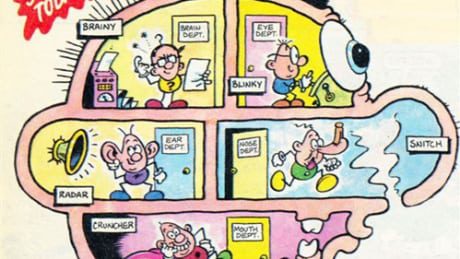

The Beano, ‘Numskulls’ (c.1960)

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;]A[/dropcap] famous philosopher told his infant daughter that the crocodile she had dreamt was in her head. Terrified, that there was a crocodile in her head, she became much discomforted.

It is a first shot at mental imagery, to explain it in terms of images in the head.

Pre-philosophically, it appears as if we have pictures projected onto our inner skulls which some homonculus sits and watches. It cannot be so.

Where are mental pictures, if not in the head?

The answer to that requires some thought. Imagine your mother. The ‘image’ of your mother is your mother brought to mind, in a special imaginative sense. That is to say that she ‘appears’ to you in terms that can only be phrased in perceptual language.

It is as if you see her, perhaps in the garden, stooping as she weeds the flower beds.

In that case, the image is in and of the garden; and your mother ‘appears’ there and then – wherever there or then were. Of course, if I only imagine a woman (unspecified) stooping and weeding in a garden (unspecified) then the image is fictitious and the time and place are also fictitious. But in this case the image appears as if the woman and the garden are percepts. (They are not.)

Moreover, the image is not a picture at all. It is, rather, a scape of some sort. A scape, that is, in which a woman can stoop, bend down, pull weeds, look up, turn around. It is an inhabited space in its own world.

If you have a mental picture of your mother, then that is a relatively flat rectangular plane that can be turned as a picture can be turned. But that is because a picture is relatively flat and can be turned. Indeed, a picture is just another part of a scape.

The first thing to notice about mental images is that they are ‘gappy’.

You might have formed an image of your mother but be unable to say what colour her dress is in your image. There may be no condition in which you have formed an image of the sky above. Is it cloudy or bright? Until asked, you might have no correlative image detail.

Cleave open a head and there is no corresponding ‘picture’ that matches the image.

Pictures in the head, mental pictures, images are surely found to have a basis in brain activity, but neurons firing and pathways travelled are not pictures, nor are they images – anymore than binary codes and html are the pictures to which they give rise.

The obsession with reductionism – the reduction of higher order mental phenomena to brain states and processes – is a symptom of our age.

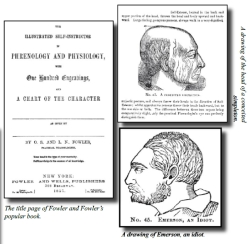

It persists from the early nineteenth century, when it was thought that the curvature of the outer skull could be used to diagnose a criminal nature. That theory has been largely debunked, but beware. Whilst a recent paper empirically rejecting phrenology, as once practiced, extends ‘hope’ that further experiment within the skull might prove successful.

___________________________________________________________________________

An Empirical, 21st Century Evaluation of Phrenology

June 12th, 2018

The old technique of judging people by examining their head bumps gets a new looking-at, in this study:

“An Empirical, 21st Century Evaluation of Phrenology,” Oiwi Parker Jones, Fidel Alfaro-Almagro, and Saad Jbabdi, bioRxiv 243089, 2018. The authors, at the University of Oxford, UK, explain:

“An Empirical, 21st Century Evaluation of Phrenology,” Oiwi Parker Jones, Fidel Alfaro-Almagro, and Saad Jbabdi, bioRxiv 243089, 2018. The authors, at the University of Oxford, UK, explain:

Phrenology was a nineteenth century endeavour to link personality traits with scalp morphology. It has been both influential and fiercely criticised, not least because of the assumption that scalp morphology can be informative of the underlying brain function. Here we test this idea empirically, rather than dismissing it out of hand. Whereas nineteenth century phrenologists had access to coarse measurement tools (digital technology then referring to fingers), we were able to re-examine phrenology using 21st century methods and thousands of subjects drawn from the largest neuroimaging study to date. High-quality structural MRI was used to quantify local scalp curvature….

In closing, we hope to have argued convincingly against the idea that local scalp curvature can be used to infer brain function in the healthy population. Given the thoroughness of our tests, it is unlikely that more scalp data would yield significant effects. It is true that further work might focus on the inner (rather than outer) curvature of the skull, perhaps formalising a virtual method for creating endocasts. In any case, we would advocate that future studies focus on the brain.

(Thanks to Ivan Alvarez for bringing this to our attention.)

(Thanks to Ivan Alvarez for bringing this to our attention.)

BONUS: A special issue (volume 13, no. 4) of the Annals of Improbable Research: “Where in your head?”

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.