“To physically taste war is completely different than to experience it second-hand.

The first lesson taught by physically tasting war is that ruination is the essence of all being. Death has no meaning and everything can be reduced to nothing in seconds.”

Housed in the North Lodge of University College London is a small, ten-day exhibit of artistic responses to the War in Iraq curated the university’s Dr. Alan Ingram. Based on research conducted by the Ingram and the UCL Department of Geography, the exhibition spotlights six pieces of artwork which together form a probing commentary on — put summarily — the war’s disorientating effect on notions of space and territory.

Geographies of War – The Iraq War Revisited.

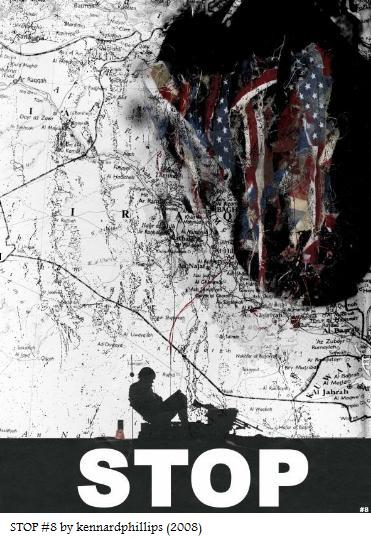

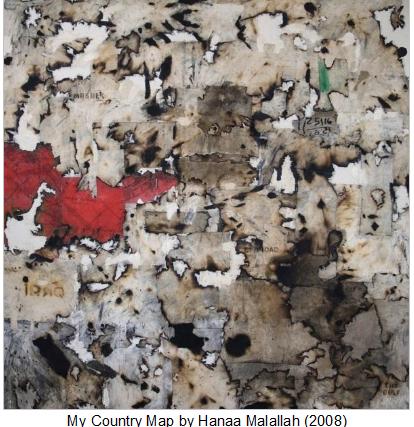

These six works are all, in varying ways, formed upon ideas of landscape. Though adorning just four walls in a small white room off Gower Street, there is an immediate sense of spatial depth as you enter, and are faced with the assaulted newsprint mapwork of Peter Kennard and Cat Phillipps’ ‘STOP#8’, and just adjacent to it, Hanaa Malallah’s ‘My Country Map’: a square of multi-layered burnt canvas work evoking a map of the Middle East.

The effect is appropriate, as the sense of ‘depth’, of expansive worlds behind these walls transforms an otherwise spare, confined space. The detail and texture demands study, and there is an immersive and almost hypnotic quality to Malallah’s in particular, a quality it shares with the newest and I daresay, most visually arresting of the pieces on display: Yousif Naser’s ‘Black Rain’ (created in 2012 and owing a clear debt to the expressionists).

The other three works are Emily Johns’ ‘Victory Palms’ (2008), a postcard which draws on English wartime traditions; ‘Buhriz’ (2004) by Satta Hashem, an intricate ink drawing of Buhriz during the American siege, which nimbly captures the bedlam of war-torn streets in overlapping images from Mesopotamian myths and the city itself; and ‘The Enemy Within: Driving in Iraq’ (2009) by former soldier Douglas Farthing, a heavily-annotated study of an Iraqi street as seen from the front window of his army land rover.

I want to, but simply won’t, restrain from launching into all manner of personal interpretations. I have almost no connection to Iraq (although my dad and aunt actually lived there as children) and whatever the locality the subject —war, that is— is a difficult one to broach, or at least to do so without being extremely boring and respectful. These artists all do a fine job, and the works are truly mesmerising, if you can approach them as seriously as they take their matter. Yes, it is all very arch and solemn.

These six creations all have very different relationships with spaces they describe; they make different negotiations with it. Some are obtuse, some automatically challenging, some portentous, some less so. Some are knowingly contemplative and quite obviously thoughtful, while others seem to me (based on intuition alone) works of pure and remarkable instinct. Only one—well, two, if you’re being generous—would appear to have a slight sense of humour, by which the whole set is much improved.

[quote]works of pure and remarkable instinct[/quote]

The skill in Dr. Alan Ingram’s curation has been to cultivate room for all manner of interpretations which these artists in isolation might never have intended, much less desired, while bringing quite starkly to light a fascinating set of variances and resonances.

Ingram’s choices clearly betray a developed thesis on artistic conceptions of space. Their interrelation, for what it’s worth, showcases the rather striking emergence of an art mode for which negotiations of space become the primary tool for discussing disjointed exterior and interior realities.

Said with warmth, British duo Kennard and Phillips’ (kennardphillips’) piece from their acclaimed STOP series is intentionally and brazenly critical of the war, and depicts American occupation as a kind of catastrophic violence wreaked upon the Middle East, a burnt hole in an atlas, a scar on the face of the Earth. It stops short of propaganda and elevates its message with the image of the burnt stars and stripes, offensive to many Americans, which for my money contains an overt suggestion that the foreground’s relaxing soldier in silhouette is quite unaware of the mutual destruction the war has wrought upon American dignity and Iraq, whose borders and territories are deformed and decayed by the fray.

The grouping of burnt map and burnt flag as comparable totems resonates with the deeply personal work by Malallah. The occupation, as in the British duo’s work, has been rendered a campaign of utter infernal destructiveness. Malallah’s patchwork of tattered canvas struck me as an act of reassembly, an ordering of chaos, befitting her position as an academic in exile. Its jagged contours, particularly those of its bottom-right corner, seems particularly evocative of the arbitrary brutalities which compose our political borders.

Cartography becomes a representation of history and its atrocities, and yet adding to the annals of history can itself be an act of violence perpetrated against that history. An odd bit of Arabic text, upside down along the top, juxtaposed with the chunky English writing elsewhere suggests that disorientation lingers on in the aftermath of chaos. Malallah depicts vertigo on the precipice of oblivion. She describes ‘My Country Map’ as an exploration of space “between figuration and abstraction, between existing and vanishing.”

In the case of both works, obsession with cartography opens up a space to discuss consequence as opposed to simple happening.

Directly opposite Malallah’s map, ‘Black Rain’ seems a paradox; its “black rain” is rising smoke, its falling rain white, descending sparks. To the left of its central image of a featureless woman is ruinous, hollowed-out Iraq; to the right, a sprawling London high-rise under a decadent disco ball moon. This juxtaposition creates a haunted figure in the middle, and the surprising depth and detail of its buildings when studied up close evokes a frail, quivering midnight from which other images are faintly distinguishable: the heads of Cerberus, seemingly, among them.

Stunning flares of white and creeping, transfiguring miasma against its featureless but evanescent female figure would suggest, as in other pieces, some deep connection between the violence and reassembly of the external world and an equally tumultuous dissolution of the self. For these artists, representation of territory and space in disarray acts as a potent mirror to psychic horror as well.

[quote]the violence and reassembly of the external world and an equally tumultuous dissolution of the self[/quote]

Naser’s shaking, battered city is quite different from the simple horror in clean lines seen in Johns’ ‘Victory Palms’, where broken palm trees are littered like tombstones and a solemn Iraqi woman looks to them and the moon overhead, contemplating the intertwinedness of victory with defeat let’s say, and seeing in her landscape smashed symbols of an assaulted culture. Its cleanness suggests wry humour of a very black kind, its style both a mediation and a subversion of tradition.

Johns’ piece, in form, seems the most engaged with the idea of transmission, and altered landscape is not simply its subject but a critical component of its fundamental question: a postcard to whom? A letter of reply, let’s assume.

Hers is the only piece in which the outward reverberation of chaos, or the difficulties of demarcation, is not an apparent theme; it is instead, in its composition, a tribute to composure. Of all the female Iraqi figures shown in these works, hers is the stoic onlooker, while the others are cast in the role of helpless victim. Like the others, she has neither face nor name, but she at least, most poignantly, has a kind of serenity. Hers is the only woman placed into the role of watchful artist, the same role the soldier assumes in Farthing’s piece.

Farthing very emphatically draws a boundary between a mental space which has no immediate sense of neither order nor physicality, and the physiospatial view of a woman on a deserted track, a street unwinding into the horizon. His clear demarcation between mental and physical is the only unsullied or unscathed ‘boundary’ in the exhibit. In the experience shared in his painting, there can be no unity between thought and sensory experience. The elision itself becomes subject to scrutiny. “Culpability = Intent,” “Iranian influence,” “We are on their patch,” “Kidnap,” “Beheading,” “Too Many Friends,” but a few of these stray thoughts read.

[quote]the littered crater of utter bombardment[/quote]

It is impossible to escape the theme of violence, and its resonances with the literature of colonisation are striking—where divided geographies stand in for divided cultures, divided identities, torn traditions. Here the wound is not the faultline of two races, but the littered crater of utter bombardment, shock and awe, scarring and dismemberment

“To physically taste war,” reads a quotation from Malallah in the brochure, “is completely different than to experience it second-hand.” This exhibit divides up neatly into second-hand evangelists and first-hand taste-testers and the question of authenticity rears its head.

The degree of congruence between these works bears testament to an adroit arrangement, but either picks too shallowly from the available responses to the war or indicates rather limited responses of artists this decade past.

One difficulty with enjoying the exhibit is acknowledging and moving on from the knowledge that several of these pieces are best understood in their original series, and may contain unavailable meanings. The works are themselves disoriented, transplanted, in alien space.

Shades of more interesting emotions than horror and awe crop up sparingly — somewhere in the nettle of overlapping lines, I was at least able to fleetingly glimpse the negotiation of guilt, its limitations and propriety — but overwhelmingly, amidst transfigurations of personal and impersonal, something is ultimately lost to the overwhelming force of the political difficulties faced in discussing war.

Perhaps the missing component is American culture and its more pronounced schisms and conflicts, some controversial dissent from the accustomed images of war, be that in the form of guilt-ridden neocon soul-searching, or unapologetic gusto from the school of Hitchens. But perhaps I am wishing for what does not exist.

For all its initial explosion of space, and for all the immersion these six works provide, after twenty minutes or so the walls of North Lodge begin closing in again. At no fault of the curator or of the talented artists whose works are on display, finity and limitedness becomes all too apparent.

You remember what art is. A medium for questions. A starting point. A catalysing agent in the prevailing culture. At this point, reality intervenes.

Space runs out, the maps reach their end. The world begins to turn the right way up.

And where are you?

Geographies of War – Iraq Revisited is at The North Lodge at UCL, 18-27 March 2013

Geographies of War is part of the Reel Iraq Festival organised by www.reelfestivals.org which takes place across 9 UK cities and promises an enlightening display of contemporary Iraqi culture featuring live music, film screenings, poetry readings, art exhibitions, panel discussions and music workshops

[button link=”http://www.ucl.ac.uk/iraq-war-geographies”] Geographies of War Homepage[/button]

still a very proscribed and two-dimentional idea of what ‘space’ is. simplicity can be a good thing, but not when it is simplistic. kennard in particular was much better when he was pushing the boundaries of the image and its use in space. this collaboration is simply meh. and the curation is a little fawning.