‘I see the art as me wringing the sponge. And I’ve got a lifetime of sponge work to do.’ — Turning to painting to make sense of a world of hurt, Greg Bromley found the truth of pictures painting a thousand words. The artist speaks to Robert Horvitz to unpack his story.

Robert Horvitz (RH): Let’s start with how your work evolved.

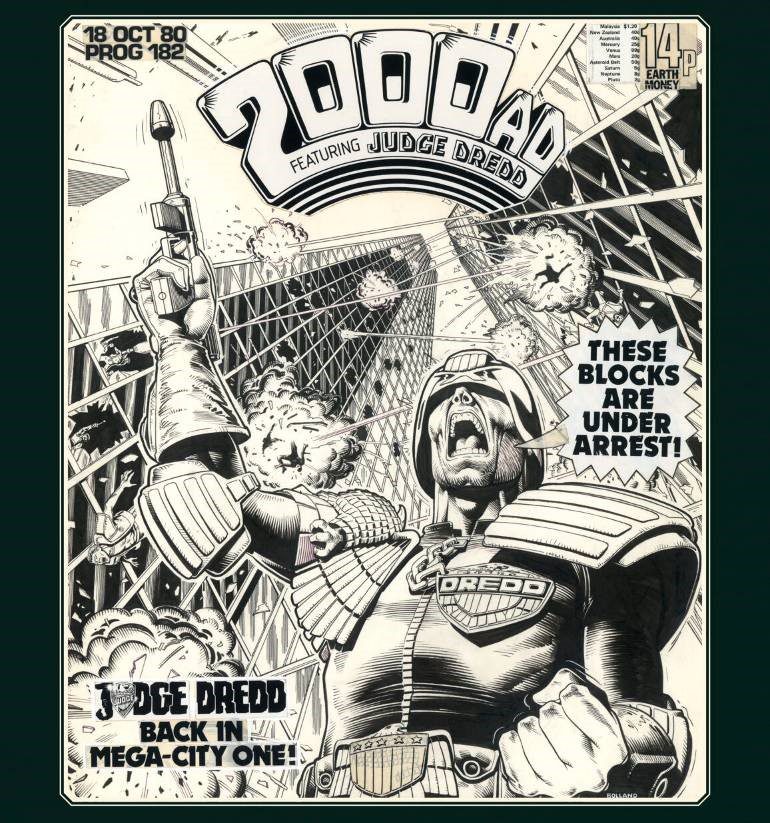

Greg Bromley (GB): Okay. I doodled as a kid. My grandfather used to bring me reams and reams of paper from work, with printouts on one side that were blank on the other side. I was eight, nine, ten years old. And I would just sit and draw space battles and creatures and aliens, children’s stuff. I would disappear into my own cosmos. It was self-soothing. At that point in my life, I found my first artistic influence. Have you heard of a British comic called 2000 AD? You must have heard of the character Judge Dredd. It was brilliant.

I’d read the comic and draw my own version. The pictures were often sequential: I would draw one scene, and then its continuation or aftermath. That’s how things started for me in terms of making art. What I remember is that it let me disappear from the humdrum of life.

I come from a working-class city. I wasn’t surrounded by any art people. I didn’t go to art school. I trained to be a social worker and qualified in my late twenties. It’s a very difficult, very stressful job. In my 23 years as a social worker, I experienced quite a lot of vicarious trauma. Other people’s trauma becomes part of you. I had a fairly high functioning career – job. I was a team manager. But I was like a sponge, a metaphorical sponge, that was completely soaked in other people’s shit, and I just couldn’t wring that sponge. Then in 2011 my dad died. Two years later, I had to step out of work because my brain was fried. I wasn’t coping. That’s what drew me to make art. I see the art as me wringing the sponge. And I’ve got a lifetime of sponge work to do.

When I was off work I got some big sheets of MDF [Medium Density Fiberboard] and started making huge detailed black and white drawings of made-up creatures. I don’t really know why, except that it harked back to my childhood, when I disappeared into drawing. Each panel took a couple of hundred hours – about three months.

RH: Do you still have them?

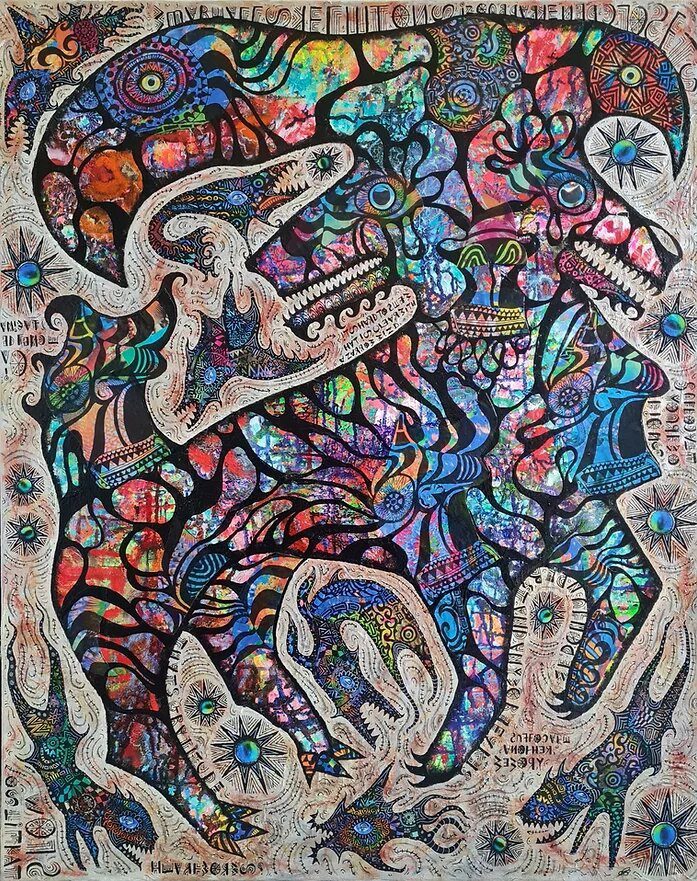

GB: No, not anymore. I’ve moved around a lot and things used to go in the bin. I was messing around with paint, too. No formal training, so my early paintings were very expressive. Abstract. Colourful. But nobody wanted them. So I started cutting up photos – giclee prints – of the paintings and printing them to make collages. Then I started drawing on the collages. I learned a few layering techniques, and techniques that allowed me to shapeshift older paintings into more evolved figurative expressions. Characters and creatures seemed to emerge from the shape-shifting process as I got further away from the original painting. The addition of collage let me go places I might not have gone of my own volition. I cut a flat colour in a figurative shape from an old giclee print, then I will start adding more collage on top of that. Then I will fill the background. I will cut in the main character and some of the lines around the characters. And then I will draw on the collage with Sennelier iridescent oil pastels, applying hairspray to set it and then adding a layer of gloss sealant. Then I will start working on top of that with more lines and more collage, figure out where it’s going, then I add the writing. Put more sealant on top of the background, then it’s the lines again, then it might be more writing, more sealant, just keep adding layers. I have quite small paint pens that I can use to add final details. There’s usually five or six layers of sealant on each piece, so the finished articles are quite something to behold physically.

RH: Are they mounted on boards?

GB: No, they’re on heavy-weight cotton paper. Most are small. A3 size. But all the layers and sealant make them stiff. David, who’s my main collector in New Jersey, is reluctant to frame them, because he likes pulling them out and feeling them. He really likes their tactile quality.

And they smell nice, because of all the hairspray.

I qualified as an art psychotherapist last year, and I was in therapy for two years during the training. I made a lot of drawings during this time. They were all quick pieces done whilst I was finishing some psychotherapy modules or personal therapy. Each drawing probably took about 30 or 40 minutes. They really helped me focus.

RH: How did that affect your practice?

GB: It was a real challenge doing a master’s degree at the age of 48. But I wanted to up my game. Being in therapy for a couple of years sharpened up my mind, in terms of who I was and how I was, and that just rolled in to how I made the art. I took more care. Concepts became clearer, I was more observant of the paths that I was taking and those I was rejecting. It gave me a better critical eye. And it was also significant that I was with people who had a predisposition to make art. I’d never been around art people before. And working smaller became a big deal. I’m working on a variation of the paper size A3 and I’ve gotten to a place where I am able to work a lot quicker. That took 13 years of experimentation and learning from dead ends.

Because there’s so much going on within the characters, so much detail, I tried to bring contrast into the image by making the background less busy. But over time it’s developed its own life. It has an element of ‘horror vacui’ where every space is filled. But even as I’m filling the space, I’m trying to create space, if that makes any sense. There’s a lot of arrows and wavy lines that I make with a black paint pen. I’m trying to get a lot of movement going on in the background where it’s like in a liminal space. “Liminal” is overused but it means neither here nor there. I think that’s how we exist. We exist in this bizarre, neither here nor there, abstract environment. That is absolutely mind-blowing and way more interesting than any landscape.

And then I have words going around the characters. It’s not just random letters. Put them together and they always spell out words. That has become increasingly important. It adds something to the abstraction of the characters. I used to believe that the words are there to draw in the viewer, to challenge them to extract the meaning, because the words make sense. It may look like gibberish but it’s not. But then when I look at the deeper reasons why I do it, I think it goes back to the experience of words failing, when I couldn’t express myself. I reverse and invert letters – break language into particles, like collapsed speech bubbles. All that’s left is a residue of felt meaning. Being a social worker, you often have difficult conversations with people, or are verbally abused, or threatened, and you try to understand how you’ve become a consequence of your experiences. It becomes a struggle for identity. That’s what the shape-shifting represents. I’ve thought about that quite a lot. Most of my characters are morphing. They’re unstable. They seem quite distressed, threatened or threatening. By illustrating these trauma narratives, I make it an epitaph instead of being in it.

One of the reasons why I semi-encode the words is because I want people to know what the picture is about, but I don’t want to make it obvious. If you’re going to look at the painting, you need to work for the meaning. There’s hurt in those paintings but I’m not interested in signposting why.

RH: The words pop into your head when you draw?

GB: Yeah. As the painting starts to take shape, words start to emerge. When I make an image, I listen to a lot of music and I have a lot of thoughts, obviously. I listen to aggressive heavy music, and I tend to mishear lyrics. Or something in the music might start my brain bubbling, and then it’ll become something else. Or I might be listening to a podcast. Do you know the physicist Sean Carroll? I listen to a lot of theoretical physicists like Sean Carroll, Tim Maudlin, David Albert. So I’ve got all this stuff bubbling and then words will start to manifest. I don’t plan the work, it just emerges. It’s a compulsion.

Titles are the dessert, if you know what I mean, in terms of finishing the painting. That’s the fun bit – coming up with the title at the end. It can come from what I’ve been listening to, what I see in the image and books I’m reading. Wordplay. I’ve certainly gone down that rabbit hole of quantum mechanics and the suggestions you can get out of all those really far out concepts. But I guess the narrative always will be carried by characters. It’s always going to be figurative.

https://www.instagram.com/greg_bromley_

After writing feature articles for Artforum in the 1970s, Robert Horvitz joined Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth publications in 1977 as art editor of their magazines before relocating to Prague in 1991. He has exhibited his drawings at museums and galleries in Europe and the US, including MoMA in New York and Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art.