways, it isn’t an aesthetic of simplicity or an aesthetic of purity. It’s much more complicated than that. I wrote a whole book The White Road about my relationship to the material and its whiteness. The epigraph is from Moby Dick: “What is this thing of whiteness?” And so, I guess it’s really a kind of questioning of whiteness. Whiteness can be a beginning, it can be a sense of possibility, but it can also be erasure, a kind of rubbing out, and it can be dangerous – as we know, the politics of whiteness is truly horrific. In the book, I talk about the cost of that quest for purity. For me, it’s anything but neutral: it’s a whole arena of possibilities and histories.

Speaking of porcelain’s history, are any artists or makers, or perhaps objects that you’ve collected over the years that have been particularly influential on your practice?

[Picks up a pot] This is very early Meissen porcelain – the first experimental porcelain – which was made in the West in about 1715. At that point, they could hardly understand how to make porcelain and it’s an incredibly fragile piece so it’s quite extraordinary it survived. I also have a teapot made by Malevich in 1922 when he was doing revolutionary things with porcelain. He radically stripped away all decoration and it can’t be used – it’s an object that is entirely a manifesto, which I love. These objects are very talismanic.

Each time you return to your studio and sit at the wheel, is it important for you to find a sense of newness in the repetition?

The great thing about repetition is that it’s endlessly renewing. Each return is slightly different. That said, this last year, I’ve been making huge pots and vast dishes which I haven’t made for years so that’s about working out how to make things all over again. It is a return, but to something I thought I’d left behind. Repetition does interest me a lot. It’s why I’m drawn to people like Agnes Martin who make things in a serial way.

What made you decide to start working at a large scale?

It was during lockdown and feeling a deep, visceral need to make objects that weren’t part of an installation, but objects to hold, to put your hands on, to touch. I didn’t know it was going to happen until it happened.

That’s interesting because many of your previous works also bear visible marks of imperfection or their making. Do you think this invites the viewer to more readily imagine their tactility even if they’re unable to actually touch or hold the objects?

Well, you read a lot of touch optically. For example, you wouldn’t dream of rubbing your hands over a Frank Auerbach painting to feel the surface, but you absolutely get the depth, velocity and tactility of his mark-making. I think you read mark-making and weight with your eyes. So, I’m interested in both touch and looking but not touching. I did an exhibition of the lockdown pots called some winter pots, which was all about objects to hold so it’s not that everything [I make] has to be in a vitrine.

Do you think we learn how to read surfaces and weight from looking at objects?

Yes, I think so. In our culture, we have a very diminished tactile, sensory world. The objects that we use every day are often very homogenised – factory made, stackable or throwaway, like coffee cups from the cafe on the corner – whereas, in other cultures, vessels are regarded in a totally different way, they’re made in more diverse ways and their uses are so much richer.

Can you talk a bit about your thinking around the relationship between object and space in terms of how you assemble your installations? Is the composition planned before you make the objects?

It’s different every time, but it never ends up being what I planned, which is similar to writing. For example, I might have a shape in my head of this beautiful, lucid text that I’m going to write, but the experience of writing changes the propulsive nature of the text. Similarly, I might order a vitrine, make some pots and glaze them but when I start putting them together, I realise that it’s all wrong and I have to start again because maybe, it’s got to have more space or more vessels, or it’s actually about marble, gold and porcelain coming together.

How often do you throw away objects that you’ve made?

Oh, all the time, but I do keep some things and then, they become part of something else.

This interview was carried out in May 2021.

Featured Image: Edmund de Waal, the interdicted land. © Edmund de Waal. Photo by Mike Bruce. Courtesy Gagosian.

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.