[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]S[/dropcap]eoul has fast become a mecca for plastic surgery, complete with an entire district filled with nothing but cosmetic surgery clinics where roughly 7.5 million have been served.

While statistics suggest that one out of every twenty women living in the US have opted for a minimum of one cosmetic procedure, the ratio in Korea is much higher: one in five, to be exact.

This is due in part because surgeons in Seoul charge a lot less for their services. Take for instance the cost for rhinoplasty. In the US, surgeons charge approximately $8,000 whereas many in Seoul charge up to 75 percent less. While accessibility is a contributing incentive here, the underlying motivation amongst most who opt to undergo elective surgery, however, comes from the prevailing assumption that western features are indicators of beauty.

Born in South Korea, Chong-il Woo moved to the United States in 1979 to study fine art. After graduating from the Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, Oregon, Woo’s eye for the female form quickly earned him recognition as an accomplished fashion photographer. And, before long, Woo began contributing regularly to publications such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar.

Over time, Woo began to miss his homeland more and more. Although he enjoyed his life in the States, he knew that he couldn’t recreate the familiarity of living within a culture with which he once felt a part and thus made the difficult decision to return home after spending approximately two decades abroad.

When Woo returned to Korea, he was faced with a disheartening reality to which Thomas Wolff’s famous five word phrase is more than applicable: “You can’t go home again.” Instead of returning to what he remembered as a country defined by its historically rich culture, Woo found himself faced with a pronounced change in the physical features of an extraordinary number of native-born Koreans.

Paying witness to a growing majority of women who continually seek out surgical augmentation in an attempt to have have their jaws narrowed and eyelids doubled, Woo admits that he remains saddened by what appears to be a denial of Korean heritage.

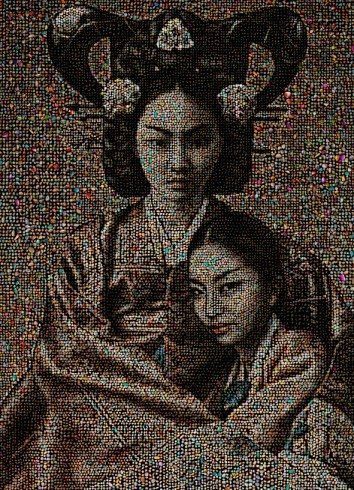

Woo’s reaction, however, was not in vain. Instead, he was inspired to begin what turned into an amazing series of works that won him the Schoeni Prize in 2012. The series, entitled Women of the Joseon Dynasty, combines what Dervla Louoli for The Peninsula describes as Woo’s “flair for photography and passion for art [through his creation] of multi-dimensional portraits of beautiful women from ancient times in an innovative and modern fashion.”

Woo made the choice to base his series on a specific group of women; not only did they live during the longest ruling Confucian dynasty, but they were held in esteem for their unique standing within society. Known as kisaeng, this particular group of women had been officially sanctioned by the government of the Joseon Dynasty to work as courtesans. Although indebted into lives rooted in servitude, these women weren’t only provided with a well rounded education, grounded in literature, music, and art, but they had the rare freedom to move about society.

only did they live during the longest ruling Confucian dynasty, but they were held in esteem for their unique standing within society. Known as kisaeng, this particular group of women had been officially sanctioned by the government of the Joseon Dynasty to work as courtesans. Although indebted into lives rooted in servitude, these women weren’t only provided with a well rounded education, grounded in literature, music, and art, but they had the rare freedom to move about society.

By aiming his lens upon this particular group of women, Woo has shed light upon the many facets that comprise true beauty. Not only are Woo’s subjects physically striking, but the historical significance of their roles within Korean history demonstrates how integral one’s culture is to one’s essence of being.

Even more, the process by which Woo produced each of his pieces for this particular series proves utterly mesmerizing. After photographing his subjects, each of whom Woo outfitted in authentic garb representative of the Joseon Dynasty, he then digitally replicated his subjects’ images with mosaic-like patchworks of pebbles that he had photographed previously and then stored in a digital library for this particular project.

400 hours is what it took Woo to produce just one of his impressive pieces that comprise this latest series. But in doing so, Woo has produced a phenomenal body of work that doesn’t just showcase the inherent physical beauty of the natural Korean woman, but he has illustrated just how integral one’s heritage is to any one individual’s overall allure.