Holly Hendry’s sculptures interrogate our bodily experience of space through a variety of materials and forms.

For her latest solo exhibition Indifferent Deep at the De La Warr Pavilion in East Sussex, the artist has “chomped” through the ground floor gallery’s walls to create a half-eaten space within which her sculptures are arranged while a new public artwork, entitled Invertebrate, burrows through the building’s rooftop and balconies, emerging on the lawn outside.

Here, Hendry discusses the starting points for the works, responding to the local landscape and her interest in processes of consumption.

Scientific research, experimentation and drawings seem to inform many of your sculptures and installations. What draws you to the scientific field and specifically, to discoveries of past eras?

I think it’s because I have such a practical approach to my works, where the investigation comes through material manipulation, but in a lot of ways it’s entirely opposite to scientific investigation because my work meanders and moves in a lot of different ways.

In terms of the past, I tend to think about how past discoveries are relevant now. I’m interested in the cycle of things, things that repeat themselves and how we learn from them. One of the starting points for the De La Warr show, for example, was thinking about hunger stones, which are these objects that they have just started reappearing in the Czech Republic. They act as a kind of hydrological landmark, marking water levels. But they also have inscriptions on them and one translates as if you see me weep. It’s sort of like a warning to future generations, and it was something that was put into water thousands of years ago but feels so relevant to now.

What’s your typical development process for creating a new series of work or an exhibition?

My work has a lot to do with space or environment in terms of how people use a space or how it’s come about. So an idea for an exhibition usually comes from spending time in the space and trying to understand my relationship to it in parallel to my own research into whatever I’m thinking about at that time. Then the idea gets translated through the making process. I use my studio as a space to test materials and try new combinations. I then draw the space on the computer or in my sketchbook and try to manifest these tactile things with shapes and forms. It goes between moments of total chaos and not knowing and working it all out in a practical sense. With this show, things changed a lot because of the pandemic. I was first talking to Tamsin, the curator for England’s Creative Coast and Rosie, the curator at the De La Warr, about these works in 2018, but some of the materials I’ve used came about because of the pandemic and also the physical space changed a bit.

Which materials are you talking about in particular?

So in the exhibition, the floor and some of the walls are coated in MDF and that came about because a lot of building projects were being cancelled or totally scrapped because of the pandemic and there was all this leftover material. I met a builder who told me about the situation. When I mentioned I was a sculptor, he said to go and see the material and it became apparent that they were trying to get rid of hundreds of sheets of MDF so they basically donated to me. I felt kind of uncomfortable and worried about it initially because I’m always very aware that in creating sculptures, I’m putting more stuff into the world, but it echoed a lot of what I had felt spending time in Bexhill and that area of the south coast and seeing the brickworks and massive kilns where they make bricks. It made me think about the larger scale of the building industry, chewing up the land and spitting it out and rationalising it into forms that are then fired, but also the essential quality of that – these brinks are building homes which people need for shelter. To me, the MDF negotiated a similar opposition of ideas as it’s mulched up wood, that’s flattened out, squeezed into panels and rationalised into boards that we use to coat the inside of houses. And after the exhibition, this material will have an onward life as it will be donated to art studios and artists.

Where does the title of the exhibition Indifferent Deep come from?

I was thinking a lot about feelings of extreme sorrow and also numbness in the everyday sense of the building materials that I’ve used. The building itself is right on the edge of the coast, it’s very long and flat as a gallery space, and when you’re standing there looking out of the windows, you can see the line of the horizon and it seems like you’re on that line, so I was also thinking about an idea of floating. For me, Indifferent Deep spoke about those ideas, and implied a sense of depth as well as the unknown.

The idea of consumption or digestion seems to run throughout your work. What interests you about those processes?

I think it’s more about incorporation or transformation through consumption. Through the process of incorporating one thing into another thing, outlines and edges become blurred, reconstituted or renamed into something else, and that presents opportunities to undo or redo certain binaries. A really practical example is when you’re eating something like a crisp and then suddenly that crisp becomes part of your insides. A lot of what I try to do is to consider this dialogue of internal and external, and when or where those contours shift or end.

You’ve said before that you like to “challenge” your materials. Can you explain what you mean by that?

For me, there’s a real investment in trying to get to the bottom of why something feels or acts a certain way – the language of materials and why we’re drawn to particular things. So, if I can make plater become glossy or delicate or thin, or if I can speak about excess through a material which is very simple then that really interests me because I think by changing materials’ properties they can become something that registers space or people or tactility or emotion. It’s also exciting to challenge the materials and to see how far something can be pushed.

Are there any materials that you find yourself returning to?

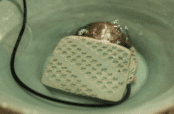

I’ve been working with silicone a lot recently, which feels quite hypocritical because as I said before I’m always thinking about what is used up and the sustainability of a material and process, although are more and more alternatives to the plasticky kind of silicon that doesn’t disappear for centuries. For me though, there’s cartoon malleability to silicon which I like, it can take on lots of different forms and I’ve been trying to make images with it and treating it like something flat even though it’s a mould making material that’s usually used to make shapes. I’ve also been using a lot more natural materials recently like sand and chalk and clay. I’ve used the sand a lot in the De La Warr show – it’s a material that erodes or breaks down, but it’s also the product of that process as well which I find interesting and again, it relates to those ideas of consumption. I use Jesmonite a lot because it’s a total shapeshifter, it changes it’s quality and surface depending on how you adapt it and you can add strange things to it such as food stuffs and it doesn’t crumble or go mouldy. I also like that you can add pigment to it and have these kind of really bright colours as well.

Speaking of colours, you often use quite a chalky or powdery palette. What guides your choice of colour?

Generally, I rely on processes to decide the colour. For example, with the plaster works, instead of adding proper pigments, I was just using household paints which meant there was only a certain level of colour it could achieve. When the plaster dried, it lightened and the colour became chalky or kind of sugary, almost sickly sweet at times. With those works, I was interested in the seduction of the pastel colours but using them talk about material breakdown or rotting. Recently, I’ve been using some brighter colours in a similar way to point at or highlight certain things.

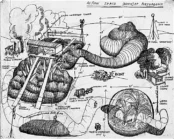

What was the starting point for Invertebrate? And how did you arrive at its form?

There’s this thing called the wreck of the Amsterdam, which is a shipwreck that appears around eight times a year, and I was lucky enough to see it once when I was in Bexhill and it’s this bizarre carcass that appears on the seafront when the tide is out. Also, spending a lot of time looking out to sea, I sometimes saw this kind of yellow line of pollution. Along with visits to the brickworks and the Bexhill museum, I started thinking about what it meant to be on the edge of land. All these things washing up, churning, and revealing themselves. The idea of a worm kept coming up as this thing that digs down, through edges and bypasses borders and I started doing research into earthworms and how they sink big stones from undermining.

At the time, there was also the impending Brexit situation and so these political borders were being put up. Within that, the worm became this symbol of how to break through those edges or how to think about different ways to navigate them. The work is intended to kind of look like an earthworm or some kind of gut and it’s made from things that are already from the surrounding area. The big red sections are made from techniques mimicking a standard kind of sandbag that forms flood defences on a domestic scale. Similarly, the cast sections are made in the same way that tetrapods would be made, which are sea defence methods that you can see further down the coast. There are also bricks that are from the brick works themselves and extruded metal parts that come from that architecture of building as well. I really wanted the work to reference the building too because I seeing how it was battered by the elements and being eroded.

What are you working on now?

Mainly tidying the studio – it’s extremely messy after these last few months! At the start of next year, I have a show with Stephen Friedman Gallery.

“Holly Hendry: Indifferent Deep” runs until 30 August 2021 in the ground floor gallery of the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill On Sea, East Sussex. Find out more: dlwp.com

Featured image: Holly Hendry: Indifferent Deep installation view. Commissioned by the De La Warr Pavilion. Image copyright the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery. Photo: Rob Harris.

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.