[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]W[/dropcap]yndham Lewis attempted to reignite the flame of Vorticism with Group X in 1920¹ but lacking direction and co-operation from all participants it never got off the ground.

Lewis commented:

But what could be done with an X? Art at the cross-roads? X marks our goal? No. X refused to co-operate. Group X set out, but got nowhere. X marked our beginning and our end.

– Wyndham Lewis and the Cultures of Modernity edited by Dr Nathan Waddell, Ms Alice Reeve-Tucker.

It’s not simply a matter of dispensing with Lewis and Marinetti, they both offer a great deal in terms of the work they championed and in the work they produced. It is Lewis however, with his aggression and potency as both a writer and a painter, who offers an interesting model for modern artists. Lewis was unsentimental, delighting in upsetting his contemporaries and provoking his audience. Sentimentality, as Oscar Wilde observed in De Profundus, is a state where “One… desires to have the luxury of an emotion without paying for it.”

He (Lewis) was also intelligent and creative. He wanted to be serious and subjected his contemporaries to criticism, the missed opportunity of a closer and more collaborative relationship with people like Rebecca West and H.G. Wells is unfortunate, they might have improved each another.

There are tantalising hints that an appetite for just such a blending of extremes might be written into the very text of ‘Blast’ The illustrated Manifesto. Featured in ‘Blast’ is the statement: ‘We discharge ourselves on both sides… first on one then on the other’. It seems this potential was never fully realised, the respect and friendship of characters like West and Mitchison, along with ambiguous statements, is as far as it goes.

This is as much actual contradiction Lewis can contain within himself. When Lewis encountered Marxist ideas, even those diluted in the welfare state, he was openly disdainful and saw Marxism as a ‘sham’. Lewis writes critically of left leaning politics in ‘The Art of Being Ruled’.

Lewis had a similar relationship with feminism it seems. Wherever he detected resentment he was disdainful, which means that despite his support of female artists and his friendships with left-leaning activists, he is often remembered as the man who said things like:

If you do not regard feminism with an uplifting sense of the gloriousness of woman’s industrial destiny, or in the way, in short, that it is prescribed, by the rules of the political publicist, that you should, that will be interpreted by your opponents as an attack on woman.

– Wyndham Lewis, ‘Family and Feminism’, 1926

While feminism does contain contradictions and inconsistencies which have become more pronounced over the last fifty years², and despite activists and friends of Lewis saying things like: “I myself have never been able to find out precisely what feminism is: I only know that people call me a feminist whenever I express sentiments that differentiate me from a doormat” (Rebecca West, ‘Mr. Chesterton in Hysterics’ 1913) Lewis writing in 1926 must have seemed deeply unsupportive to the wider public’s (woman’s) struggle with sexism. His disdain for the public and the ways they transferred ideas into practical action, his disapproval of revolution as something ‘dull’, and his use of the family as a symbol to beat the feminists with was divisive, knowing that this strategy would garner support for his critisisms with the sort of traditionalists (mainly men) he otherwise repudiated!

Lewis has, however, a shockingly modern voice:

With a new familiarity and a flesh-creeping ”homeliness” entirely of this unreal, materialistic world… all ”sentiment” is coarsely manufactured and advertised in colossal sickly captions, disguised for the sweet tooth of a monstrous baby called ”the Public,” the family as it is, broken up on all hands by the agency of feminist and economic propaganda, reconstitutes itself in the image of the state.

– Wyndham Lewis.

Up until the last two clauses Lewis is correct isn’t he? He could be talking about our own society with its schizoid projection of images: adverts, charity appeals, dramas, comedy, the news, all smashed into the face of a person watching an hour of television in the 21st century. Each component assumes a false equivalence, appeals for money to save dying children one moment, the next an advertisement for coffee!

Achieving nothing and propagating apathy or, worse, glib sentiments, the fact that Lewis directs the blame for this to feminism is a limitation of his time and reaction, rather than good explanation of the problems he describes.

Read previous essays in this series: Part One ¦ Part Two ¦ Part Three

¹A group of British artists formed in 1920 that showed their works at the Mansard Gallery, at Heal & Sons, London, between 26 March and 24 April of that year. The core of the group was made up of the former Vorticists Wyndham Lewis, Jessica Dismorr, Frederick Etchells, Cuthbert Hamilton, William Roberts and Edward Wadsworth. They were joined by Frank Dobson, Charles Ginner and McKnight Kauffer. The exhibits in the main were characterized essentially by a propensity to angular figuration not far removed from other experimental styles of the period. Group X was arguably an attempt by Wyndham Lewis to revive Vorticism, but this failed. – Note from the Tate archive

²I am thinking here of the difficulty traditional feminism has had incorporating other cultures whose traditions are offended by the implication that they might be sexist. Also the difficulty encountered when traditionally exploitative roles such as prostitute or stripper are declared empowering for certain woman who have become wealthy and independent of men as a result. These ideas can be traced in looking at ‘post’ feminism.

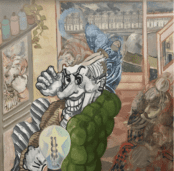

Michael Eden is a visual artist, researcher and writer at the University of Arts London exploring relationships between monstrosity, subjectivity and landscape representation.