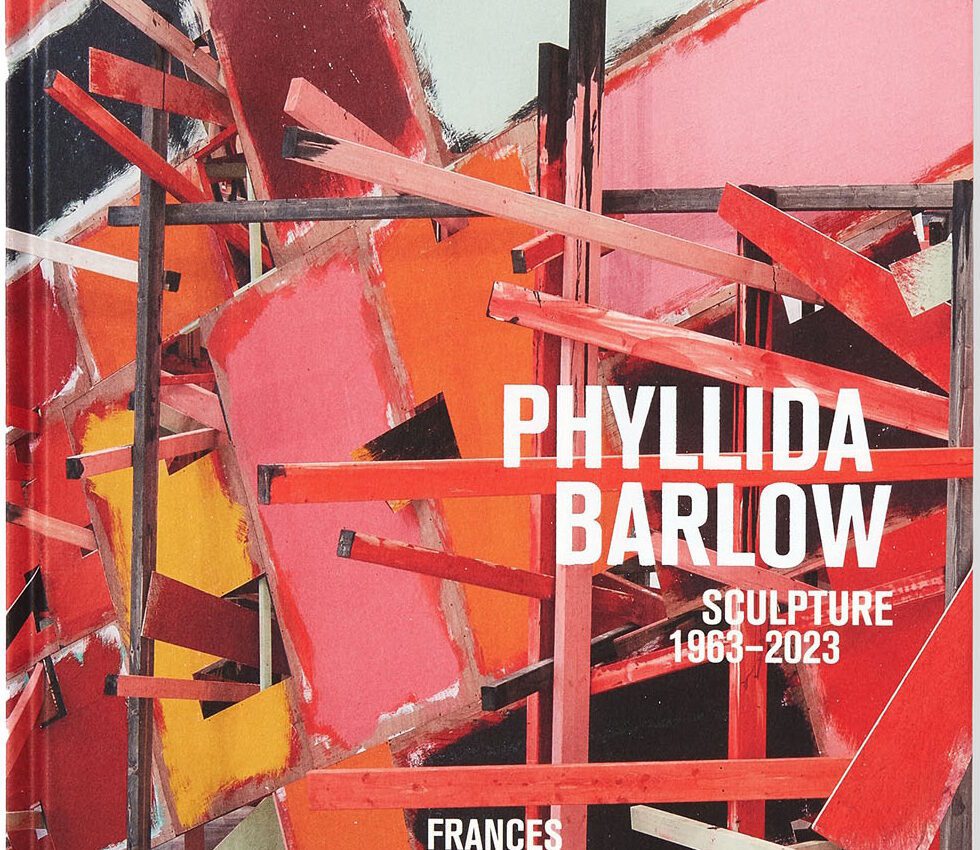

With Phyllida Barlow’s passing, the end chapters of her remarkable life are written in physical terms. Her influence, like the way her works inhabit spaces beyond the physical, continue to extend. Phyllida Barlow: Sculpture, 1963–2023 is a remarkable publication. Written with depth and detail, it shows Barlow’s work in the wider historical context of art from the ’60s to her death in 2024.

In accord with Camille Paglia’s 2017 declaration in Glittering Images that Warhol and pop art had rendered the academic overtures of the ‘Avant Garde’ dead, authors Frances Morris and Fiona Bradley highlight that Barlow’s work never fit completely within the lineage of academic art. Rather, it was always the product of a philosophical outsider. Beauty was secondary to the physical relationships that her works emphasised, but neither did Barlow eschew the aesthetics of beauty and awe. From the earliest, the sublime nature of her works elevates both materials and space by her use of structure. Bradley suggests her decades-long career traversed the naked space between orthodoxy and the revolutionary. Barlow was, after all, a renowned teacher for most of her career.

“[P]ost-structuralism… borrowed the old and outmoded linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure to postulate that everything that we know (or think we know) is mediated through language. This absurd claim — which can be instantly disproven by observing the daily lives of sculptors, painters, and dancers, all of whom are grounded in the material realm — became widespread in universities by the 1970s and has now poisoned the art world too” — Camille Paglia

She’s probably right. But the arrangement of materials in Barlow’s work feels like language when a contextual order emerges. Knotted canvasses, leaning painted planks, wedges protruding into space, iron towers of tables, all speak to us. The 2024 exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Somerset (25 May – 5 Jan 2025) ‘Phyllida Barlow, unscripted’ highlights not the absence of language but rather the a priori assumption that art is completed from the outset. By contrast, Barlow’s work is shaped through the process.

© Phyllida Barlow Estate. Courtesy Phyllida Barlow Estate and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fabian Peake

“The title ‘unscripted’ refers to the experimental and iterative nature of Barlow’s working process, allowing each project to evolve through a process of making, unmaking and remaking, involving chance and mishap as well as changes of mind. She saw this working practice as akin to processes of growth, decay and renewal in nature. Barlow was aware of the forthcoming exhibition and had begun to think seriously about bringing her interest in painting to the fore.” — Frances Morris, exhibition text.

Photo: Ken Adlard

The publication, which contains a wealth of large, high-quality pictures of Barlow’s work and acknowledges the limitations of presenting spatial art in a two-dimensional format. However, the book allows an overarching perspective as various aspects of Barlow’s work become recognisable and evolve over time. For instance, shapes like the ‘rabbit ears’ seen in Prank (2022-2023) have their roots in much earlier organic forms from the mid-’60s. In this respect, the book is invaluable for anyone interested in how Barlow’s work sits within contemporary installation and sculpture. The bittersweet reward is that there isn’t much now that doesn’t seem derivative of her and her contemporaries’ work. However, Morris’ insightful essays, based on her long association with the artist, give us inspirational accounts of how Barlow worked against the orthodoxies of her time. Lessons more relevant now than ever.

Phyllida Barlow: Sculpture, 1963–2023

Text by Frances Morris. Introduction by Fiona Bradley

Hardcover, 304 pages, £52 / $60 / €58

ISBN: 978-3-906915-93-7

Released 24 October 2024 (UK / EU), 1 February 2025 (US / ROW)

Phyllida Barlow, unscripted

Hauser & Wirth, Somerset

25 May 2024 – 4 Jan 2025

Durslade Farm, Dropping Lane, Bruton, Somerset BA10 0NL

Exhibition notes:

Curated by Frances Morris, ‘Phyllida Barlow. unscripted’ brings together a collection of the artist’s signature elements from several major installations, as well as a number of free-standing sculptures ranging from the early 1970s to work made in the last year of Barlow’s life. The landscape, courtyards and garden beyond the galleries are animated and disrupted by a selection of sculptures, including ‘PRANK’, a series of seven wonderfully—and deliberately—ungainly sculptures Barlow made for New York’s City Hall Park in 2023, shown for the first time in the UK.

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle