[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]’G[/dropcap]ive a man a mask and he’ll tell you the truth’

The Pennsylvanian born artist George Catlin (1796-1872) made five trips to the Western United States documenting the way of life of the indigenous tribes, still relatively untouched by European culture. Claiming an opposition to white encroachment on Native lands he produced a remarkably extensive collection of portraits and writings in an attempt to preserve a ‘vanishing race’.

Catlin is, however, usually remembered as something of a showman. Indeed, the last time paintings from his touring ‘Indian Gallery’ were in England, it was only when they were accompanied by an all dancing troupe of native Ojibwas that they began to rouse any real attention.

[quote]an affecting impression

of a man and the

affinity which he

found with his

subjects, though always

remaining on the

outside[/quote]

Fifty of those portraits have now returned to England following part of the path of the original collection between London and Birmingham.

In an interview for The Guardian upon the publication of his book Consolations of the Forest-A Record of Going Nowhere Sylvian Tesson suggests that his notebook, filled with the tangible evidence of memory – postcard, dried leaves, ticket stubs, slivers of whale skin – is his place of refuge:

“In the absence of anything else, it is my home . . . the anchor I let down.”1

The records that we make of ourselves, experiencing the world at different moments, become a point of reference for our identity. Likewise, one feels upon entering the gallery that Catlin’s amassed portraits and writing read as much as a frantic and obsessive exercise in personal archiving, as a testimony to true artistry.

The embellished gushings of Catlin’s poetic descriptions of the Indian tribes in which ‘the history of battles on a robe would fill a book if properly translated’, his boasts of ‘exciting fury’ in a buffalo to achieve the scene he required to paint and, attempts at self publicity that amounted to a series of vulgar freak shows, may easily be construed as self indulgent dross.

However, when placed quietly alongside the paintings in the dimly lit grandeur of the Birmingham museum they adopt a sense of poignancy. This is not merely a portrait of a lost civilisation. Behind each pair of eyes we see the gaze of a man scrabbling at the seams of another culture in order to prove his worth as both individual and artist.

It is this that perhaps elicits the incongruity between the gravitas associated with a salon hang and, the caricaturist quality of many of the paintings in the selection from the Indian Gallery. The battle to create a tradition for a disappearing culture could equally be a struggle to carve a reputation that will outlive him. A collector’s drive: to annihilate time with the amassing of objects; in the hope of preserving an associated memory – is evident in the urgency of his output.

Hence, the sense of loss that pervades the show can be seen to emanate, not only from the political context of colonialism but, from the conflict between the manner in which Catlin wished to be remembered. Striving to achieve mastery as a painter, archivist, showman and anthropologist, in the end none of these areas, cohesively or individually, shine out. He may have shaped much of our impressions of Western First Nation culture, however, this does not appear to stem from particular skill or factual precision (his theory of the gulf stream exhibited here is accompanied by the description: ‘proven scientifically incorrect’).

It is rather the fact that, in many cases, his is the only record we have. This is a point he appears to have realised himself as he trespassed on the sacred ‘Pipestone Quarry’ to capture the painterly equivalent of an ‘instagram moment’. One thing that has at least outlived him is the naming of the stone from the quarry after him.

Catlin is victim to the universal condition that, however much we try to project an image to the future of how we wish our present to be remembered, we are always subject to the editing of retrospect and, to our own strengths and limitations. There is never an objective ‘whole’ within history, at least where our aspirations are concerned.

The Western American Indian subjects gaze defiantly out of their frames, seemingly unaware of their impending total eclipse in the new dawn of mass colonialism.

There is a prophetic element in Catlin’s documentary technique to the photographs of Humphrey Spender as part of ‘The Mass Observation Project’ of the 1930s which is to be exhibited at The Photographers Gallery. The aim of the latter project was to:

‘study the ordinary lives of ordinary people in order to counteract the stereotypes that held sway in the British media of the time.’2

The photographs were only ever intended as pure information and as a supplement to the writing which, formed the core of the project. In spite of this Spender’s tendency to allow the camera to wander around his primary subjects has led to his acclaim as a ‘poet-photographer’. This is a matter of retrospective aesthetic contextualization however since, in addition to the pooling of individual skills on the part of the founders, many of the interviews were conducted by amateur volunteers. Aspirations to individual fame were certainly not on the original agenda.

In Catlin’s case we can observe how his style developed from the inspiration of the Indian facepaint and strong bone structure. He absorbed their culture and subsequently performed his sense of a unique style in his paintings. The extent to which this succeeded, both artistically and in terms of documentary prowess, is exposed in his landscapes which are distinctly flat and drab compared to the portraits. Face paint may work for face paint but not for mountains. Herein perhaps lies another reason, in addition to his preference for human subjects, as to why these canvases are few and far between.

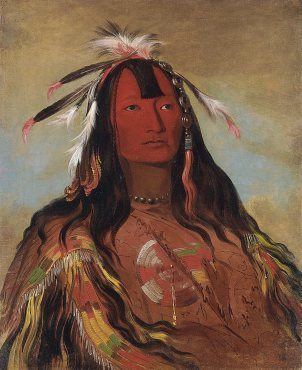

Indeed, with regards to the portraits themselves, the tribal adornments and ceremonial costumes are certainly impressive, however, there is also a sense that they are imitating their own authenticity. The image of ‘Little`Whale’ (1838) in particular, exudes a dandyish quality of affectation, despite the clothes being his own and his status being of a warrior.

One can’t help but be reminded of the paintings of daily life of First Nation tribes which he created on his return to London. In these works Catlin pandered to public demand to see the lives of a seemingly mystical people re-enacted. To produce them he elaborated wildly on what had been mere sketches in notebooks.

Glancing over at the slightly disproportionate , squashed figures inhabiting the frames from the Indian gallery, it would seem that his whole life in a sense was a caricature of himself, striving to be accepted. His fate is not simply aligned to but, could in fact be, that of his subjects.

Catlin’s dream had been to sell the collection to American congress so that his life’s work would be preserved intact, yet his incessant petitioning failed. In 1952, the original Indian Gallery, now 607 paintings, was sold due to personal debts.

He spent the last 20 years of his life trying to re-create his life’s work. These pieces were referred to as the ‘Cartoon Collection’ since they were based on the outlines of those from the 1830s. The irony cannot really be overlooked.

It is not, however, a sense of an inflated ego that one carries away. Rather it is an affecting impression of a man and the affinity which he found with his subjects, though always remaining on the outside. Most notably the portrait of a ‘Pretty Girl’ betrays an enchantment on the part of a painter whose paintbrush accentuates and fixates upon the ‘bright silvery grey of her hair’. Catlin is at his best when he captures this moment of alignment with the sitter.

In amongst the dead surfaces and rushed brushstrokes there are moments of true dignity. These moments come, not so much from the finery of the sitters’ costumes and adornments, but from their humanity. It is in the sitter’s eyes that Catlin lingers.

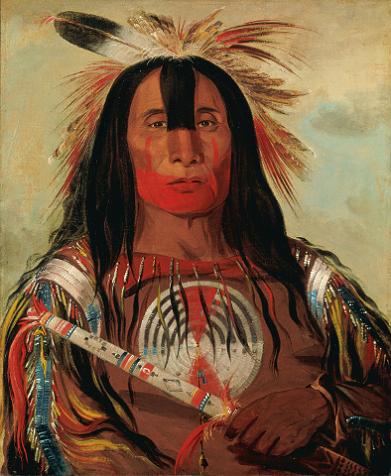

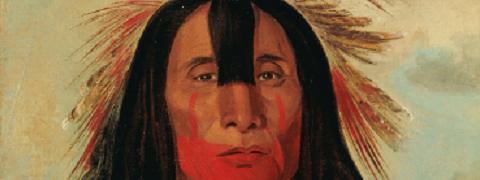

It is perhaps apt that the exhibition closes with Catlin’s two most acclaimed portraits of ‘Rabbit Skin Leggings’ and ‘Little Wolf’. Charles Baudelaire had described these as ‘noble’ at the Paris Salon in 1846 and their gazes are imbued with an ancient wisdom. One almost feels as if they are presented as a willed self-portrait in place of the image which we encounter as we enter the gallery – of Catlin dressed in Native clothing surrounded by reverent Western American Indians.

There is a quiet gravity in these portraits that is almost melancholic. There is a sense that, had he been standing within the gloom of the gallery, Catlin would have been relieved to have his work contemplated without the need for the flashes and bangs.

Here perhaps he has finally found the tradition which in life he was denied. What we question as we leave is whether the fact that this has been achieved is out of sentimentality on the part of the curators, or true admiration. Just as Catlin’s memories are of dubious authenticity, perhaps only time will tell.

George Catlin: American Indian Portraits runs until 13th October at Birmingham Museum

For further information and special events see the museum website

Quotations:

1: http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/jun/01/consolations-forest-sylvain-tesson-review

2: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2013/jul/21/mass-observation-photographers-gallery

Images: © Smithsonian American Art Museum

Any representation, visual or otherwise, of course reveals equally as much about the interests of the producer as it does the subject. Like Catlin finding his way through the Western American frontier during the 1830s based upon boyhood fantasies of being a wild Indian, his classical education, and his desire for reputation building, I consider his work and this article from my own set of personal and professional interests, faults and proclivities. As a Kiowa and Osage person who has studied art history and is familiar with 19th century images of Native Americans by non-Natives, I am struck by Catlin’s ability to individualize the facial features of the various tribes he painted during a time when that kind of immediacy was not always the case. In order to accomplish that, he had to be present and have a measure of respect for the humanity of the other person. In this, Catlin is quite unique and anachronistic.

I was also somewhat puzzled by the remark about the Native American subjects who “gaze defiantly out of their frames, seemingly unaware of their impending total eclipse in the new dawn of mass colonialism.” Is this hyperbole? Irony? Does the author think that we are gone? Because, guess what? We are still here. I know descendants of one of his portrait subjects for which the image resonates because quite simply it looks like people we know today.

I am not suggesting that Catlin’s project wasn’t exploitive, uneven in quality and romanticized and kitschy, because it was. But it was not just that. Within that mixture of contradictions, exploitive acts, personal desires and career disappointments, Catlin managed to create a remarkable body of work that can be understood as a complicated tribute to indigenous Americans of the early 19th century in addition to being an attempt at personal monument building as the article suggests. To propose Catlin’s project as a kind of alternative portrait that mirrors the desperate and gloomy psychological state of a disappointed artist, represents our current interests in self-reflexive post modern analysis and perhaps says as much about us as it does Catlin’s work.

Hi Marla,

Thank you for such a considered response. I would firstly draw your attention to the paragraph:

‘It is not, however, a sense of an inflated ego that one carries away. Rather it is an affecting impression of a man and the affinity which he found with his subjects, though always remaining on the outside. Most notably the portrait of a ‘Pretty Girl’ betrays an enchantment on the part of a painter whose paintbrush accentuates and fixates upon the ‘bright silvery grey of her hair’. Catlin is at his best when he captures this moment of alignment with the sitter.’

I think this acknowledges the fact that in spite of all the kitsch and romanticizing, he did clearly have a connection with his subjects that comes out in his work.

In terms of a psychological portrait, I think his methodology (in trying to be an expert in too many areas) and the farcical nature of the performances in Britain, testify to a body of work from which we cannot detach Catlin’s ego and, self-awareness. It certainly shows, as discussed, in the deterioration in quality of some of the paintings as the quest for, what you refer to as ‘a remarkable body’ takes over.

The artist’s hand and self are always evident in any portrait as you say however, there is no denying that, despite the admirable nature of the project- there is a little too much of Catlin’s face for it to be the scientific anthropological evidence that he intended. On the other hand by attempting to acquire the body of evidence that would make it so, some of the beauty seen in many of the portraits, suffers.

Hope this clarifies a few things in my argument.

Best

Francesca