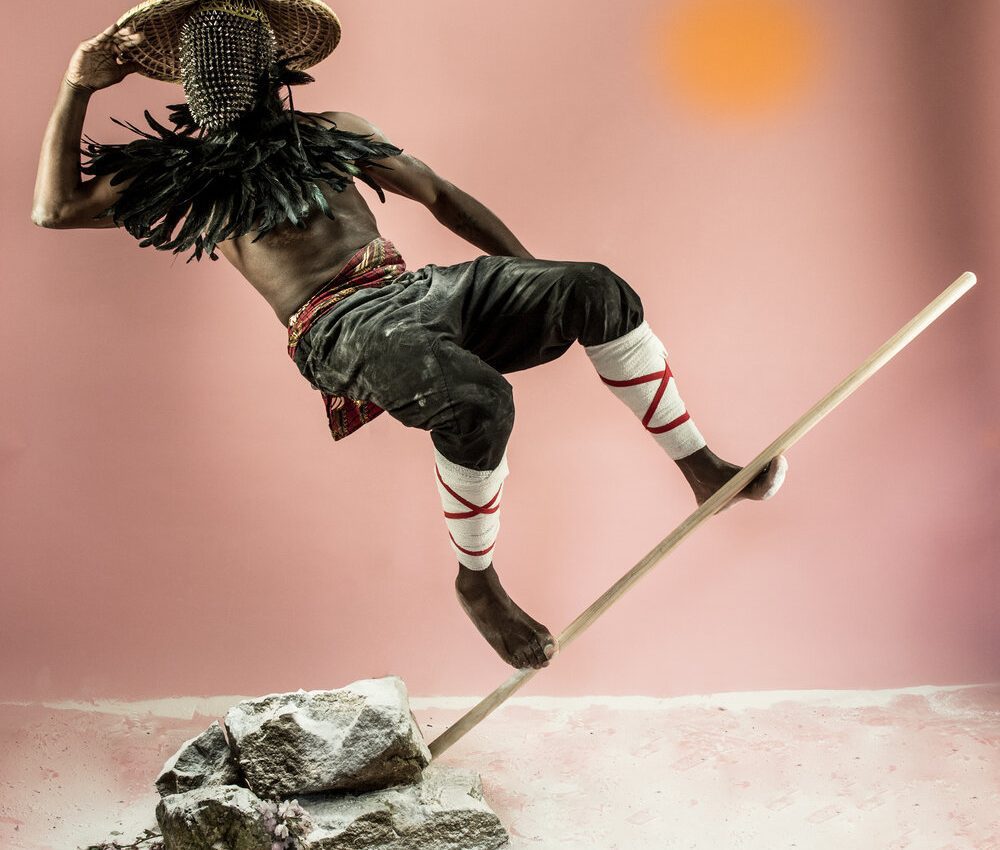

The photographic poems of Manchester artist Benji Reid present us with a surreal world where culture, choreography and photography combine to tell us metropolitan stories of longing and release, subverting the aspirational and acquisitive culture that emblazons our commercial centres. Humans soar, float, and form classical shapes as they escape commonplace settings. There is a conceit in much of the art of a certain western 1950s introspective bokeh; the figures may depict universal human emotion and yet they seem caught in the repose of a post-war monoculture. The art of our commercial salons often reflects a conservative world view of nostalgic transgression, Brideshead homosexuality and the chinoed rebellion of the Beats. The problem is the contemporary world is already a layered proposition painted so thick it mutes many of the artists’ messages. It is a rare talent that manages to portray the 2020 world without falling into the media-driven tropes that would hijack the artist’s meaning.

“My mind’s eye is always drawn towards the dramatic, the incongruous that speaks of the many worlds that reside within us, which in turn sheds light on our humanity.” – Benji Reid

Benji Reid draws on over 30 years of experience as a performer and creative director to stage his shots and since 2012 has exhibited his photography in MoCADA (Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts), New York, as part of the 2019 exhibition Styles of Resistance: From the Corner to the Catwalk. In 2019 his work was also included in the highly acclaimed exhibition Get Up, Stand Up Now, curated by Zak Ové at Somerset House. 2020 sees Reid pairing with October Gallery in London to stage what is perhaps the most complete summation of his work to date. While October Gallery has been known of late for showing international artists, in some respects the Benji Reid show will see the space returning to its avant-garde roots and gives Reid the opportunity to show his choreo-photolist work to a London audience.

“I am a choreo-photolist—where theatricality, choreography and photography meet in a single or series of images.” – Benji Reid

Reid uses everyday objects and elevates them. When his work is successful we are able to see those thick symbols as unique and under the control of our perception. Reid calls this process reframing, where an object is recontextualised but not reimagined. The hip-hop shoe is still the hip-hop shoe; it harbours all the ‘urban’ tropes, but those tropes themselves are heightened, perhaps even sanctified. Which is to say, removed from historical reality and placed into the fantastic realm of ideas. Tellingly, many of his works are solitary. These are introspective works, less about tangible future fantasies than stencilled outlines of personal growth. They are described as image poems but could just as easily be described as tools of ascension. Reid wants us to imagine that we can imagine; mature and joyous fantasies are empowering tickets to internal possibilities rather than quick fixes. In his use of symbols he has directly transformed our indirect world.

Catching this artist at an important time of his career when his approach and execution feels particularly fresh and potent, Trebuchet spoke to Reid about how he makes these impressive poems.

How do you approach the uncanny, weird or surreal? Does your work play with psychological frame of the physical?

Absolutely. My first understanding about the work I’m making is that. How do I reframe my body? How do I reframe what blackness is? How do I start a conversation that is contrary to a lot of the images we are fed around black masculinity? And how do I offer the body in a space that is unique? How do I get you to look under the skin? Because my idea is, could I take pictures of moods, of emotions, of feelings? But not make it so ephemeral, not make it so mystifying, but ask how you look underneath it. My proposition is that I want to be this middle-aged black man floating on a cloud. And then I’m saying, ‘Here are some of the symbols I’m playing with. Now, what are the gaps in-between this and what have you known?’ This is what I’m interested in doing.

Speaking about symbols, I notice you’re working with ideas like connections, chairs, afro symbolism, gravity, space, aspects of diaspora, emigration, immigration, and travel. Is there a baseline for your perspective on these symbols?

I could talk about the African diaspora which is such a beautiful theme or even about afrofuturism. But here’s something else I offer: the proposition of the African body being in a future space, a reimagined space, all the places out of the mundane. One of the important questions is how do we stop ourselves being so earthbound? My whole idea is about space and futures, where we’re going… this is where I see ourselves as free beings operating in another dimension, another time. This is the reason why weightlessness constantly comes up. We don’t have to be bound by the here and now. We can be bound by our futuristic imagination. So that is part of a political statement of not being forced to be the rapper with the big gold chain, or struggling on the floor going, ‘No, wait a minute.’ I’m operating outside of these bounds of norm. That’s why I’m talking about reframing.

For instance, we take the classic Superstar shell toe that has been worn by B-Boys since the 60s and 70s, but then we offer a reimagining where that shoe can sit in space. So I’m still speaking to the B-Boys, the hip-hoppers, but I’m also going, ‘Where else can we be? Where else can we occupy space?’ They’re part of the tropes that I keep pulling on because I’m not abandoning them, I’m just reframing them. I feel a lot of my works are like one-image poems, that they have all these things we recognise but they’ve slightly been rejigged to say something else about our humanity…

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle