[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]H[/dropcap]istory, as Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus put it, ‘is a nightmare from which I’m trying to awake’.

Living through it is no less of a challenge, but at least affords the protagonist some sort of mobility. Such were the attempts of artist Wolfgang Paalen to escape history and reshape experience from the unlikely location of Mexico City during the Second World War.

Paalen wasn’t alone. From the outbreak of hostilities, artists based in Europe were faced with the decision to contribute to the war effort of their home (or adopted) countries in the conventional way, or to flee, and make their contribution through their art. Mexico City drew a cluster, in large part due to Frida Kahlo’s invitation, endorsement and hospitality.

Hindsight allows us something of a sneer, brandishing our imaginary white feathers with the confidence of those who have never faced world war (or if we did, were too young to make decisions as it played out). Given that the focus of 1930s European art was Paris, the option of heroic resistance from a European theatre of operations was restricted at any rate.

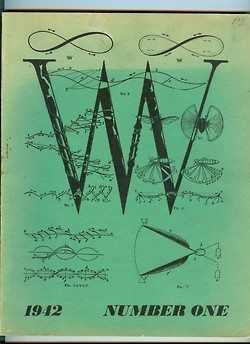

The leafy suburbs of a Mexico City as yet unsullied by the air pollution and overpopulation of the post-war era offered a triple whammy of advantages to artists: safe, bathed in abundant light, and above all, cheap. The city proved a nexus of artistic, musical and bohemian types, each with their own personal, professional, and often manifesto-stated motivations to follow (up to and including the exiled Bolshevik, Leon Trotsky). Wolfgang Paalen’s approach was to found and publish a periodical, showcasing the works and methodology of his own favoured group of Mexico-based artists. The imprint, entitled DYN, chronicled an art movement Paalen struggled to define, exactly, but which coexisted grudgingly with the competing movements of the time. Paalen, on his part at least, felt a fierce rivalry with the surrealist movement, particularly André Breton, and Breton’s New-York-based periodical: VVV.

That rivalry seems to have spurred Paalen throughout the lifespan of DYN. Strategies familiar to the modern blogger will be familiar in Paalen’s inclusion of established artists in the pages of the magazine (pitched as if it were DYN recognising their importance, rather than they who were lending credibility to the imprint), and in his practice of writing under pseudonym in the hopes of seeming to lead an artistic movement with more disciples than was actually the case.

Achieving prominence and dominance in the visual arts has long been an exercise in narrative-control, self-promotion and marketing. Ultimately, the artist is in the position where he must make a decision; should the demands of the publicity machine influence the nature of the artworks produced, or should the opposite apply? Grand gestures such as publicly taking one’s lobster for a walk or declaring mass murder as the ultimate expression of an artistic movement (both associated with the surrealists) do not occur in a vacuum of publicity. The degree to which notoriety-courting is the primary motivation for such stunts is subject to interpretation, and depends on how cynical the observer is feeling on any given day, but a little public outrage rarely harmed an artist (with the possible exception of Caravaggio).

Paalen, though, played a poor media game. And yet, his credentials as a tortured artist, for what little those are worth, were exemplary. Dead by his own hand in his mid-forties , doomed to the shadows by the brighter light of lesser talents, driven to ascetic privation in a log cabin in the Canadian wilderness, where he grew wild-eyed, hairy, and learned the ways of indigenous peoples… the screenplay writes itself. But such traits do not bend well to the intensely social pursuit of producing a magazine. Paalen was no Frank Dunphy or Ezra Pound, and while his editorial vision was as exacting as his artistic intent, it takes a whole lot more schmooze to launch a glossy than that.

That said, DYN traces a coherent train of thought in Paalen’s move away from surrealism towards an all-encompassing aesthetic of science and art. The rumours of atomic bomb-building from 1942 onwards, as well as new work on wave theory being published and presented by Erwin Schrödinger, offered Paalen the basis for a personal manifesto based on new modes of thought.

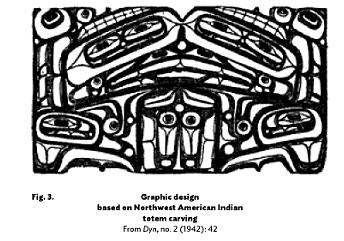

To claim this as exclusively Paalen’s realisation would be misleading; Max Ernst’s front cover featuring imagery related to wave theory for the first issue of rival VVV demonstrates that the surrealists were sailing similar tacks, but what Paalen did do was grasp upon the visual vocabulary of pre-Columbian cultures in the Americas, and recognise the totemic art of those peoples as being the expression of cultures which had never compartmentalised art and science, and religion and society.

DYN, especially in the “Amerindian” double issue which comprised issues five and six, made Paalen’s obsession manifest, juxtaposing images of pre-Columbian artworks alongside post-surrealist abstracts. Where it becomes fascinating is in the peripheral details. Paalen rejected the fledgling Mexican state’s use of indigenous artworks. He, correctly, deemed them the sort of nation-building exercises that often demand deeply chauvinistic applications from art and artists, and which rarely accept that it is the very rogue element and inability to parrot a party line that makes artists useful in the long term.

Even within Paalen’s circle, there were mumblings of dissent—Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera seem not to have appreciated having their indigenous art-collector/interpreter roles encroached upon—whilst Octavio Paz had deep and justifiable qualms about venerating cultures (such as the Maya) whose architecture verged on the fascistic, and whose rituals involved mass human sacrifice. These were the 1930s, after all.

What are more interesting are the twists of resistance to a state-endorsed art establishment in wartime Mexico (and which give DYN a legacy beyond what was likely higher in Paalen’s mind at the time: that of burying VVV).

That state-endorsed aesthetic—patriotic depictions of bucolic peasantry, noble in their toil, honest in their simplicity, etc.—will be familiar to readers who have watched or studied any post-colonial nation’s struggle to assert and build a coherent sense of self (and has its purest and often hilarious form in the lyrics of jingoistic national anthems).

DYN rejected the twee appropriation of First Nation visuals as picturesque souvenir fodder and instead seized upon them as a starting point for a scientific/artistic mode of expression. In subverting the photographic aesthetic of Mexican nationalism (typified by the work of Hugo Brehme) with anti-realist photographs referencing folk myth, Paalen perhaps achieved his aim to move beyond surrealism and its driving ethic of dislocating the conscious mind from the more valuable (to them) artistic wellspring of the id.

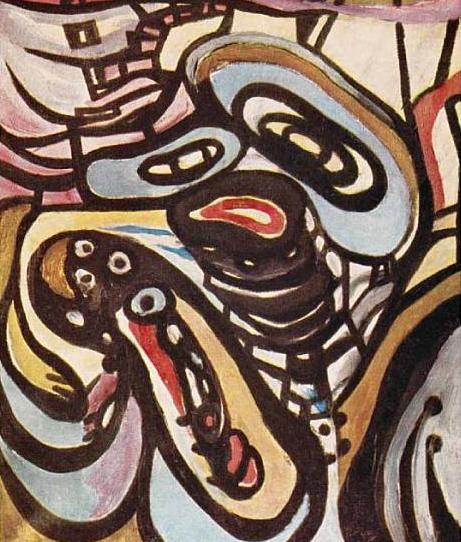

As an artist, his work has been largely overlooked. But as an archetype of the visionary artist, Paalen casts a more imposing shadow on history than most of his contemporaries. Hindsight casts Paalen in the introspective, tortured role; the brightly-burning seeker in the Dean mould rather than the bloated Brando of later surrealism. Crucially, his work is exemplary. Lyrical, haunting; Paalen’s uncovering of the inner mind has none of the wacky sensationalism of Dalí, but plumbs a more credible line to the depths of the collective and individual (un)conscious. His central technique—elaborating upon the random soot marks deposited by a lighted candle smoking beneath the canvas—makes for a purer, more Rorschach expression than the competitively zany parlour-game contrivance of the surrealists’ exquisite corpses.

Paalen was, ultimately, a man more suited to holing up in a cabin in British Columbia to study First Nation totem poles (much as Picasso studied African masks) than to forging a public artistic movement. But, and it is from the selfish point of view of the purist rather than from any empathy for Paalen, his works from 1930s Mexico, despite (or perhaps because of) his abrasive relations with the overshadowing surrealist movement, are his finest.

Conwell, D & Anette, L 2012, Farewell to Surrealism: The Dyn Circle in Mexico, Getty Publications, USA.

Originally Published in Trebuchet 30th April 2013. The text has been revised for the upcoming Trebuchet 8: Contemporary Surrealism

Surrealism surrealism surrealism surrealism

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.