[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]P[/dropcap]otentially habitble planets within 40 light years! Why in interstellar terms, that’s no more than a quick nip down to the off licence.

Which segues quite nicely with the next, less scientific observation. If these are Trappist planets, surely we should be looking for something with a slightly more… hoppy character than dull old water.

An international team of astronomers used the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope to estimate whether there might be water on the seven earth-sized planets orbiting the nearby dwarf star TRAPPIST-1. The results suggest that the outer planets of the system might still harbour substantial amounts of water. This includes the three planets within the habitable zone of the star, lending further weight to the possibility that they may indeed be habitable.

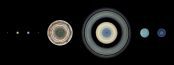

On 22 February 2017 astronomers announced the discovery of seven Earth-sized planets orbiting the ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1, 40 light-years away [1]. This makes TRAPPIST-1 the planetary system with the largest number of Earth-sized planets discovered so far.

Following up on the discovery, an international team of scientists led by the Swiss astronomer Vincent Bourrier from the Observatoire de l’Université de Genève, used the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) on the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope to study the amount of ultraviolet radiation received by the individual planets of the system. “Ultraviolet radiation is an important factor in the atmospheric evolution of planets,” explains Bourrier. “As in our own atmosphere, where ultraviolet sunlight breaks molecules apart, ultraviolet starlight can break water vapour in the atmospheres of exoplanets into hydrogen and oxygen.”

While lower-energy ultraviolet radiation breaks up water molecules — a process called photodissociation — ultraviolet rays with more energy (XUV radiation) and X-rays heat the upper atmosphere of a planet, which allows the products of photodissociation, hydrogen and oxygen, to escape.

As it is very light, hydrogen gas can escape the exoplanets’ atmospheres and be detected around the exoplanets with Hubble, acting as a possible indicator of atmospheric water vapour [2]. The observed amount of ultraviolet radiation emitted by TRAPPIST-1 indeed suggests that the planets could have lost gigantic amounts of water over the course of their history.

This is especially true for the innermost two planets of the system, TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPIST-1c, which receive the largest amount of ultraviolet energy. “Our results indicate that atmospheric escape may play an important role in the evolution of these planets,” summarises Julien de Wit, from MIT, USA, co-author of the study.

The inner planets could have lost more than 20 Earth-oceans-worth of water during the last eight billion years. However, the outer planets of the system — including the planets e, f and g which are in the habitable zone — should have lost much less water, suggesting that they could have retained some on their surfaces [3]. The calculated water loss rates as well as geophysical water release rates also favour the idea that the outermost, more massive planets retain their water. However, with the currently available data and telescopes no final conclusion can be drawn on the water content of the planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1.

“While our results suggest that the outer planets are the best candidates to search for water with the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, they also highlight the need for theoretical studies and complementary observations at all wavelengths to determine the nature of the TRAPPIST-1 planets and their potential habitability,” concludes Bourrier.

Source: ESA/Hubble Information Centre

Image: ESO/N. Bartmann/spaceengine.org

Some of the news that we find inspiring, diverting, wrong or so very right.