[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]ncluded in Trebuchet’s Time and Space issue, Hatice Besun’s photography is an investigation into existential and ontological questions: what is now, and what is the consciousness through which we perceive the world? Her photographs capture the pale light of endless bleached, late summers. By pushing the perspective horizon beyond its limits in her work the viewer is transported into a dreamland, where everything is simultaneously scene and actor, protection and threat, potential and past.

Besun’s work to date has been largely abstract in nature, however life can intervene and force you to react, regardless of your erstwhile intentions. On 1 December 2016 while living in Turkey, her world was revealed to her in a stark and inescapable way.

Look, Hatice Besun (2016)

Describe the events leading up to you discovering the bodies. Did you know they would be there?

At the time, I lived in a house by the sea in Urkmez, Turkey. One morning my neighbour knocked on my door and said, “Wake up!” She said that on the beach were dead bodies, and in the water were Syrians swimming away from the boats. I quickly walked to the seaside and I saw the first body on the beach about 50 metres away.

I was shocked. I froze. The sea was stormy.

I noticed another body to the right of me, and another on my left. There was nothing I could do. When I looked at the body in front of me, the features were already decomposing and unrecognisable. There were very few people on the beach at this point, no police or soldiers yet.

What was your first reaction to the bodies?

My first reaction was a reflex; I thought that I should take a picture. I ran back home and got my camera. My hands were shaking. I looked at the framing, I did not like the angle. I pressed the shutter repeatedly. I was focused on the aesthetics!

I was shivering, crying, and looking for an aesthetic way to present this awful scene. Coast guard officials began to arrive. I then photographed the other bodies that were washed up on the beach nearby, thinking that the coast guard officials would soon not let me continue photographing. Then I went back to the first body I had found. And for a moment I really saw him clearly: on the beach among the lonely waves, hope dead, skin torn, no face, no identity, just a decomposing corpse. The sea smelled of death. I felt great pain then, as if I was looking at myself washed up on the shore. And at that moment I looked at the camera in my hand… and I saw the monster inside me… and it was like I caused his drowning somehow, like I did this evil deed and so was the one who was exposed to it and saw it up close.

I said to myself, “What am I doing here now?” I was stuck again. A stormy day for me, a person who runs away from those who put their lives at risk to flee cruelty and persecution.

See, Hatice Besun (2016)

How did other people react to the bodies?

Everyone was scared. They felt that they were sacrificed there. People around me told me to give the photos to the newspapers but my answer was clear: no, I was not a journalist. I left my house for about a month to clear my head. I was very traumatised by the whole thing. It was, I saw them, they saw them.

As an artist in what context do you place these images? Portraits? Landscapes? Did taking the photo allow you to connect or disconnect with the event? And has that affected you?

Photography is essentially a documentation of human existence, a fact that tells the small history of a moment and the period from the photographer’s perspective, of course. Roland Barthes says in his great book Camera Lucida (1981): “I observed that a photograph can be the object of three practices (or of three emotions, or of three intentions): to do, to undergo, to look.”

If we drop the notion that the photo objectifies the subject, the subject observed in a photograph of death is the object. The photographer is the operator here, alone. The control is fully operational, like today’s selfies.

Returning to my experience again, in the face of an unexpected situation, I witnessed it here at the same time. It is arguable to look at the event from outside or watch the photo taken before the photo is taken. My point of view here is the one and the whole that is observed, observed and operated. The victim who suffered is inside of me.

How am I doing? Savaged. Alone and gone. The monster inside me, cruel. The right to life for others, and the order of death. The witness watching what happened, briefly persecuted, watching what happened (the witness who did nothing). My experience was: to see that I am all three!

If we look from an outsider perspective, people who flee from power and control and fascism hoping only to live humanely, the result is a lonely anonymous death. We do not want to see that it is our responsibility. I, and the world, perceive it as separate. Unfortunately mankind is doing this to his own kind, to himself.

Here it is, Hatice Besun (2016)

How did you find the confidence to use these photos?

I kept these photos in my archive for about three years. It was very important for me to figure out if taking them was ethical or not. And I wasn’t ready for that. Today when I re-evaluate my past decision, I remember that the identity of people in the photos is not clear; they had no faces. This is somehow very important. Also, the photos must not be used for mainstream pop magazine industry purposes. They must not be used for people’s atrocity fetishes. I trust Trebuchet magazine in this regard.

The photo tells the story itself. I believe it. The photographer should not talk much about the photography. The artist has already explained himself in the photo. The message is clear from the photographer. But for the audience, of course, this is all semantics. Since I felt a lot of responsibility for the use of these photos, I needed the message of these photos to be clear to me before bringing them to the public.

I believe artists must be brave. Maybe people who see these will not like them, maybe they will not think them ethical or moral, maybe this will affect my photography career negatively.

But, after considering all of this, it is clear to me that the message of these photos is well worth the risk. We forget too often that the world is you and it’s your responsibility! Hence the name of these photos from Camera Lucida: look, see, here it is!

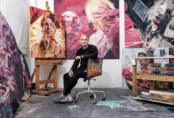

Hatice in Trebuchet 6: Time and Space

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle