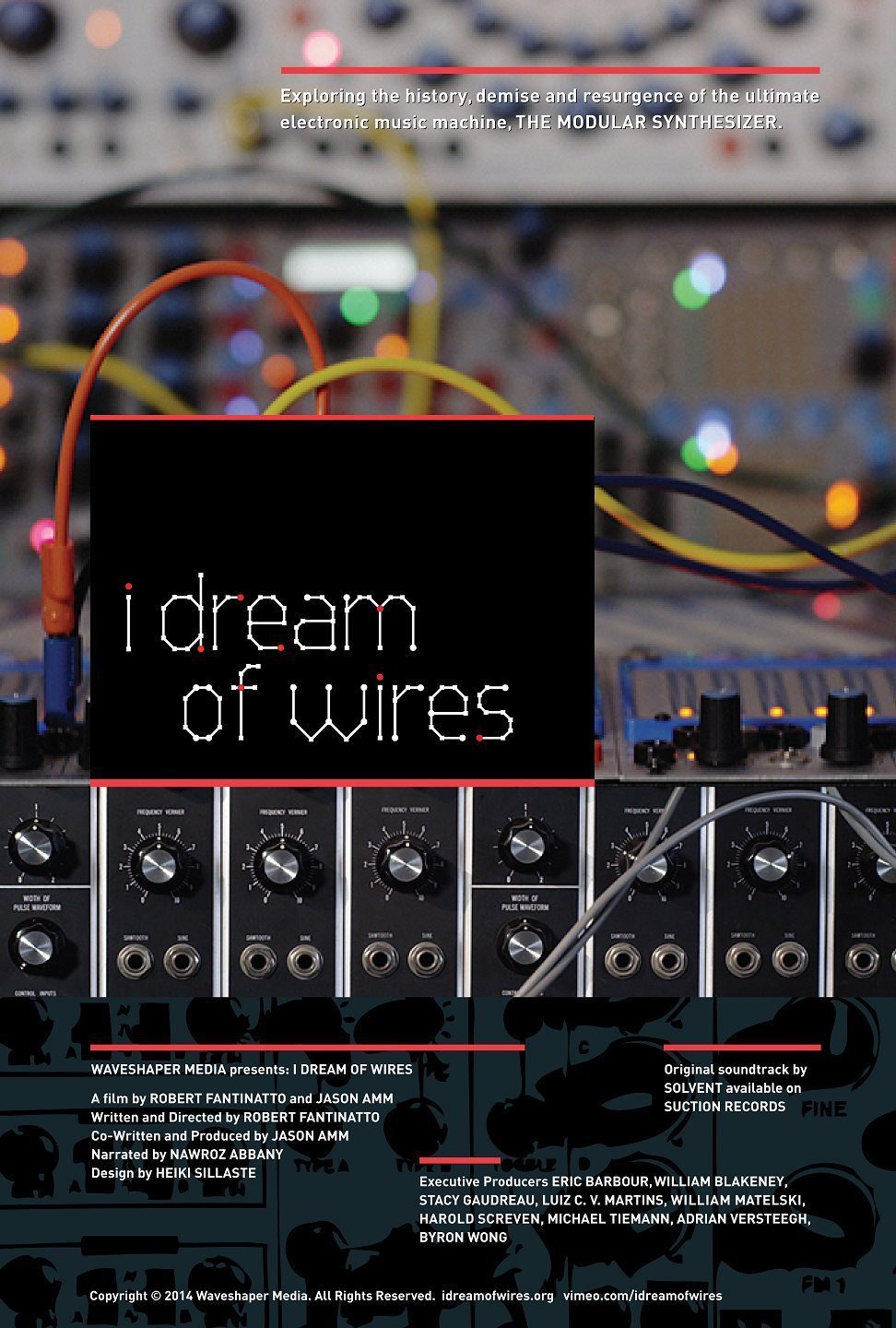

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]L[/dropcap]ike its subject, modular synthesizers, Robert Fantinatto and Jason Amm‘s I Dream of Wires is a phenomenon that refuses to die.

This is a new 90 minute theatrical cut of the original 4-hour Special Edition cut that was released on DVD and BluRay in late-2013. The original version has had a strong impact, but the new edit is designed to bring this chapter of electronic music history “to the masses” without going (too far) into the kind of technical depth that really is “strictly for the hardcore”.

With a stellar cast of contributors and beautifully-filmed close-ups of synths ancient and modern, the film could have easily have been no more than an agreeable fan film. Fortunately, it’s much more ambitious and presents a clear historical narrative that also touches on wider cultural and technological history from the dawn of electricity and the first strange electronic instruments created by Leon Theremin and others. Some parts of this story are well-known, but others are new and valuable and many of the interviews with the creators and the users of modular synths contain real insights. Canadian analogue producer Solvent’s soundtrack (available separately as an album) enhances the overall effect well:

The film moves through what can now be seen as the “pre-historic” period of electronic music, the age of colossal beasts like the RCA Mk2, still bolted into the concrete floor at the Columbia University Electronic Music Centre – housed in a building where Einstein and others worked on The Manhattan Project. The advent of the transistor at the end of the 1950s made it possible to build much cheaper and smaller devices. We follow the story of how

physics undergraduate Robert Moog started selling theremin kits but soon created “one of the most recognisable sound signatures in modern music”: the VCF (Voltage Control Filter).

One of the key concepts of the film is the clear division between Moog’s initially-dominant “East Coast synthesiser philosophy” and its West Coast equivalent associated with his Californian counterpart Don Buchla, who released his first machine a few months after, Moog although some claim that Buchla’s design was older.

If the East Coast scene was more institutional and industrial, the West Coast scene grew out of links with the Californian counter-culture (early machines were used at open-air happenings). Although as a former NASA engineer Buchla also had an institutional background, he soon connected with the free thinkers of the San Francisco Tape Music Centre who commissioned his early prototypes and turned down the opportunity to make money from their collaboration. Founder member Morton Subotnick is a charming and energised interviewee and explains this phase of electronic music well.

The biggest practical differences between the schools of synthesiser production were that the East Coast machines were more filter-based, while on the West Coast the focus was on wave shapers.

Moog machines did better as they had keyboards and fit the classical image of composition, whereas Subotnick had specified that the Buchla shouldn’t have a keyboard as he didn’t want to (re)-produce conventional music with it and Buchla continued to resist keyboards, instead developing the analogue sequencer, the full potential of which Subotnick demonstrated to him. The film compares the two breakthrough works emerging from the two sides, Walter Carlos’ Switched on Bach and Morton Subotnick’s more obscure Silver Apples of the Moon (which ironically was produced on the East Coast after his move to New York).

The film traces the emergence of new competitors such as the ARP 2500, EMS Synthi 100 and Roland 100M that arrived in the wake of the Moog and Buchla. It shows how during the course of the 1970s modular synthesis shifted from being available only to institutional composers or God-like rock superstars, to becoming accessible to the misfits and malcontents of the nascent industrial movement, strongly represented in the film by figures including Mute’s Daniel Miller and Throbbing Gristle’s Chris Carter, who discusses how he built his own devices and the hostility that electronic music produced, not just among the wider public but also from Punks. As John Foxx explains, synthesisers were associated with Pink Floyd and it took time for a more radical use mode of synthesis to become established.

We also hear from more popular figures such as Gary Numan and Erasure’s Vince Clarke before the film tracks developments during the 1980s, which the film tells us “were a dark time for modular synths”. With the advent of digital synthesisers and the Fairlight, the huge modular devices returned to the academic studios they had emerged from and for a time others were even dumped or sold off for scrap (something hard to imagine now that originals go for astronomical prices). Daniel Miller talks about the period in the early-mid 1980s when analogue was in the full-on retreat, a process halted by the advent of acid house and techno, forms that often prized the rawness of analogue.

The views of Meat Beat Manifesto’s Jack Dangers are also interesting and the scenes in his Hilltop Studio provide a hardcore dose of gear porn. Dangers dates to 1993 the first time the word ‘vintage’ was used in relation to synths. This illustrates how the film flows between social, musical and technical history, often drawing out precise turning points in the history of modular synthesis and the music it continues to generate.

Yet it was just as the original synths became ‘vintage’ that a tentative revival began, gradually spearheaded by figures such as Dieter Doepfer, pioneer of the compact and affordable Eurorack style of devices. From 1998 onwards new machines were again produced. Like their counterparts they were initially expensive but have become ever more accessible and popular, spurred on by an active scene of enthusiasts trying to enhance and extend the classic devices (which as Jeff Blenkinsop of The Analogue Lab reminds us are increasingly difficult and expensive to maintain). This part of the story is a chance for contributors such as Trent Reznor to castigate laptop production and pre-set sounds and welcome the revival that is “re-introducing the magic lost with Rolands, Korgs, Yamahas … scratch sample bullshit”.

For me, moments like this feel a little unbalanced – the fundamentalist assumption that analogue is always superior to digital is never questioned and I know from my own listening that, while I love the work of many of the film’s contributors, music produced by digital means can sometimes be more aesthetically satisfying than analogue-produced music.

Ultimately, bad music produced on a specialist custom-built modular synth is still bad music, whatever its retro/innovative/organic analogue credentials.

The film ends in the present day “modern day modular renaissance” – a time when there are at least 45-50 manufacturers (often collaborating actively with artists) and numerous events for enthusiasts who, as more than one contributor remarks, can rapidly become addicted. Vince Clarke cautions that at some point “you’ve got to stop buying stuff and start doing stuff” and techno producer Drumcell observes that having a space limit is good as a means to contain the addiction. Other contemporary artists including Orphx, Container and Clark praise and demonstrate the current technologies (sometimes in tantalisingly short live clips).

The film concludes reproachfully that “we let the modular slip away from us too quick to embrace technologies of comfort and convenience …” yet still asserts that we’re now entering the true Golden Age of modular synthesis.

By the end of the film the West Coast philosophy of pure, keyboard synthesis seems to have won out, yet in recent years keyboard-equipped devices such as the Korg MS-20 have been upgraded and revived and while modular devices may be perceived as purer or (dare I say it) hipper, I’m less sure that this is a final (or even inherently positive) victory. Several of the artists featured also used laptops or other digital technology and are not as absolutist as the film might suggest.

It’s a powerful document of one strand of electronic music and sets a high standard for future films on the subject but it also points out the need for other narratives – stories from (to name but a few) the pioneering electronic music studios of Paris, Warsaw or Tokyo. Another (admittedly predictable) reservation is the lack of female voices in the scene. Without being tokenistic it would have been relevant and interesting to hear from voices like Laurie Spiegel or Eliane Radigue.

Even so, there’s much fascinating material and the film adds greatly to the history of electronic music. Although it’s ultimately very much a film by, for and about true believers, there is much to be learnt from the film, even if you have a more agnostic or sceptical attitude to the technology it celebrates.

More info on I Dream of Wires, including details of how to purchase the film, available here.

From Speak and Spell to Laibach.