[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]O[/dropcap]nce upon a simpler time, as the Pisces sun began to set, Jean-Louis Lebris de Kérouac caught his first breath in this strange world.

It was in Lowell, Massachusetts. 12th of March 1922. Year of the Dog- a sign of good fortune in the eyes of ancient Chinese. But the Kerouacs only owned cats.

This small city of Lowell, up in the north, was just about to fall off the cliff. By 1922 the jobs were moving south. The Depression was on its way, and even the Happy Days years of America wouldn’t revive it. But Kerouac caught the end. And catalogued it all like a bright-eyed kid in a world that wasn’t too big yet.

The Town And The City, Kerouac’s first published novel begins with a description of Lowell (renamed Galloway in the book):

If at night a man goes out to the woods surrounding Galloway, and stands on a hill, he can see it all there before him in broad panorama: the river coursing slowly in an arc, the mills with their long rows of windows all a-glow, the factory stacks rising higher than the church steeples.

Kerouac wasn’t long for Lowell. He wasn’t long for this life. At the age of forty-seven he was sitting in a rocking chair, in a house he shared with his mother, down in St. Petersburg, FL. A strange climate to settle for a man who’d always had a problem getting comfortable (it’s been written the first thing Kerouac did when he moved to a new house was build a fence around it). On the last day of his life he was still thinking about his youth in Lowell, working on a new novel about his father’s old print shop in the city. Kerouac got up from the rocking chair to puke, which was typical for his mornings, and from that moment he threw up blood until there was none left.

He was brought back to Lowell and buried in Edson Cemetery. Made more iconic by the pilgrimage of Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg to his grave. The most sacred square of dirt to some. The place where Dylan played guitar and Ginsberg read poetry over the bones of a legend. America’s Joyce.

I found Kerouac when everyone else did. In that period of youth when you begin to realize you don’t know yourself at all and you don’t like what they’re telling you to become. And if you’re open to it, the prophets arrive one by one – Salinger, the Velvet Underground, Kerouac. They show you that there are some who need rules, but history only remembers the ones who break them.

On The Road did to me exactly what it was supposed to, at least I thought back then. At sixteen that book screamed for freedom. It made me want to burn my textbooks and go be a writer in California. So I did. But my plan didn’t work. My book wasn’t published. And finally, broke and burnt out, I turned twenty-seven and ended up back at my parents’ house.

I started reading a lot of Kerouac at that time. I found a letter he wrote to a friend where he said, “I’m thirty years old. Sometimes I think the only thing that’s ready to accept me is death. Nothing in life seems to want me or even remember me”.

A whole decade had passed since I’d last read his “masterpiece”. I decided to go back and re-read On The Road. It was like finding a different gospel. What I had initially thought was hope, and confidence and revolution was actually the opposite. Without the lenses of youth I realized what he was actually saying: the Universe does not care about you. I read about lonely roads this time. Decisions that took guts and the chips still didn’t fall right. I was reading about an artist who rolled the dice and knew he was losing.

I read On The Road in an endless loop for the rest of that year. I started to get pieces published and whenever I was asked who my favorite writer was I would say “Kerouac”. They always laughed at this revelation. I found that almost no one else had ever actually read On The Road, and the few that had never read anything else. It’s tragic. Kerouac’s name is synonymous with literature and adventure, and yet, almost no one has actually read him.

Right after I turned twenty-nine I got a book published. For almost fifteen years I had been thinking about what I would do when I held an actual copy of my book. Definitely drugs. Or getting wasted on a good bottle. But I hadn’t earned that yet. I knew I needed to do something for the Gods that were looking down on me. So I called my cousin, Drew A. Ennis. An hour later we were in a car with our girlfriends headed for Massachusetts.

On our way north I read them passages from The Town And The City,

The Merrimac River, broad and placid, flows down to it from the New Hampshire hills, broken at the falls to make frothy havoc on the rocks, foaming on over ancient stone towards a place where the river suddenly swings about in a wide and peaceful basin, moving on now around the flank of the town, on to places known as Lawrence and Haverhill, through a wooded valley, and on to the sea at Plum Island, where the river enters an infinity of waters and is gone.

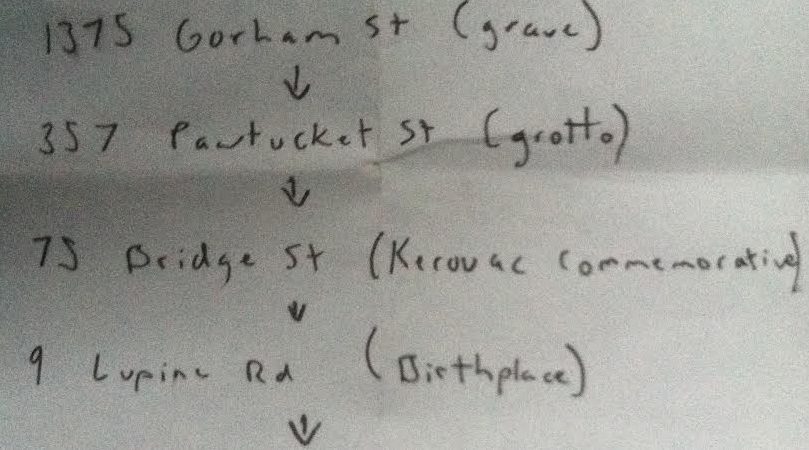

We parked the car at 9 Lupine Drive. The birthplace of Jack Kerouac. A two-story maroon house that looked like every other poor house in New England. There was a For Rent sign on the second-story door, the floor the Kerouac’s rented in March of 1922. On the first floor a big Puerto Rican flag hung in the window.

I got out of the car and went up to the fence in front of the house. A lady walking a dog was watching me.

“Is this Jack Kerouac’s house?” I asked her.

“Who?” She asked.

“Jack Kerouac”.

“I don’t know who lives there”.

I took a picture of the house and got back into the car. I drove us over a high bridge that straddled the Merrimac River. Kerouac had written it perfectly – the river did seem placid from that height. The water did break over rocks and leave frothy havoc. Along the river in both directions were giant mills. Three stories and far as the eye could see. They looked like factories of unimaginable misery. A place where boys punched in and hobbled men punched out.

The Edson Cemetery was on the outside of the city. We drove to the main gate from Gorham Street. Inside the cemetery we were already on 3rd Avenue. We stayed on 3rd until Lincoln Avenue where we made a left. Just after 7th Avenue we parked and got out. Kerouac’s grave was on our right.

A small grave marker, a little bigger than a cinderblock, cut a square deep into the tall grass. It was easy to find. The disciples who had come before us left a memorial of cigarettes. Empty wine bottles. Roses. Rolling papers. Just behind the grave a new monument stood clean. In it was etched a dove and the quote, “the road is life”.

The four of us stood around the grave and smoked a cigarette. Right where Dylan and Ginsburg had paid their last respects.

“There is nothing Kerouac would have hated more than us standing on his grave and telling him he was great”, Drew said.

I took out my book. Drew ripped a drawing from his notebook and lay it on the grave. His girlfriend moved one of the empty beer cans on top of it. I opened my book and flipped around until I found a poem I thought Jack might’ve approved of. I cleared my throat.

“Dear Jack”, I began, “this one is for you”.

I said one word and a machine began roaring. It drowned my voice out. It drowned out everything. We all turned around. A groundskeeper was driving around a giant lawnmower. The wind caught right and the exhaust hit us. It knocked the beer can over and sent Drew’s drawing up into the air. We all watched fly away.

“Nothing is ever good”, Drew said.

I thought about this man Kerouac. Who so desperately wanted to become a legend he lost himself on the climb. All those years in the backs of cars, on the tops of mountains, typing away while the world kept moving. And finally he got his due. But when the royalties and the fans came, he turned on what he had inspired. A whole generation followed his message. But Kerouac never saw them as anything but losers. Spoiled losers. A serious drag on his whole vibe. It wasn’t long before he was spending more time building fences than writing books.

When Kerouac was young he had the heart of buffalo, so eager to see the land before him, and yet by the time he died, he had come full circle, scribbling away an unfinished manuscript about his childhood in Lowell.

We all gave a salute to Kerouac’s headstone. I dropped my book onto the grave. Then we walked back to the car.

The groundskeeper didn’t return our wave on the way out.

Scott Laudati lives in New York with his Boxer, Satine. His collection of poems “Hawaiian Shirts in the Electric Chair” has been published by Kuboa Press. Visit www.ScottLaudati.com for less professionalism and angrier essays.