Ellen Carey came of age artistically in the 1980s, when photography was moving away from representational and reportorial images into increasingly experimental realms.

Over the years, she has used light to search for beauty in the abstract, embracing photography’s uncanny characteristics, its ability to capture chance, while also reflecting on the performative nature of the picture-making process.

Here, Trebuchet speaks to Carey about the evolution of her practice, periods of struggle and her love of Polaroid.

You refer to yourself as a ‘lens-based artist’ rather than a photographer. Why is that?

Nowadays, anyone with an iPhone can call themselves a photographer, but in the past, where did one go for a fine arts education in the visual arts, in photography? Andy Grundberg’s new book How Photography Became Contemporary Art documents this revolution from Pop to Digital. The term lens-based artist signals my choice to use photography as an art form, to see beyond what is in front of the lens, looking through it and at it differently as a photographic object, at what was made and how it was made, and emphasising its materiality. The word ‘photography’ literally means “drawing with light”: in Greek phōs means light, graphis is drawing. All of my concepts begin with light and its variants such as shadow, silhouette and reflection.

What drew you to photography as an artistic tool?

My parents gave me a Polaroid camera in high school, but I really became interested in photography in undergraduate school at Kansas City Art Institute, where I studied from 1971 until 1975. We had short-term, workshop-like rotations through the departments, in my freshman year — throwing clay, glass blowing, painting, drawing, sculpture — but to be honest, it seemed hopeless. I’d look at a blank canvas and it would just stare back at me. It was an existential crisis of some magnitude. I knew I was visual, but how was I visual, what materials to use? But when I went into the darkroom, an apt metaphor perhaps for where I was, very much in the dark, that was it for me: I fell in love with everything about photography. I would work 10-15 hour days and it was very freeing. I knew from then on that my life would be here, in photography with a focus on light.

When I read about Talbot I discovered he also couldn’t draw — I think that’s often the case with photographers —we can’t draw or paint. We have ideas though! When at KCAI, across the street was The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, I would spend hours looking at their collection. I also worked as a model at Hallmark Cards, which was founded in Kansas City, one of my jobs, to put myself through school. I learnt a lot from being on the other side of the camera, and really, I was falling in love with art, with museums, and nature.

When did you first begin experimenting with photograms? And how do they fit into your contemporary practice?

My (re)introduction to photograms parallels a period of struggle. To give you some context, I moved from Kansas City Art Institute to study at The State University at Buffalo. While I was there, I did museum studies in art history, working with many of their curators, and later as a curatorial assistant to the visionary contemporary curator Linda Cathcart at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (AKAG) where I had access to their great collection. The Buffalo avant-garde is well documented by now, back then it was tremendous!

After my MFA, I got a CAPS grant and moved in 1979 to New York City. New York was really tough in the late 1970s and early 1980s (documented in films like Boom for Real about Jean-Michel Basquiat and the docudrama on Robert Mapplethorpe) and I was very, very poor. My father had also died suddenly right before I moved so I was also in a state of mourning, but I did the best I could. I ran every day on the West Side highway and I had three jobs, which I still do! Then, I started teaching at The International Center of Photography. Linda introduced me to Marcia Tucker, who left the Whitney Museum of American Art to open The New Museum and I met Allan Schwartzman, who very kindly gave me a job documenting Marcia’s exhibitions. When Linda came to town, she took me to all the galleries and I met everyone — dealers, artists, collectors, photographers. I went from one avant-garde in Buffalo to another, in New York City, and everything you read about that time is true!

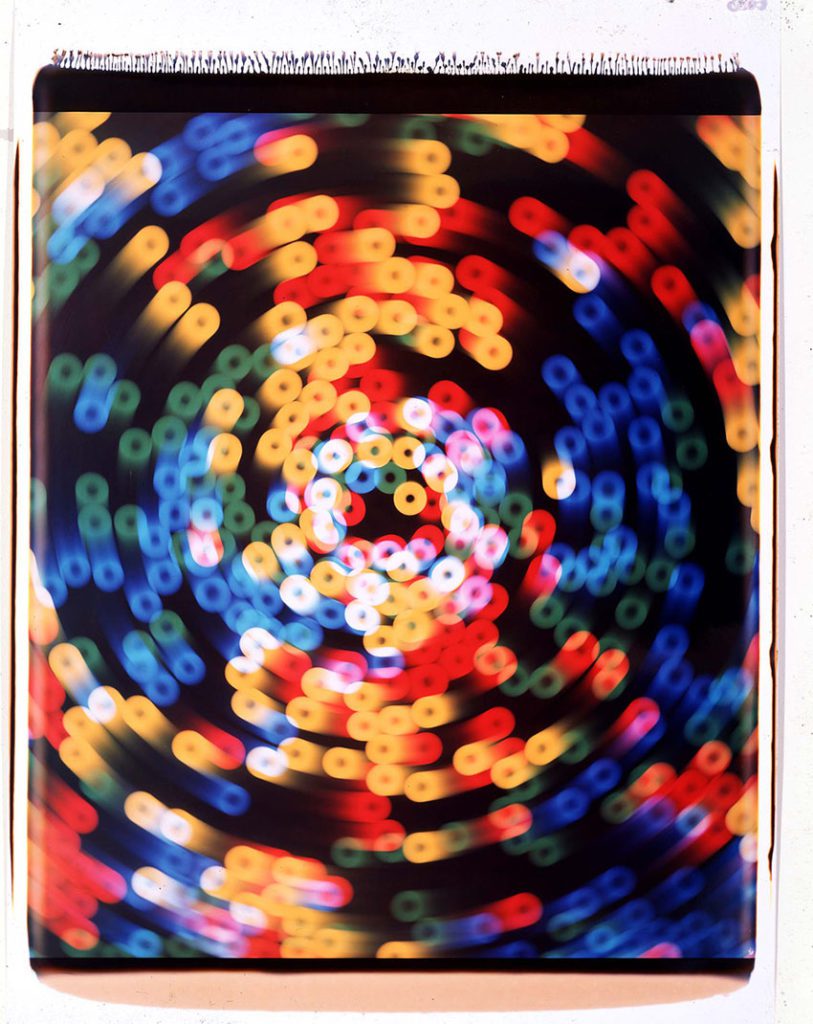

In 1983, I was invited to the Polaroid Artist Support Program, originally in Boston, then moving to SoHo, lower Broadway, right around the corner from my tenement in Little Italy — by then I had a studio in SoHo, across the street from Donald Judd! Finding the physical beauty of Polaroid, plus working in combination with that unique material in my experiments, its luminosity literally “glowed” for me. I left the expressionist mark-making and over-painting behind, the frame became full, richer in tone and variety and visually powerful. I found my métier, my materials and beauty. All my ideas came into focus. I was an experimental photographer, lens-based, a contemporary American artist, who was a woman, with a keen interest in colour in art, technology and Polaroid.

By then, the AIDS epidemic had fully arrived and with it the parallel onslaught of drugs, homelessness, death and destruction and the crash of 1987. It was a wild, scary and tumbling time. It was here, at this time, I think my search for something else began. Commuting back and forth, between the chaos and density of NYC and the nature of Connecticut, I was becoming more visually awake, seeing the different kinds of beauty, the contrast between chaos and order, symmetry and asymmetry, light versus dark, shadow with outline and I had more time to reflect, read and draw.

With the crash of 1987, the Polaroid Artist Support Program ended. So, I went back into the black and white darkroom, and started looking once again at the history of photography via Talbot and Anna [Atkins], researching the photogram as the light sensitive object. It was a very hot summer, I was doing a lot of printing, nothing worked, and I felt lost again. Then I started to ask myself: what is an abstract photograph? My influences came from Surrealism, Dada and Abstract Expressionism, movements which are underscored by non-traditional approaches to making art. After many, many hours of working, plus lots of failures, I got one image, which pointed the way forward.

You’ve said before that your work represents the absence of a picture “sign”. Can you talk a bit more about this and how it relates to your artistic aims?

The picture sign absented itself in my work around 1996. I had experienced a series of losses in my personal life — two weeks before I moved to New York, my father died suddenly; in 1995 my middle brother died suddenly; then, my mother, diagnosed with a terminal illness, died shortly after my brother, her son. So, in August of ’96, I went to the Polaroid studio and made a series called Family Portrait in a monochrome palette. I was looking at the row of seven glossy positives, empty rectangles, white and black, and in that moment, I had what Freud called an experience of the uncanny, which is the same experience I had when I was looking at my brother in his open coffin, he looked like he was still alive, breathing. To me, the negatives looked like open burial pits.

Photography describes the external world, and my world at that point was indescribable. It was an aporia, a paradox, and that made me reflect on the medium and the concept of a picture sign.

To what extent do you plan your compositions?

I keep a lot of notes, some of which are technical — the kinds of colour gels or films that I use, but there are always elements of surprise. The Mourning Wall, for example, was this huge installation that I made the year before September 11th, 2001. I did the Polaroid session one hot day in New York, installed it in September (2000) and I knew the Polaroid negatives were going to change — the excess chemical fluids were going to crystallize, the water was going evaporate. During the installation of one hundred grey Polaroid negatives, 45 feet wide and fifteen feet high, into a monumental grid, the Polaroid negatives slowly dripped into one another. One critic said, “it looks like the Mourning Wall is crying”, which it did.

Do you think your approach to art-making has changed over the years?

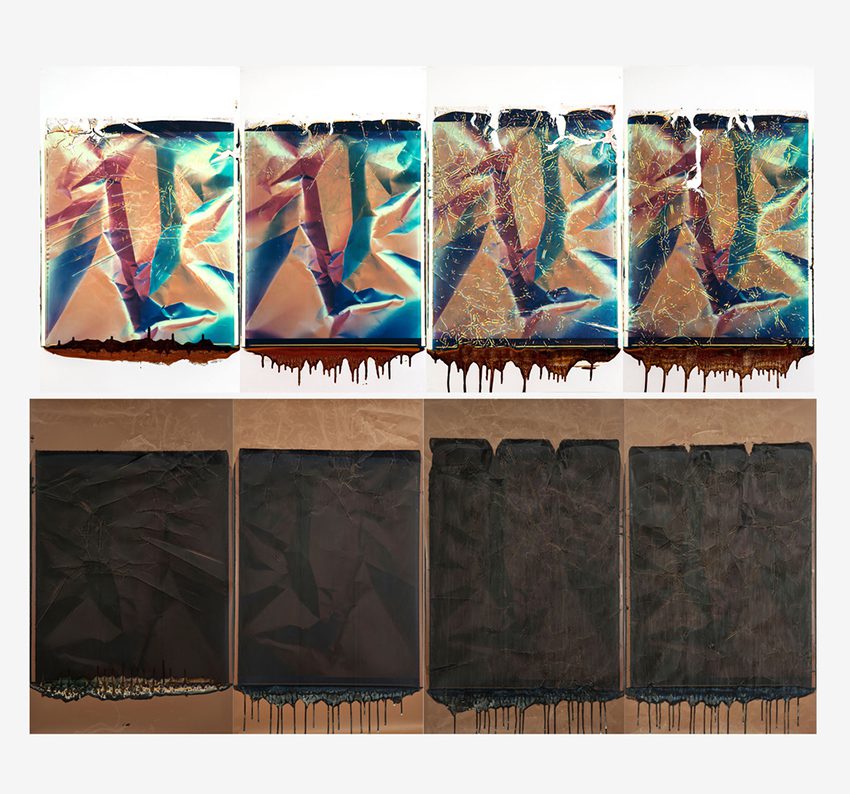

Yes, there is a kaleidoscope of experiences that integrate across my for four Cs: concept, context, content and citation. Change came when I recently partnered Polaroid instant technology and the photogram process in the creation of something unique and new in my Polaroid 20 X 24 series Crush & Pull (2018). This highlights the dawn of photography, underscoring the negative’s importance, both as object and metaphor, it delivers a Polaroid photogram, with new photographic object in several variations: Crush & Pull & Rollback and/or Crush & Ding, the latest is Crush & Pull with Rollbacks & Penlight.

Do you follow a particular working routine?

Good question. My best creative time seems to be from 1pm to 7pm, I usually start testing late morning. I have done various time tests, to see when/where my creative energy exists and this is my window. If I’m printing and nothing’s happening, I stop wasting paper, always making careful notes about the month and day, f# stop numbers, exposure times, and so forth. When I’m in the colour darkroom, complete silence is mandatory. I need silence, in the dark, for concentration, total darkness in ‘crushing’ the Polaroid negative, so they do overlap. Sleep is important – it is a full-on working day, sometimes it goes on into the early evening. I listen to music, make notes, and am happy if I get one good image!

What’s next for you?

I’ve just finished an exciting collaboration with Dunhill and I have a solo show coming up in Paris in April/May next year with the new series of Crush & Pull and those variations, which I made during the pandemic. Galerie Miranda and I have already done a preliminary selection of diptychs and triptychs as well as four-panel and six-panel works.

I am looking forward to getting back into the darkroom again. I have new ideas I need to explore. I did some collage pieces early on in the pandemic — not sure how successful they were, another idea that’s percolating. I also go back to teaching in the fall, after a year off, and I’d like to continue with my curatorial project Women in Colour: Anna Atkins, Colour Photography and Those Struck by Light which re-examines the role of women artists in colour photography. We did a group exhibition at the Rubber Factory in 2017 in NYC that included Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons, Carrie Mae Weems, and Meghann Riepenhoff, all fantastic, and another group show in Paris in 2019. I’d love to get the exhibition presented in England, somewhere in the future with a book/panel/lecture. That would be fantastic, and the time is perfect for it! I have been working on this research for close to a decade now, with the link to the DNA tetrachromacy gene, on women and colour, it is a scientific fact, and reframes the 50 year-old question by Linda Nochlin: “Where are all the great women artists?” To which I say, “We are here, Linda, in photography, in colour!”

Find out more about Ellen Carey’s practice: ellencareyphotography.com

Featured Image: Crush & Ding, 2019, Ellen Carey. Collection of the Artist, Courtesy Galerie Miranda, Paris, France

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.