[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]H[/dropcap]oused in Claverton Manor on the outskirts of the Georgian city of Bath, the American Museum in Britain opened to the public in July 1961.

Gangsters and Gunslingers, which opens on March 23rd, brings together a series of artefacts evocative of a transition period in American history: the years of cowboys, gunfights, prohibition, racketeering, mobsters, snake-oil and the silver screen.

Curator Laura Beresford answers some of Trebuchet’s questions.

How did the American Museum start, and what sort of event or exhibition typifies it?

The intention behind the making of this (still unique) Museum was to foster historic ties between the US and the UK. The Museum was founded by John Judkyn (1913-1963), a British-born antiques dealer who had become a United States citizen in 1954, and Dr Dallas Pratt (1914-1994), an American psychiatrist and collector.

Both had seen terrible things during the Second World War. They believed that the only way to stop another conflict on this scale was to strengthen transatlantic ties by showcasing the traditional decorative arts of America in a European setting.

Inspired by historic house and ‘living history’ museums in the United States – notably Colonial Williamsburg (Virginia), the Shelburne Museum (Vermont), and the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum (Delaware) – Pratt and Judkyn adopted a similar style of presentation for their museum, with period room displays predominantly arranged in chronological order to showcase a particular design period.

In order to achieve this end, panelling and floors from demolished buildings in America were reconstructed within Claverton Manor. Acclaimed on both sides of the Atlantic, the American Museum’s collection consists of furniture from the late 17th to mid 19th centuries, Renaissance maps illustrating the New World, and folk art paintings, sculptures, and textiles.

Each year the Museum also produces temporary exhibitions that provide opportunities to explore areas outside our decorative arts remit. Many of these shows have a strong grounding in social history – such as Gangsters & Gunslingers – and thus provide an opportunity for us to investigate how past traditions still impact on present-day America.

There are some very interesting items collected together in the Gangsters & Gunslingers exhibition, where did the collector acquire them?

Many pieces were bought at auction but some of the really special objects were acquired directly from the families and friends of the ‘gangsters and gunslingers’ themselves. Mr Roberts acquired several items, for instance, from Clyde Barrow’s youngest sister, Marie. She told him that when Clyde came out of Eastman prison in the early 1930s (where he was repeatedly raped by a fellow inmate) he was a changed man – ‘as mean as a snake’.

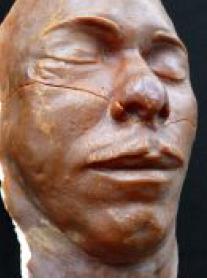

One almost imagines certain of the items to have a residual energy from their original owners. You have a death-mask which clearly shows the exit wound from the bullet that killed John Dillinger, you also have Clyde Barrow’s watch which was damaged by a bullet as he and Bonnie Parker were gunned down in 1934. Do any of the exhibited items resonate with you particularly?

When I handle Chief Gall’s war club, I am very aware that this is a sacred item.  The Hunkpapa Lakota leader was one of the commanders at the Battle of Little Big Horn (25 June 1876), which is also known as ‘Custer’s Last Stand’. It was largely thanks to Gall’s strategic planning that Custer’s forces were annihilated. Gall later claimed that surviving soldiers shot themselves rather than face their Sioux and Cheyenne adversaries in the final stages of the battle. That white men should show such cowardice was repudiated by the US authorities, who ruthlessly avenged this native victory.

The Hunkpapa Lakota leader was one of the commanders at the Battle of Little Big Horn (25 June 1876), which is also known as ‘Custer’s Last Stand’. It was largely thanks to Gall’s strategic planning that Custer’s forces were annihilated. Gall later claimed that surviving soldiers shot themselves rather than face their Sioux and Cheyenne adversaries in the final stages of the battle. That white men should show such cowardice was repudiated by the US authorities, who ruthlessly avenged this native victory.

As well as firearms, ceremonial weapons that won a warrior prestige by means of ‘counting coup’ were confiscated in retaliation for the Battle of Little Big Horn. Chief Gall’s war club was impounded after he surrendered to authorities in 1880. The officer who impounded this prestigious weapon scribbled details of Gall’s surrender on the club itself. He then presented the vandalised trophy as a ‘curiosity’ to a lady friend.

On a lighter note, I fell in love with Tyrone Power when I was seven so I am delighted to have his beautiful enamel cigarette case in the exhibition! Under the terms of his will, he left his body to medical charities for transplantation use. I wonder who later got to see the world through Tyrone’s beautiful dark eyes?

The exhibition is entitled Gangsters & Gunslingers. To what extent did the two provide depression-era America with a folk myth?

Like dime novelists in the late 19th century, journalists refashioned Depression-era outlaws for public consumption. These criminals were initially imagined as modern-day Robin Hoods; their exploits invested with noble intentions. In reality, these hoods robbed only for themselves and not for the benefit of the poor. Indeed, the poor were often their victims – robbed and murdered for a few dollars, gas, and groceries. By the mid 1930s, a new hero emerged in print and on film: the detective – defender of law and order.

The United States in the inter-war period seems to have been typified by the clean-cut ideal of the American dream. Prohibition, robust Christianity, the zealotry of Harry J. Anslinger. And yet the folk-heroes of the time were predominantly anti-establishment. To what extent does the exhibition reflect that urge for rebellion, and what do you think prompted it?

Money – or, rather, the lack of it – and a sense of entitlement. Gangsters weren’t the only ones to prosper in the Roaring Twenties. In 1929, America had 11,000 millionaires – twice as many as there had been at the start of the First World War. Fortunes were made overnight on the Stock Market, which was becoming increasingly unstable throughout  1929 as the sale of speculative shares soared. By late October, the accumulated debt of speculators being carried by brokers, who were in turn being financed by their banks, came to crisis point: on 29 October, over 16 million shares were offloaded and bankrupt investors began jumping from skyscrapers.

1929 as the sale of speculative shares soared. By late October, the accumulated debt of speculators being carried by brokers, who were in turn being financed by their banks, came to crisis point: on 29 October, over 16 million shares were offloaded and bankrupt investors began jumping from skyscrapers.

Industrial production crashed into recession as loan repayments were demanded. In the early years of the next decade, 3,000 banks failed throughout the United States and 15 million Americans were left unemployed. By 1933, a quarter of the labour force was jobless and many were hungry and homeless. Reflecting the social and economic changes of the time, a new type of anti-hero emerged in popular culture: the dispossessed outlaw, who was the victim of capitalism.

Sound familiar?

Is there a sense of loss, do you think, looking at these exhibits? Do they reflect a type of iconoclastic, individualistic American that can no longer exist?

Did he or she ever exist – apart from on film? A lone cowboy on his horse, surrounded by a sweeping landscape, remains a potent image of freedom and possibility – and not only for Americans. The gangsters financing movie-making were as inspired by this mythical embodiment of self-reliance as the Depression-era desperados. When it became their turn to be depicted on film, these modern-day outlaws were far removed from their non-celluloid selves.

The women represented in the exhibition are feisty individuals. Humphrey Bogart’s hard-living first wife Mayo Methot; Bonnie Parker, whose armed-robbery and killing spree across America with Clyde Barrow is now legend; Rita Hayworth, the screen starlet best known as a gangster’s wife in Gilda.  In an era of larger-than-life men, was it inevitable that the ‘broad’ is the enduring female archetype of the time?

In an era of larger-than-life men, was it inevitable that the ‘broad’ is the enduring female archetype of the time?

Not sure if I agree with this, although I concede that the femme fatale from noir film and fiction is a more seductive creature than the likes of Eleanor Roosevelt and the heroic migrant mothers photographed by Dorothea Lange.

With regard to Parker, she only really came to prominence after her death – most notably following the 1967 film starring the glamorous Faye Dunaway (who was nothing like Bonnie, apart from being blonde). During their lifetime, the criminal partnership ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ did not exist because Bonnie Parker was not considered a key member of their gang.

Clyde Barrow and his older brother, Buck, had the greater notoriety. Indeed, before Buck died in 1933, the group as a whole was known as ‘The Barrow Boys’ or ‘The Barrow Gang’ by the press and police.

The inclusion of mementoes from screen actors in the exhibition makes it easy to forget that much of what is exhibited are historical artefacts, once belonging to individuals who seem themselves more a product of the Hollywood imagination than genuine historical figures. You have a cigarette case which once belonged to Al Capone, Wyatt Earp’s gambling dice, a war club belonging to Chief Gall from the Battle of Little Big Horn, medical instruments used at the OK Corral. Events better known to most Europeans through movies rather than history books. Is it hard to separate the facts from the myths?

No-one did more to sell the popular myth of the West than Buffalo Bill Cody in his internationally renowned Wild West show. When Cody died in 1917, a new way of bringing the West to life had emerged. Los Angeles was the last Western boom town – a place where elderly cowboys mingled with celluloid stars on Hollywood backlots. Wyatt Earp ended his days there. Earp had no idea how great an American hero he would become after his death, when he was re-imagined by movie gunslingers such as Henry Fonda, Burt Lancaster, and Kevin Costner (to name but a few).

[quote]Los Angeles was the last Western boom town – a place where elderly cowboys mingled with celluloid stars on Hollywood backlots[/quote]

The survivor of the most famous of all the gunfights of the Old West was disgusted to find movie hucksters wary of the truth but only too willing to believe embellished tales of home-grown chivalry.  The great silent cowboy films stars William S. Hart and Tom Mix were among the pallbearers at Earp’s funeral in 1929.

The great silent cowboy films stars William S. Hart and Tom Mix were among the pallbearers at Earp’s funeral in 1929.

Historical truth has never stood in the way of a good story. In the classic movie western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), a character observes: ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’ There has never been a better way of summing up how the history of the Wild West and the wild years of the Prohibition/Depression era have been misrepresented.

If a similar exhibition were to take place in a century’s time, what artefacts do you think you would choose to illustrate America as it is now, and how do you think the narrative would differ from the frontier-freedom expressed in Gangsters & Gunslingers?

Oh come on – that’s an essay topic, not a question!

What’s my exhibition budget? It would have to be enormous because I would want to run amok with the NASA archive, especially with the new Mars explorations. To quote Star Trek: “Space… the Final Frontier… to boldly go where no [woman] has gone before.”

[button link=”http://www.americanmuseum.org/”] The American Museum in Britain[/button]

Images show:

The American Museum in Britain

Chief Gall’s War Club

John Dillinger’s Death Mask

Clyde Barrows’ Bulletproof Vest

Tyrone Powers’ Cigarette Case

Sidebar image: Carl Byron Batson

An observer first and foremost, Sean Keenan takes what he sees and forges words from the pictures. Media, critique, exuberant analysis and occasional remorse.