Hyper-production, designed obsolescence, information overload, taboo-breaking, the ‘meme-ification’ of history, rapid technological and cultural innovation interacting synergistically with populism.

We’re all familiar with these aspects of our present reality, yet from what materials were this landscape sculpted?

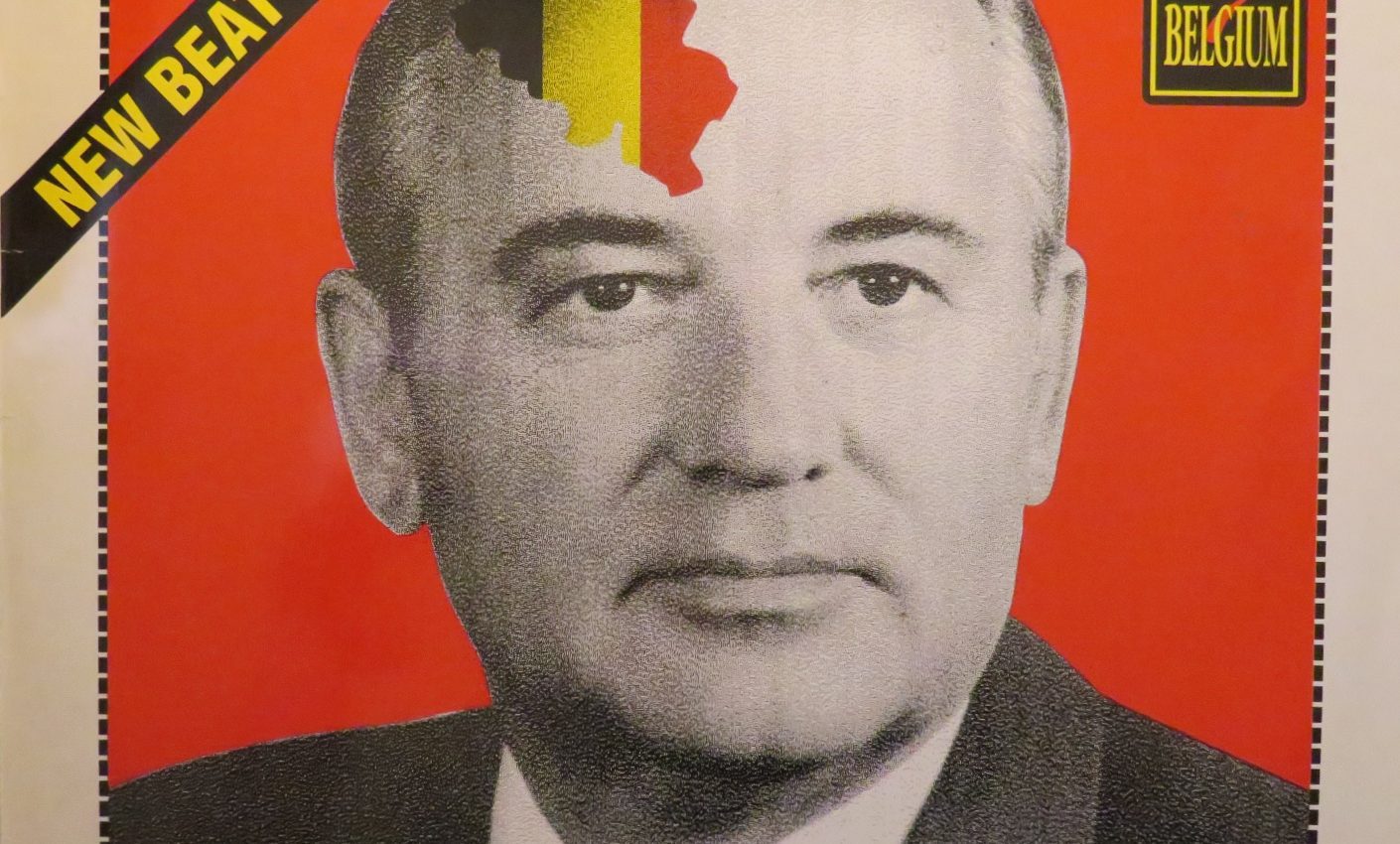

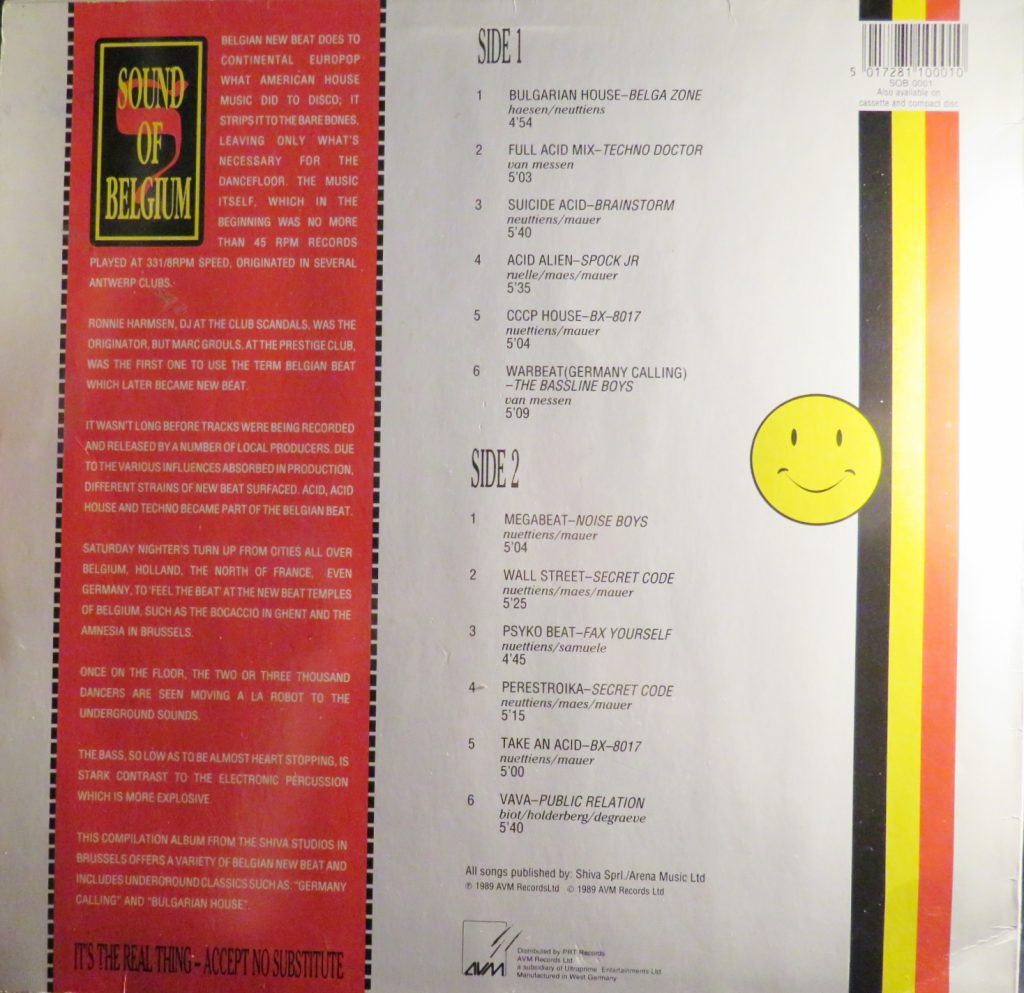

In the late 1980s bemused, almost incredulous reports seeped into the British music press of a ‘new beat’ emerging from Belgium, which playfully used history as just another cultural commodity to dance to. Produced by factors including a record being put on at a wrong speed that turned out to sound very right (“Flesh” by A Split Second) and a previously unserved need amongst Belgian youth for a local dance music of their own, new beat is remembered both for its influence on early techno and for the shameless trashiness powering much of its success. It served as surprising prophecy, social and technical commentary and cultural novelty. The most innovative tracks refined the use of ‘acid’ 303 sounds and, most radically, the combination of hard, compellingly danceable beats with unprecedentedly low tempos (typically 95–110 bpm). It fused unashamed Belgian hedonism with technical innovation and rapid production. At its peak, one multi-aliased production trio recorded 100 singles in a year. (Klein 2014.)

It succeeded another innovative Belgian dance genre: the ‘electronic body music’ (EBM) associated with groups like Front 242. New beat largely dispensed with EBM’s dystopian and countercultural mode in favour of borderline pornographic, hedonistic and humourous samples. As a provocative sales strategy, this worked spectacularly, ensuring hits were blacklisted by local media yet sold in huge numbers. Even after it became a mass phenomenon, the only regular place on the Belgian airwaves for it was Antwerp radio show Liaisons Dangereuses.

Some producers used history and politics as improbable dancefloor materials. With hindsight, such tracks seem to have signalled the shift to our post- or multi-historical society. If such an aggressively innovative and tasteless genre emerged now, it would be labeled ‘disruptive’. Tracks like Export’s “Pearl Harbour” which forcefully conscripted sensitive historical material as provocative entertainment were a symptom of a culture letting its guard down. Although with that war four decades in the past and the more recent Cold War thawing, it’s possible to see how the producers felt so free to play. In what other time and place but late 1980s Belgiumcould there have been a succession of hits dealing with World War II or the French Revolution?

New beat’s peak coincided with the Revolution’s bicentenary and naturally the genre responded. République’s 1789 made up for the lack of historical audio with samples of “La Marseillaise” and films about the revolution, plus acid sounds, martial drums and hedonistic house piano.

The most controversial example of new beat’s flippant attitude to mainstream history was 1989’s “Warbeat (Germany Calling)” by Belgian act The Bassline Boys. One of the hooks was the infamous call sign used by Lord Haw-Haw (William Joyce) in his pro-Nazi wartime broadcasts. (In 1987 German act Voyou had already used a sample of Joyce on a proto-techno hit.) “Warbeat” used samples to condense the story of World War II into a frenetic dance track fuelled by a brutally insistent acid sequence. Churchill and Eisenhower samples were augmented by a cartoonish vocal announcing “Adolf! Adolf! You’re going to pay!” However, it also featured a Hitler sample and an aggressively syncopated “sieg heil!” which some took as a celebration of Nazism, despite the cover artwork featuring an unhappy looking Hitler caricature surrounded by predatory Pac-Man type characters. A tradition evolved out of outrageous club PA appearances and in April 1989, a troupe of erotic dancers performed to the track wearing customised uniforms with mock swastikas made from black tape placed over their nipples and acid smilie insignia on their peaked caps. Some of the audience responded jokingly with Nazi salutes.

This was the logical end point of new beat’s very Belgian war on taste, and for those in on the joke it had no deeper significance. Dancer Christine D even stated that it was “absolutely anti-fascist” and pointed to its success in Israel, while others argued that it satirised Nazism. (Colard & Berger & Matura & Bonjean, 1989.)

However, when it was played at a French club and Nazi salutes were given, a scandal erupted. The combination of alleged Nazism and drug use fuelled a perfect storm of moral panic on a French TV report about the scene, which was already infamous in the Belgian media. Yet like punk, condemnation made the track more successful. The programme’s refusal to allow a right of reply or clarification led to a Bassline Boys response track sampling the condemnation, which also became a hit. “On Se Calme ( Scandale Mix)” featured looped and comically cut-up extracts of the denunciation and the presenter’s surname, followed by the original’s ‘you’re going to pay’ sample. This playful sequel demonstrated how new beat revelled in its outlaw status.

New beat also put its offensive stamp on more recent and even contemporary history. Its attitude informed a series of hits based on the kidnapping of former Belgian prime minister Paul Vanden Boeynants…

From Speak and Spell to Laibach.