Generation Genocide: Punk doesn’t nurture it preserves!

The word ‘Punk’ must retire. Dispossessed from its ancient zeitgeist it bitterly refuses to die, refuses to compromise, and continues to eke out its existence in our parlance by being appropriated by bands and music it has nothing to do with. The musical evolution of ‘punk’ has seen two divergent species emerge; the sonically analogue and the spiritually analogous.

The ‘punk’ analogue stumbles out of every commercial guitar, every spiked hair style, and from every imitation of rebellion whereas the punk ethos remains at the fringe. So where does a night comprising of (at least) four generations of punk stand?

Gary Lammin: Punk Rock was an expression, a free expression, and if anyone tells me that you can’t do that, then that is already taking the template away from what punk rock music was supposed to be, and that is FREE expression.

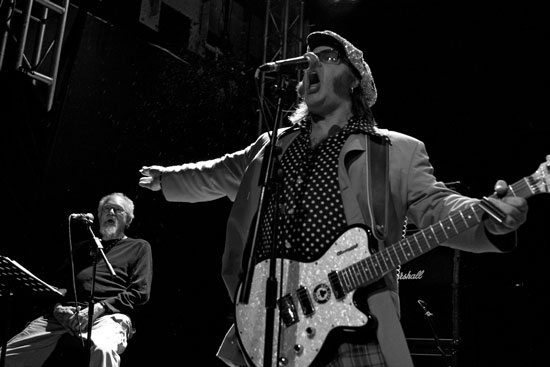

It’s hot. It’s cramped. It smells. It’s a backstage dressing room at the Islington o2 and I’m speaking to Gary Lammin of the Bermondsey Joyriders about his concept album Noise and Revolution. A song cycle recorded with the aid of the other man in the room, John Sinclair of the MC5.

Lammin: So when someone said to me ‘oh you’re going to make a punk rock concept album, that’s just not going to work’ I said to them ‘Oh yeah, fucking watch me’

I had the idea with me for many years. But I did something that was quite rare for me which was not act in an impetuous way and just go and do it because I had a great idea. Something was telling me that this idea was really good; don’t blow by doing it half baked. Just keep it because sometime in future the right people would come together.

I had the idea with me for many years. But I did something that was quite rare for me which was not act in an impetuous way and just go and do it because I had a great idea. Something was telling me that this idea was really good; don’t blow by doing it half baked. Just keep it because sometime in future the right people would come together.

I was on tour with the Bermondsey Joyriders a couple of years ago in the states and we were staying at a guy’s house in Long Beach, California who was a big MC5 fan.

You see, when we put the Bermondsey Joyriders together one thing that Martin Stacey and me agreed on that we would always keep in our minds the honesty and truth that MC5 were all about. There’s no way that anybody could replicate what they did but the honest and burning energy to express honesty was something that…

You see, when we put the Bermondsey Joyriders together one thing that Martin Stacey and me agreed on that we would always keep in our minds the honesty and truth that MC5 were all about. There’s no way that anybody could replicate what they did but the honest and burning energy to express honesty was something that…

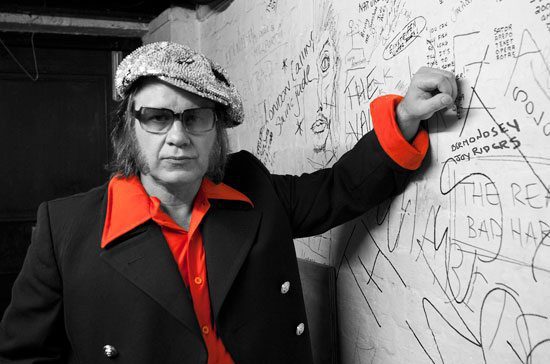

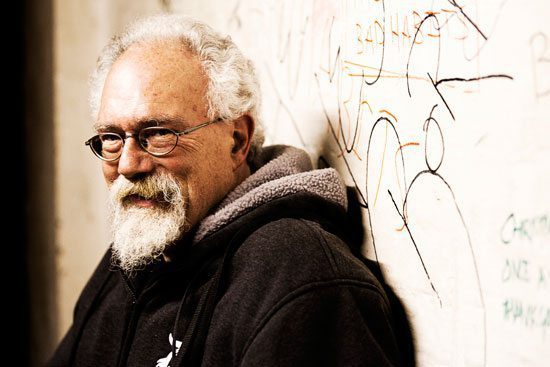

John Sinclair is man with a big history in music and in activism. Manager of the MC5, the proto punk rock band that set a benchmark for noise and expression, he was instrumental in focussing their antiauthoritarian feelings into a polarising and transparent ideology. Perhaps for the first time in pop music, message and rebellion came together as the definite package. Many artists had had affiliations and causes before then, but rarely, if ever, had a manifesto appeared on an album sleeve. A cynic would argue that this heralded the moment when political affiliation could be purchased for the price of a vinyl record, opening the door for the commercialisation of politics and pop, celebrity chat-show opinion and eventually Bono. A more optimistic reader might respond that a few bucks is a small price to pay for social change and if the revolution has to have a soundtrack it might as well be from artists that are in line with the cadre on the street. Released the same six months as ‘Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud’ by James Brown, ‘Kick out the Jams’ put it down that;

Brothers and sisters, the time has come for each and every one of you to decide whether you are gonna be the problem or whether you are gonna be the solution – The MC5

In 1969 John Sinclair was arrested for possession of Marijuana and sent down for a ten year stretch for dispensing two joints to a policeman. In the heyday of musical protest, celebrities came to his aid, including John Lennon and Stevie Wonder amongst other left-wing luminaries, culminating in his release two years later. Since then he’s continued to exert a popular influence; writing and performing poetry, doing radio shows, writing for pay, travelling and living in Amsterdam. He remains a free agent, but like punk, being free in Western society isn’t an easy road, and it eventually and inevitably exacts its toll. Sinclair is comfortable in himself, but you get a sense of weariness. The birthing process of creation is rarely glorious, it’s painful and leaves its marks. Many artists do their tours when young and leave the coalface, either to fatuous success or to other lives, few remain and there’s a cautionary nobility to those that do. Outside of the retrospective pages of musical histories, the reality of a life in music is damn real and it doesn’t nurture, it preserves.

In 1969 John Sinclair was arrested for possession of Marijuana and sent down for a ten year stretch for dispensing two joints to a policeman. In the heyday of musical protest, celebrities came to his aid, including John Lennon and Stevie Wonder amongst other left-wing luminaries, culminating in his release two years later. Since then he’s continued to exert a popular influence; writing and performing poetry, doing radio shows, writing for pay, travelling and living in Amsterdam. He remains a free agent, but like punk, being free in Western society isn’t an easy road, and it eventually and inevitably exacts its toll. Sinclair is comfortable in himself, but you get a sense of weariness. The birthing process of creation is rarely glorious, it’s painful and leaves its marks. Many artists do their tours when young and leave the coalface, either to fatuous success or to other lives, few remain and there’s a cautionary nobility to those that do. Outside of the retrospective pages of musical histories, the reality of a life in music is damn real and it doesn’t nurture, it preserves.

Sinclair listens to the energetic Lammin retell the story of the creation of the album. He smiles broadly and interjects with ‘yeahs’ and affirming chuckles. Sinclair’s eyes glow when Lammin discusses the honesty and energy of the MC5 with reverence adding;

Sinclair listens to the energetic Lammin retell the story of the creation of the album. He smiles broadly and interjects with ‘yeahs’ and affirming chuckles. Sinclair’s eyes glow when Lammin discusses the honesty and energy of the MC5 with reverence adding;

..don’t forget the love of music and humanity, both.

Lammin: So we’d done a 12 week tour and every night whenever we went on stage Martin and I would tell each other ‘remember the MC5’ and between times of gigging we were listening to the MC5, watching movies and DVDs.

I said to Martin Stacey we have to get in contact with John Sinclair. Martin being the level headed guy that he is said ‘We’re not going to get in contact with John Sinclair, he could be anywhere in the world’ and I thought ‘yeah you know, you’re right.’

So when we came back, and I put my hand on heart that this is the truth, a guy called John Brett that manages various underground scenarios, such as retro film posters etc had left a messages on my phone. You know you come back from a 12 week tour and there are a bunch of messages, and one of those messages was from John Brett: “Garry we like you to come down tonight and play some slide guitar behind John Sinclair’s poetry”

John: (Laughs): I didn’t even know this!

John: (Laughs): I didn’t even know this!

Gary: This is the truth John, on my life. So I phoned Martin up and I said; ‘Here, you know you said we’d never get in contact with John Sinclair’ and of course he was like ‘okay, hold on a bit I know these phone calls from you’ and that was a couple of years ago.

Now honestly, I was so enthralled by the being able to play with John Sinclair that it didn’t sink in. I walked around for a couple of months before I realised; that’s it, John Sinclair is, hopefully, the narrator for the concept album. But it took me six months for the bell to ring!

So I gave John a call, he was up for it and the album is called Noise and Revolution.

John: It’s a very simple story about a rock and roll band, that goes through various trials and tribulations…

John: It’s a very simple story about a rock and roll band, that goes through various trials and tribulations…

Gary: It’s about a band trying to get somewhere with the greatest intentions, doing it for a reason and then there’s pitfalls, as there always is, and then they blow it. But the redemption is in the fact that is something more important than being rock stars.

A punk rock concept album about a band that struggles for their own truth amongst their own egotistical ambitions comes across as the foundation of every album, punk or otherwise, ever recorded. But Noise and Revolution is a different beast, at once fun and raucous, there is a tautness and direction to its flow that draws the listener into its orbit. The narration by Sinclair counterpoints excellently with Lammin’s great lyrics and the band (Martin Stacey on bass and Rat Scabies on drums) play with a force and energy that is pure punk. Remarking to Lammin and Sinclair that there is still of a lot of blues in the sound Lammin leaves little doubt;

A punk rock concept album about a band that struggles for their own truth amongst their own egotistical ambitions comes across as the foundation of every album, punk or otherwise, ever recorded. But Noise and Revolution is a different beast, at once fun and raucous, there is a tautness and direction to its flow that draws the listener into its orbit. The narration by Sinclair counterpoints excellently with Lammin’s great lyrics and the band (Martin Stacey on bass and Rat Scabies on drums) play with a force and energy that is pure punk. Remarking to Lammin and Sinclair that there is still of a lot of blues in the sound Lammin leaves little doubt;

Lammin: Elmore James, Muddy Waters, it’s the reason why we started to play the fucking guitar!’

John: We’re bluesmen-

Gary: -It’s poetry. Blues is the poetry of rock and roll.

John: It’s the life stream of all music it’s where it came from and it still sounds and feels as good to me as it always has. I bought the first Chuck Berry record when it came out and I still listen to it right now, about ten times in a row.

John: It’s the life stream of all music it’s where it came from and it still sounds and feels as good to me as it always has. I bought the first Chuck Berry record when it came out and I still listen to it right now, about ten times in a row.

Alone with John Sinclair I circle around his continued role in music activism, where he’s been and what happened to the revolution. Silly questions really, too broad for an individual answer and feted for grandiose quotes coming straight from the inner geek, which if we’re honest may be the reason that many of you are reading this now. Sinclair’s patience seems to wear thin, he’s answered this one many times before. Was I rubbing it in?

John: It didn’t work. It’s crazy to keep to trying to do something that doesn’t work. So now I just do whatever I can get away with. I do my radio show.

I’m as well known as I’m going to be. The champagne fountains never turned on, all I ever got was water.

But I knew all this going in. I grew up in the beatnik era. That had the most appeal to me and that life never promised anything. Well they promised a whole lot, a lot of writing and being creative but poverty was assured.

But I knew all this going in. I grew up in the beatnik era. That had the most appeal to me and that life never promised anything. Well they promised a whole lot, a lot of writing and being creative but poverty was assured.

Sinclair seems to consider this at length. Sensing it’s a good time to change the subject I ask what his impressions of Lester Bangs were.

John roars: He wasn’t a journalist he wrote about himself foremost and he was an asshole. He killed the MC5 with that review he wrote in Rolling Stone. Things were good after that but that one review meant it never (expansive gesture) you know. After that things shut down a bit.

Bangs’ first Rolling Stone piece was a negative review of the MC5 album Kick Out The Jams (something he would later regret) which he sent to Rolling Stone with a note telling them that if they decided not to publish it they would have to contact him and tell him why. As it was they published it.

The Joyriders come into the room and start to get ready. Stacey, the wiry bassplayer, is very calm as Lammin checks and rechecks everything, tunes his guitars, and handles the seemingly endless minutae of the gig. There are calls from people requesting tickets and attention, all of whom Lammin answers, upbeat and friendly, despite pre-gig nerves.

The Joyriders come into the room and start to get ready. Stacey, the wiry bassplayer, is very calm as Lammin checks and rechecks everything, tunes his guitars, and handles the seemingly endless minutae of the gig. There are calls from people requesting tickets and attention, all of whom Lammin answers, upbeat and friendly, despite pre-gig nerves.

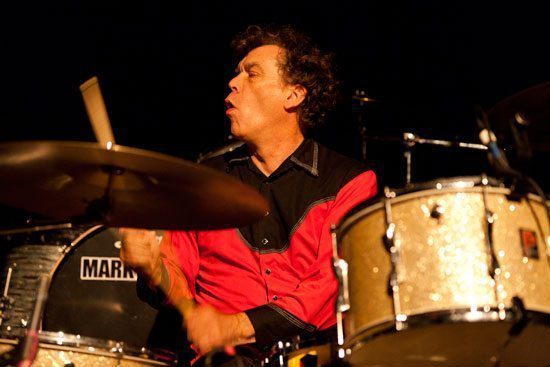

Rat Scabies (The Damned) their regular drummer has been called away to do some film work, his replacement Eddie from The Vibrators looks preoccupied and wanders in and out of the dressing room. It’s not a small gig. They are supporting what remains of the Ramones. Many people will not have heard of them. National press are present. It’s an evening of first impressions. Each man is aware that tonight they have to deliver big and all conversation ceases.

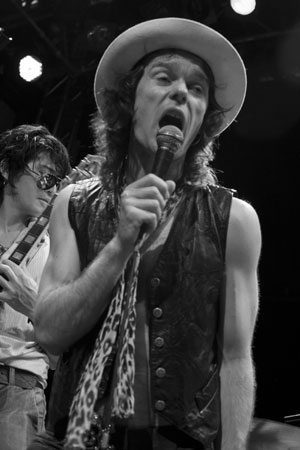

The crowd has barely started to filter in by the time Bubblegum Screw go onstage, they’re dirty, sleazy looking and ready to get busy with whoever is in front of them. The lead singer makes the most of his passing resemblance to David Johansen of The New York Dolls which is backed up musically by the rest of the band.

The crowd has barely started to filter in by the time Bubblegum Screw go onstage, they’re dirty, sleazy looking and ready to get busy with whoever is in front of them. The lead singer makes the most of his passing resemblance to David Johansen of The New York Dolls which is backed up musically by the rest of the band.

It’s a tough slot; people are sober and it’s still early but the band manage to get the crowd out of first gear and into party mode. Something of a London institution, the roll call of musicians that have played in The Screw runs into double figures, despite this the central offering has remained the same throughout; broad spectrum rock and roll, played with speed and snarl. The lead singer cranks out the lyrics with passion and vitriol. It’s classic stuff and reminiscent of a lot of precedents, the songs are tight and the look is spot on, but the night ain’t right. There’s little sweat in the crowd, people nod casually, toes tap, but this is a ride that has to be appreciated in a small packed club of abandon not on an early evening stage that belongs to someone else. They’re worth witnessing but the gig missed the testifying experience you expect from The Screw.

It’s a tough slot; people are sober and it’s still early but the band manage to get the crowd out of first gear and into party mode. Something of a London institution, the roll call of musicians that have played in The Screw runs into double figures, despite this the central offering has remained the same throughout; broad spectrum rock and roll, played with speed and snarl. The lead singer cranks out the lyrics with passion and vitriol. It’s classic stuff and reminiscent of a lot of precedents, the songs are tight and the look is spot on, but the night ain’t right. There’s little sweat in the crowd, people nod casually, toes tap, but this is a ride that has to be appreciated in a small packed club of abandon not on an early evening stage that belongs to someone else. They’re worth witnessing but the gig missed the testifying experience you expect from The Screw.

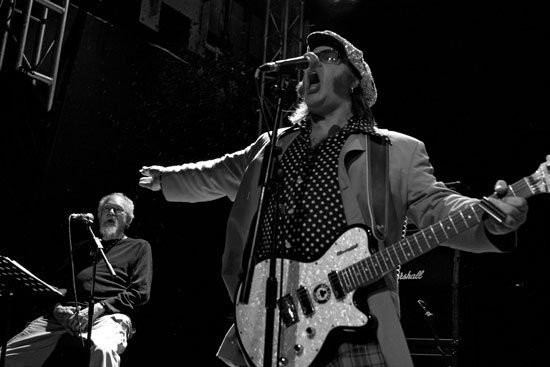

Entering the stage with glam-punk flair the Bermondsey Joyriders are a splash of tartan and attitude. The dressing room doubt has been replaced with a thin-lipped purpose. Sinclair takes up his position at the side of the stage. There is a beat as they look at each other and then a collective scream of noise. Lammin’s guitar slashes out a wall of distortion, cymbals crash, and a volcanic rumble pulses through every ear. The band have taken the stage, this might be Marky Ramone’s night but this hour belongs to the Joyriders. As the noise builds to a crescendo Lammin and Stacey smash their instruments, Eddie’s possessed toms pound hard and crashes explode. So begins Noise and Revolution.

Entering the stage with glam-punk flair the Bermondsey Joyriders are a splash of tartan and attitude. The dressing room doubt has been replaced with a thin-lipped purpose. Sinclair takes up his position at the side of the stage. There is a beat as they look at each other and then a collective scream of noise. Lammin’s guitar slashes out a wall of distortion, cymbals crash, and a volcanic rumble pulses through every ear. The band have taken the stage, this might be Marky Ramone’s night but this hour belongs to the Joyriders. As the noise builds to a crescendo Lammin and Stacey smash their instruments, Eddie’s possessed toms pound hard and crashes explode. So begins Noise and Revolution.

As the distortion and feedback dies away the set begins, amongst the anthemic punk songs Sinclair narrates the ongoing vicissitudes of the band. The punk rock anthems hit the Screw warmed crowd and the revolution starts to roll. The stage is a strange place, the older guys I spoke to in the dressing room are all transformed, virile and volatile, the unlined and slim young punkettes spin and shout, looking up at people whose individual musical history has more years than their parent’s lives. With each song punters swell the ranks, dancing along, clapping and finally cheering.

As the distortion and feedback dies away the set begins, amongst the anthemic punk songs Sinclair narrates the ongoing vicissitudes of the band. The punk rock anthems hit the Screw warmed crowd and the revolution starts to roll. The stage is a strange place, the older guys I spoke to in the dressing room are all transformed, virile and volatile, the unlined and slim young punkettes spin and shout, looking up at people whose individual musical history has more years than their parent’s lives. With each song punters swell the ranks, dancing along, clapping and finally cheering.

Sinclair looks over to me at the side of the stage; the weariness is gone, the water tastes like wine, he gives me the thumbs up and nods knowingly. Narrating deep in the language and the fire of the 60s beat protest movement, old forms and cadences are tense, relevant, and capture the young crowd.

Sinclair looks over to me at the side of the stage; the weariness is gone, the water tastes like wine, he gives me the thumbs up and nods knowingly. Narrating deep in the language and the fire of the 60s beat protest movement, old forms and cadences are tense, relevant, and capture the young crowd.

Lammin’s gamble on the concept album has hit home, the concise, fatless song writing has paid off. Sinclair’s voice lifts into Lammin’s lyrics, echoing sparse Carver or Bukowski-esque descriptions of a social punkscape. Charting the death of a dream and a better life in the waking dirt of existence this is undoubtedly Lammin’s reflection on his own history. Wouldn’t it be more honest to openly autobiographical? Perhaps, but consider the idea that sometimes there are more available truths in stories of conviction than there are in personal histories. The Bermondsey Joyriders have a lot of conviction, they have a lot of truth.

Lammin’s gamble on the concept album has hit home, the concise, fatless song writing has paid off. Sinclair’s voice lifts into Lammin’s lyrics, echoing sparse Carver or Bukowski-esque descriptions of a social punkscape. Charting the death of a dream and a better life in the waking dirt of existence this is undoubtedly Lammin’s reflection on his own history. Wouldn’t it be more honest to openly autobiographical? Perhaps, but consider the idea that sometimes there are more available truths in stories of conviction than there are in personal histories. The Bermondsey Joyriders have a lot of conviction, they have a lot of truth.

Can I see your identity please Mister?

Noise and Revolution contains the Joyriders’ constant struggle against personal limitations, history, and internal and external suffering. Teenage angst? Hell yes, Punk refuses middle-aged resignation with youthful optimism. Lammin and John are forthright in their use sound as energy, of honesty, of dirty primalism at the pedestal of civilised oppression. This is the uncivilised seed of revolution, rooted in the desire for change. Punk, it seems flowers in decay. It contains a bitter poetry; potent, poignant and poisoned, a message that isn’t limited by generation but by position and intent. Punk never really appeals to the haves, it remains the realm of the dispossessed, and never to the advantage of those whose lives are spent preaching ‘revolution’ to those most affected. A downer for sure, but it certainly beats learning ‘Walking on Sunshine’ for the wedding circuit of the dayjob musician.

Noise and Revolution contains the Joyriders’ constant struggle against personal limitations, history, and internal and external suffering. Teenage angst? Hell yes, Punk refuses middle-aged resignation with youthful optimism. Lammin and John are forthright in their use sound as energy, of honesty, of dirty primalism at the pedestal of civilised oppression. This is the uncivilised seed of revolution, rooted in the desire for change. Punk, it seems flowers in decay. It contains a bitter poetry; potent, poignant and poisoned, a message that isn’t limited by generation but by position and intent. Punk never really appeals to the haves, it remains the realm of the dispossessed, and never to the advantage of those whose lives are spent preaching ‘revolution’ to those most affected. A downer for sure, but it certainly beats learning ‘Walking on Sunshine’ for the wedding circuit of the dayjob musician.

With a wave and a bow the Bermondsey Joyriders leave the stage to applause, visibly mixed with emotions of relief and elation. Back in the dressing room Lammin sinks into the battered sofa, closes his eyes for a second, and pulls out a piece of paper. Within seconds he’s back on the phone, dealing with the venue, making sure Sinclair is taken care of and organising the packing and stowing of equipment. For Lammin, tonight’s gig will probably end in the small hours of the morning but is made that much easier by the knowledge that the performance part of the gig went well. I drift out to see the final and headline act of the evening Marky Ramone.

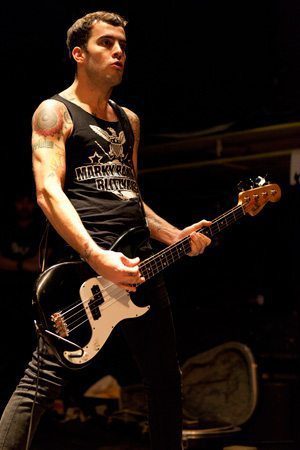

Marky Ramone’s Blitzkrieg makes a claim to the Ramones legacy and feeling the crush of bodies as they blast into Rockaway Beach they are obviously catering to a clear audience need. Along with Marky the band includes Michael Graves from post-Danzig Misfits and a couple of guys steeped enough in punk lore to kick it out of the park.

Marky Ramone’s Blitzkrieg makes a claim to the Ramones legacy and feeling the crush of bodies as they blast into Rockaway Beach they are obviously catering to a clear audience need. Along with Marky the band includes Michael Graves from post-Danzig Misfits and a couple of guys steeped enough in punk lore to kick it out of the park.

While controversial it has to be said that Blitzkrieg have more energy than the Ramones had in the 90s and play through a classics set (and weren’t all Ramones sets that way) with fierce attention to the original fire. Are the audience considering what they missed more than what’s before them? It doesn’t seem so. The audience is alive, every voice singing, word perfect, to lyrics that in some cases are tattooed on their bodies. This is a proper punk show and not an imitation. The young accompanists make the songs their own, spitting teeth while Marky pours petrol on the skins. The set is relentless and has everyone jumping from start to finish. It’s fair to say that for a lot of younger fans the experience borders on religious, such is the place the Ramones have in their hearts and filtering into the night it’s clear that on the edges of social relevance punk remains central to many people’s lives.

While controversial it has to be said that Blitzkrieg have more energy than the Ramones had in the 90s and play through a classics set (and weren’t all Ramones sets that way) with fierce attention to the original fire. Are the audience considering what they missed more than what’s before them? It doesn’t seem so. The audience is alive, every voice singing, word perfect, to lyrics that in some cases are tattooed on their bodies. This is a proper punk show and not an imitation. The young accompanists make the songs their own, spitting teeth while Marky pours petrol on the skins. The set is relentless and has everyone jumping from start to finish. It’s fair to say that for a lot of younger fans the experience borders on religious, such is the place the Ramones have in their hearts and filtering into the night it’s clear that on the edges of social relevance punk remains central to many people’s lives.

Four raging generations of punks in single night; the 60s, 70s, 80, and 90s clamouring together against the odds, obscure and hardly thriving; from Sinclair, to Marky, to Lammin, even to the Screw, they have all managed to remain. If only because their message, their ethos of never giving up, of reflecting a street level honesty, appeals to people who can’t or refuse to have access to the mainstream stance of welcoming the sale of the self as a means to an end.

Four raging generations of punks in single night; the 60s, 70s, 80, and 90s clamouring together against the odds, obscure and hardly thriving; from Sinclair, to Marky, to Lammin, even to the Screw, they have all managed to remain. If only because their message, their ethos of never giving up, of reflecting a street level honesty, appeals to people who can’t or refuse to have access to the mainstream stance of welcoming the sale of the self as a means to an end.

The honest truth is that they all want to reach as many people as possible, they want to affect as many people’s lives as pop stars, but they can’t. Not because they don’t try as hard, and not because they aren’t as talented, but because punk has never preached escapism.

The honest truth is that they all want to reach as many people as possible, they want to affect as many people’s lives as pop stars, but they can’t. Not because they don’t try as hard, and not because they aren’t as talented, but because punk has never preached escapism.

Artists like Bubblegum Screw, The Bermondsey Joyriders and the Ramones are unable to present illusion, are unable to sell unattainable dreams, because they are unambiguously truthful people. Not necessarily because they are high minded nice people, though they are, but because they can only be as they appear, take it or leave it. Revolution can only come about by a group of unashamed people who refuse to accept the idea that poverty, powerlessness, and humiliation are inevitable outcomes to a hard worked life. The problem is that we live in an ashamed society, that on the one hand convinces us that we’ve lied to get ahead, and on the other, that because we’ve lied we aren’t deserving. The idea being, that if you think you’ve got away with something you’ll never speak up. What Punk declares is that there is a true core to your being that isn’t false, and that unfettered by pop dreams it deserves better. Self respect is the action, self worth is the outcome, and honesty is the virtue. Long live punk rock and roll.

Artists like Bubblegum Screw, The Bermondsey Joyriders and the Ramones are unable to present illusion, are unable to sell unattainable dreams, because they are unambiguously truthful people. Not necessarily because they are high minded nice people, though they are, but because they can only be as they appear, take it or leave it. Revolution can only come about by a group of unashamed people who refuse to accept the idea that poverty, powerlessness, and humiliation are inevitable outcomes to a hard worked life. The problem is that we live in an ashamed society, that on the one hand convinces us that we’ve lied to get ahead, and on the other, that because we’ve lied we aren’t deserving. The idea being, that if you think you’ve got away with something you’ll never speak up. What Punk declares is that there is a true core to your being that isn’t false, and that unfettered by pop dreams it deserves better. Self respect is the action, self worth is the outcome, and honesty is the virtue. Long live punk rock and roll.

Marky Ramones Blitzkrieg/Bermondsey Joyriders/Bubblegum Screw – London, Islington 02 Academy – 26th June 2011

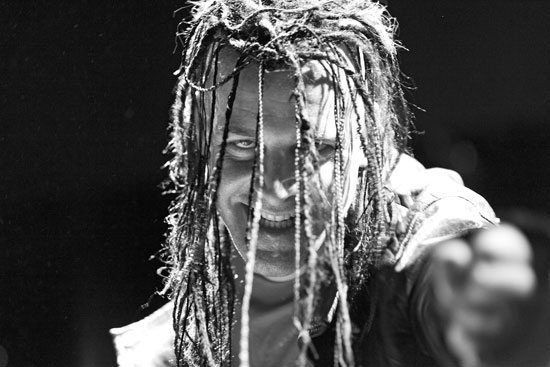

Photos: Carl Byron Batson

Trebuchet editor and art critic. Kailas is often away in some distant city searching for the latest artistic vision of the future. He has written for Trebuchet for over a decade, specialising in art theory as it evolves in contemporary art, the re-emergence of the monumental, and the personalisation of Modernist tropes in individual works.