What does portrait painting hold for us in the 21st century? Caught between the tropes of wealth signification and identity politics is the weight of history too heavy for this genre to fly in the contemporary world? In attending the artist talk of BP Portrait Award winner Charlie Schaffer, exhibiting for the first time in four years with Charlie Schaffer: Scalpel-like Eyes, the challenges of painting a person come to fore. Who does it serve? What does it say? And what does a picture of someone mean in a world awash with personal image making?

By grappling with the omnipotent tension between his art and what it creates, Schaffer’s paintings transcend aesthetic and transform into statements of time, space and experience. The social and historical weight which meshes onto portrait art is something Schaffer toys with but ultimately abandons. Schaffer creates with the intent to evoke empathy rather than seducing the eyes.

Paramount to understanding Schaffer’s personal philosophy is understanding his disdain for labels, “…portrait insinuates the painting is showing something about a person… My paintings work on their own merit. It happens to be about people but not about them”. Here it is clear that Schaffer’s distinction between humanity and the individual. Such a manifesto welcomes a discussion on existentialist angst nature of all painting, but more so where an individual is the subject- remembering that Schaffer doesn’t consider his work portraits (see Trebuchet https://www.trebuchet-magazine.com/the-life-in-portraits-charlie-schaffer/). How should one go about relishing Schaffer’s art when it is rendered as a by-product of a relationship only him and the sitter access? When the given idea that all answers are congealed in canvas is objectified by the artist then the viewer is held in suspension.

Schaffer’s art demands the analysis of being over the analysis of technique, which resituates any dialogue about his work around people and not the mastery of his hands. He simply states, “technique and style are a means to an end” and that’s the direction the viewer must go toward. If Schaffer is ‘too involved and too separate’ from an emotional interpretation of his works, aesthetic judgment must be found in our own lives and experiences. You must shun the insularity London breeds and open all stimuli to the kindness and strength in community. In practice, this means Schaffer’s work, as a vehicle for his process, is an analysis of empathy.

That said, for someone who doesn’t care for images he is brilliant at the game of creating them. Schaffer’s skill proves the mental dictation of the physical and produces works of sublime revelation. This is the coherent theme throughout his pieces. Hairline brushwork, masses of paint and impasto strokes funnel emotional utterances onto all four sections: portraits of others, self-portraits, drawings and the old masters.

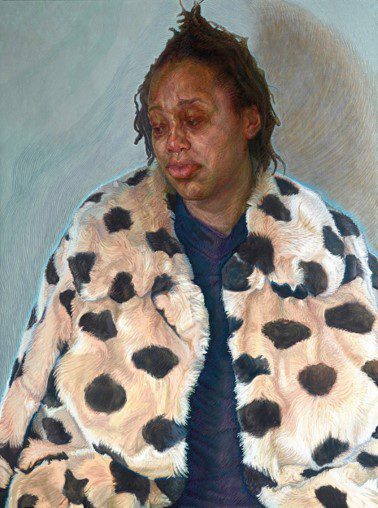

At the exhibition itself viewers are drawn to ‘Imara in her winter coat’ , his most famous piece which secured Schaffer the BP portrait artist award and subsequent recognition. The mild tinges of blue and Imara’s melancholic facial expression convey a powerful meditative empathy and yet Schaffer claims that it is crucial the sitter holds no value to the painting until finished. By suggesting that the “person sitting wants to be sitting”, Imara in her winter coat only records a fragmented state of being, in which a mutual therapy of sad engagement overrides any possible vanity of someone having their portrait taken for posterity.

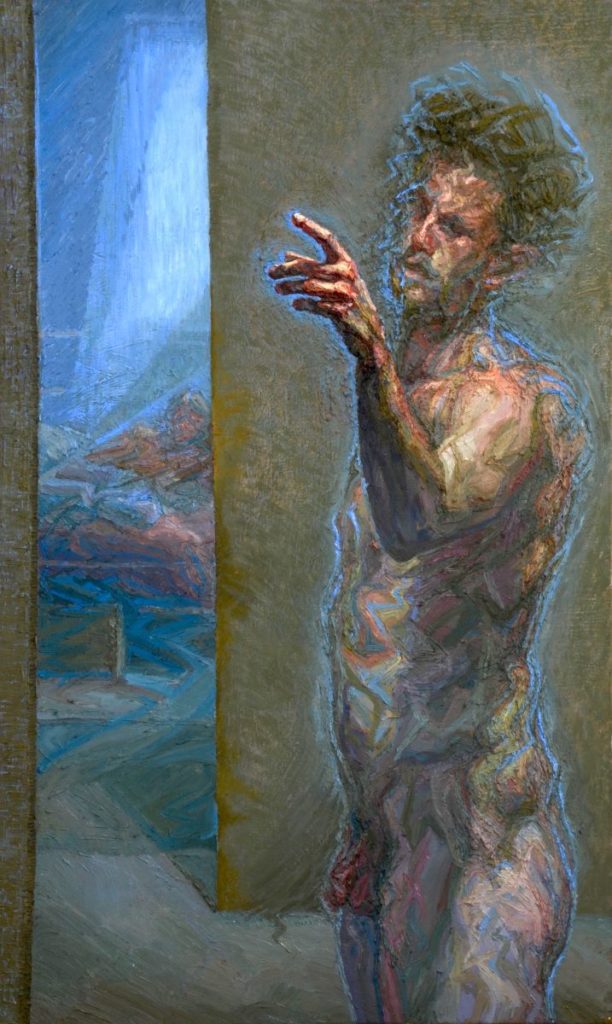

Schaffer’s ‘Self-portrait in Margate’ perpetuates his practice of artistic displacement as an event of being, over a purely aesthetic consideration. He disciplines the sitter (his own body in this instance) to exist in decontextualised time and space – using thick paint “purely as a way to get the back and front to merge together”. Existence and environment seem simultaneously tangible due to the mass of paint Schaffer’s self portrait uses. As the layering of the foreground onto the background is so prominent, the body looks as if it is trying to escape from the linen and oil that binds it. Perhaps this plea to escape the pressure of personal image making, conveys a contemporary state of the personnel.

The process of sitting for the portrait rather than its final outcome frames Charlie Schaffer: Scalpel-like eyes in utmost authenticity. Despite existing as brilliant entities, Schaffer’s work touches upon a tenderness innate in simply living. His art is merely a chamber of resonance which showcases odes to times gone by. To understand why Charlie Schaffer creates is to be liberated from life’s confusions.

Any viewer of Schaffer’s art cannot make the grave mistake of viewing his portraits as signifiers of wealth or nobility. Yes, there are strong conceptual components that make his work aesthetically incredible, yet what they truly capture is the shared creative space which makes the final result possible – the worth found in interpersonal connection.

Charlie Schaffer: Scalpel-like eyes Artist Talk at BWG Gallery (15 Bateman St, Soho, London) on the 27th May. The exhibition ran from 17.05.23-30.05.23

London based writer who graduated with a BA in English Literature and is navigating the trials and tribulations of their early 20’s. Her primary fascination is how art mirrors life’s complexities. When art is created, conversation ensues – thus creating an endless space of expression and thought. Each word she writes is an attempt to decode possible motivations of the artists desire. Her work is infinitely obsessed with the question that concerns every creative piece – why?