[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he vast majority of Portuguese in Portugal are fado deniers. They know it but deny ever seeing its true face. They say they don’t feel it because fado has to be felt to be known. If they know it and they feel it, they’ll have to say they like it. Then they’ll love it. So they deny they feel it. It’s complicated. Outside of Portugal, it is a very different matter. From Japan to France to the USA, fado is known and it is felt, and not only by the Portuguese diaspora.

More of that later.

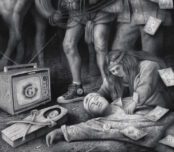

Recent history in Portugal has meant that particularly those who lived there during the Salazar and subsequent fascist regimes, see fado as something to disassociate themselves from. It reminds them of darker times, of freedom curtailed… and of fear. Ironically, Salazar himself hated it and tried to control and censor the potentially subversive song by also using its greatest exponent at the time in an attempt to associate himself ‘with the people’, but with only partial success. He didn’t trust fado. The feeling was mutual. It took until the early 80s for some of the Portuguese people to begin to forgive fado a little and accept that it was even there.

An art form so uniquely Portuguese should, in fact, be revered and celebrated in the country rather than ridiculed. That process has now perhaps properly begun as witnessed through its embracing by a younger and more vibrant generation of fadistas (both singers and instrumentalists) who despite being able to change and reformulate it, continue to fundamentally write and perform it in a traditional way. It ain’t broke, so they’re not fixing it. This is music for the people by the people. These are stories of neighbourhood life and lust and loss and pain. A great deal of pain.

“Who feels it, knows it” – Bob Marley

Fado has a rich history, perhaps going back even further to before the mid 19th century, and remaining fundamentally unchanged since that time. Where technology was embraced by the sister music of the blues and hip-hop, fado musicians have continued to embrace only the Portuguese guitar and the nylon acoustic. No Mr Boombastic here. This is because it is a humble and honest and direct music, where the song is everything. Where the lyrics set the scene, tell the story, intertwine with the chords and the structure of the instrumental and deliver its final blow. That blow is saudade. Like the Portuguese guitar, like fado itself, the word saudade is uniquely Portuguese. Portuguese uniquely. All Portuguese say they know what saudade is but not all Portuguese FEEL saudade. And not many Portuguese can articulate what saudade is in another language. Fado is able to do that for them, in an incisive and compelling way that simply no other music in the world can do. Fado is the auditory manifestation of saudade.

Later.

I am a music producer, composer and songwriter, lucky enough to be working in London with corporate record companies and major TV ad agencies. I was born in Farnham Common, Buckinghamshire, to Portuguese parents. I spoke only Portuguese until I went to school at five years old. Those were the days when being an emigrante wasn’t something that people seemed to be ashamed of. They were proud of it in fact, and their families back home were proud of it too. The denial comes full circle.

It was my parents’ pride that first exposed me to fado as a young child. In those days, Portugal was rarely on TV in England. It was a place where only the rich British visited and played golf, so it had not yet been featured on late-night reality shows about drinking and drug-taking in coastal clubs, as is so often the case nowadays. This meant that at every rare appearance of anything remotely Portuguese on screen, I was put in front of it, usually in my pyjamas, whilst the TV article was narrated over a bed of fado music. It took me a long while to understand why my parents would go silent and start crying. I was four years old… I didn’t feel it, so I didn’t know it. The first time I really felt it, I knew it. I was eight years old. Saudades.

That’s the real reason people in Portugal don’t like fado. They don’t feel saudade. They don’t know what it’s like to be in a place where you have a funny name, it’s cold, it’s raining, people don’t speak your language, the food is bad, and you’re called names for being a foreigner. This was my experience as a child and growing up with parents whose pride was only made stronger by their difficult experiences. Whose difficult experience turned into saudade. With the recent growth in young emigration, things will change for some more Portuguese and they will find a new and fervent appreciation of fado. It won’t be overnight. It will take time and be directly proportionate to the amount of time they spend away and subsequent longing they have. I look forward to the next time I see a Mariza or an Ana Moura play London, somewhere like the Union Chapel in Islington or the South Bank, and seeing the tugas with their new London friends holding back the tears and failing miserably. They’ll admit defeat. They’ll be proud. And so will I.

Only from loneliness or from suffering will you come to know what saudade is, and it’s precisely for this reason that fado is so important to the Portuguese who are far away from their families and their beloved country. From the days of the sailors during the Discoveries right up until today, fado is melancholic and nostalgic. Just like the Portuguese. They dovetail together and make a perfect fit. It’s like they were made for one another. Who feels it, knows it.

I am Portuguese. I am proud. I have saudades. And I love fado.

Danny de Matos (aka Lisbon Kid) is an alternative electronica producer, writer and DJ. He also guest lectures at Point Blank, London’s pre-eminent electronic music school. He is Portuguese, married to Lesley, a father to Lúcia, and a fan of Setubal region red wine.