Vladimir Putin often claims that Ukraine has no independent cultural identity: it is simply part of Russia. So it should not be surprising that Ukraine’s cultural heritage has been targeted for destruction or removal following the Russian incursions of 2014 and 2022.

“According to Ukraine’s Minister of Culture, as of October 2022, Russia pillaged at least 40 Ukrainian museums. Art looting sometimes follows the shelling of cultural institutions (e.g., the Akhip Kuindzhi Museum in Mariupol), or accompanies the persecution of heritage professionals (e.g., the abductions of the director and curator of the Melitopol Museum of Local History). Some acts of looting, such as Russia’s removal of the Scythian Gold in Melitopol, target the artefacts that are particularly important for Ukraine’s national identity…”

—Protecting cultural heritage from armed conflicts in Ukraine and beyond, report to the Committee on Culture and Education, European Parliament

Most Ukrainians’ misplaced confidence that tensions with Russia would not escalate into all-out war meant that there was a general lack of preparation for protecting cultural institutions and artefacts. Until it was too late.

Fortunately, there were exceptions….

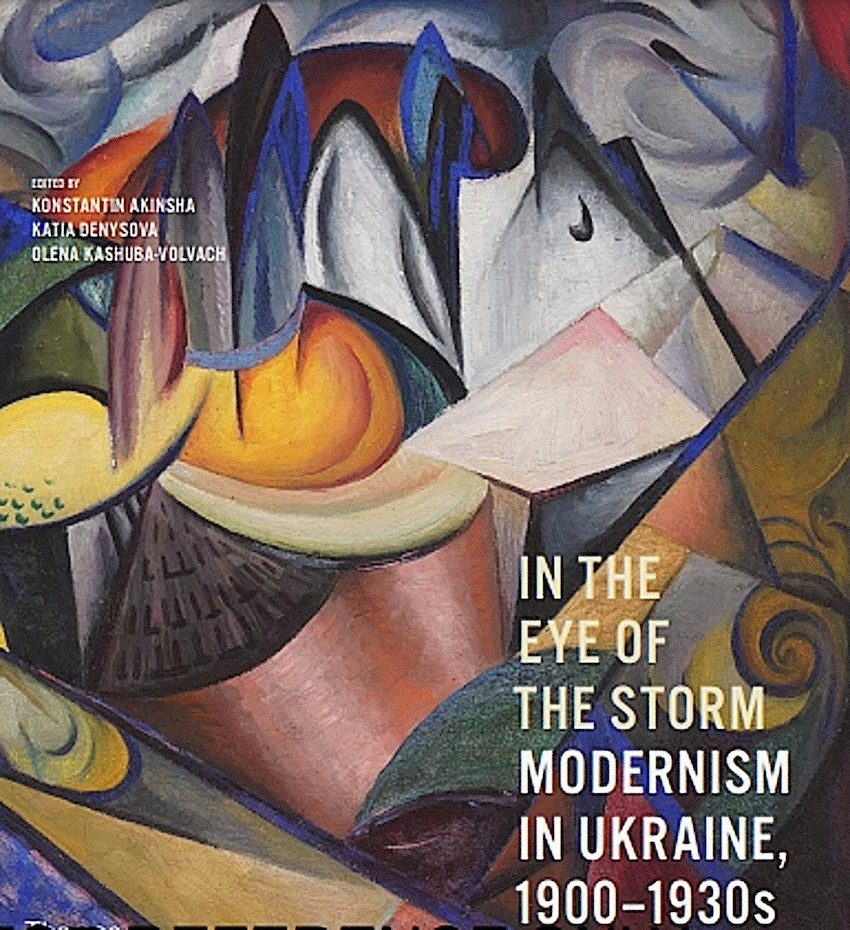

In the Eye of the Storm

The harrowing backstory of the touring exhibition “In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930”

This is an exhibition with a story. I wanted to create this exhibition for a very long time. My first effort was in 2018, when I agreed with the Ludwig Museum in Budapest to do two exhibitions, one on contemporary Ukrainian art and another on early modernist art in Ukraine. The museum’s director was enthusiastic. He promised us two floors in his museum; a beautiful space that could easily accommodate the work.

Everything was going well until, at the last moment, there was a clash between Ukrainians and Hungarians. The Ukrainians adopted a new law on education, which Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, immediately interpreted in relation to the rights of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine. To be even more clumsy, Ukrainians adopted the law just before Hungary’s elections. During that election, two topics were repeated constantly: George Soros and the new Ukrainian law. The result was that Hungary put a freeze on all state sponsorships connected to Ukraine, which included, of course, the insurance guarantees which were necessary to make this exhibition possible.

In the end, we still produced the contemporary art exhibition. It was very successful, despite the fact that no Hungarian officials attended the opening. Ambassadors from the United States to Mexico sat in the first row. That was good, but it didn’t satisfy my continued desire to stage an exhibition on Ukrainian modernism. I tried to do that for a few more years. At one point, I visited an important museum with the representative of a German cultural foundation which was interested in supporting this exhibition. I showed the director my materials. He looked through them and said, ‘That is very interesting, but I will not do this exhibition’. When I asked why, he explained that it was because he was working with the Tretyakov gallery in Moscow and the director of the gallery had told him that if he were to do something with Ukrainians, he would have problems with the Russians.

That was before the current war. I continued knocking on doors, but none opened. Then we came to a situation when war was very close. Americans were saying every day that the war could start tomorrow. Ukrainians said ‘No no no. Nothing will happen’. They did not prepare, and did not give any thought to the evacuation of museum collections. My colleagues in Ukraine who tried to sound the alarm got no attention.

A week before the start of the war, I decided that I would try to do something. I wrote an opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal [Ukraine’s Museums in the Crosshairs, 17 February, 2022], basically saying that war could come tomorrow, it’s time to move. I was hoping that words from America would be more effective than words from Kyiv. It did not help.

Then the war started. Barbaric attacks came, and at the speed of sound, Ukrainians lost museum collections in Mariupol and Kherson. Kyiv was constantly in danger. I called my colleague, Yulia Lytvynets, the director of the National Museum of Ukraine. I told her that I could see only one solution: arranging a travelling exhibition to get artworks out of the country. She was very supportive. But then the question was where to move the collection. The museum started knocking on the doors of European museums. Some were very open and very nice. They said ‘It’s a great idea. Let’s look at our schedule. We can do it in three years’. I said, ‘No. It must be now’.

Soon, I found a supporter—Katia Denysova, a young Ukrainian art historian who was completing her Ph.D. thesis at the Courtauld Institute in London. She became the co-curator and co-author of the project. Our initial shared idea was to begin working on the catalogue immediately, without waiting for an agreement with venues. We put the cart before the horse and somehow we convinced Thames & Hudson to publish a book that could serve as a catalogue for the exhibition. At that time we did not have a venue for the exhibition, so I am very grateful that they were adventurous enough to publish it.

A friend of mine, the Swiss art collector and patron, Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza, was very active during the Yugoslav war of secession, protecting cultural monuments in Dubrovnik. A week after the beginning of the war, she called me.

‘We have to do something,’ she said. But what? She created a WhatsApp group gathering different museum directors. Everybody was very nice, but not very willing to do anything serious. In the end, Francesca basically forced Guillermo Solana, the director of the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, to take this exhibition, because she’s on the board. [Her father built the museum’s collection.]

At first the director was unconvinced. He did not know where is this Ukraine, what is this art, so he only wanted to give us one room. As he looked through our materials, though, his appetite started to grow. He offered us two rooms. Eventually, he removed part of the museum’s permanent collection to free enough space to mount our exhibition.

Getting the Paintings Out of the Combat Zone

So, we had a catalog and a location agreement, but we still needed a way to move the art to the border and then deliver it to Madrid. This was a big problem because there was no insurance company in the world that would insure anything moving through Ukraine during the Russian bombardment. Fortunately, we had professional shipping trucks and professional shippers in Ukraine, because the Austrian company, Kunsttrans, had created a branch in Kyiv before the war. Through intense negotiations, through Francesca’s efforts and the museums’ efforts, we came before the presidential administration. The president provided some planning help and a military escort to take the art to the border.

Every week, on Mondays, the Russians bombed Kyiv. We decided to move the art on a Tuesday. We thought we were very clever. Early in the morning of November 15th, the museum director very quietly started loading the trucks. When the trucks left, she called me and said ‘They’re on the road, I’m exhausted, I’m going home’.

Half an hour later, the largest Russian missile attack yet began against Ukrainian cities, including Kyiv. Fifteen minutes later, a Russian missile exploded near the director’s apartment, waking her up. We spent all day on telephones following our shipment on maps, through all the missile attacks on different towns. It seemed to take a lifetime, but by 10:30 p.m the trucks had reached the Polish border. The drivers called: ‘Thank god, we made it’.

At that very moment, a stray Russian missile exploded on Polish territory and everyone was sure it was the beginning of the Third World War. The Poles immediately started moving troops to the border. Our trucks were stuck in front of the gates, on the Ukrainian side. Through the stellar efforts of Ukrainian diplomats, who woke up every official in Poland (although on that night they were not sleeping anyway) the border guards flagged the trucks through to Polish territory before the gates were officially opened.

When they got to Madrid it was an opportunity for celebration, with all the people from the museums, the technical staff and the drivers. When we began to unpack the paintings, the mood of the Spanish curators lifted further. They had not realized what we were giving them and when they saw the work, they liked it very much.

The exhibition was very successful. The Spaniards projected their experience of civil war onto our situation. Memories of the evacuation of the Prada collection were revived and we got a lot of press coverage.

When we were closing the Madrid exhibition, I tried to create a chain of subsequent destinations. While it was still in Madrid we agreed with the Ludwig Museum to move the exhibition to Cologne. From Cologne we moved it to the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels. I liked the Brussels exhibition very much, because we were in good company: they put our work in the main building, with their “old masters” collection. We had a David on one side and a Rubens on another, and every visitor to the museum came through our show even if they had not planned to see it.

Touring the exhibition has been very interesting for me because I got to see the different ways European museums operate. They are very dissimilar in their approaches, in their abilities, in their finances, etc.

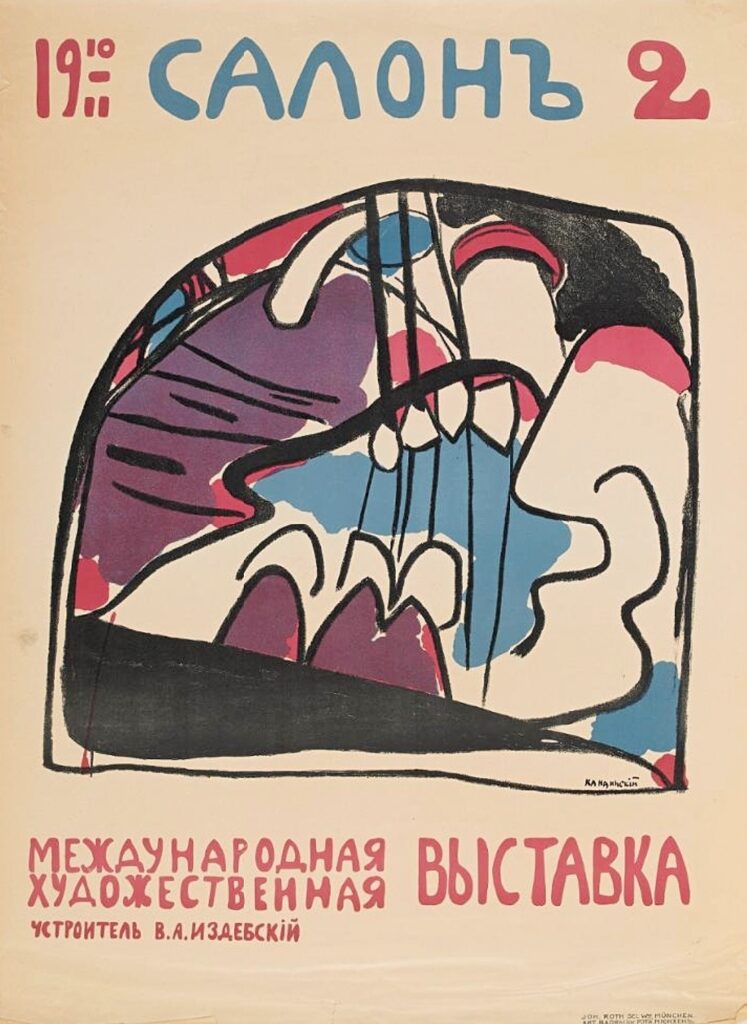

As my appetite grew, I decided to add a second collection to the tour. I wanted to include more art from around 1900. Of course, many of those artists were influenced by what was happening in Vienna and Munich at the time. Many studied in Munich, or at the Krakow Academy in Poland. It was a time of conflicting influences from different centres, which led to the emergence of strange and original styles where you can no longer see the direct influence of Vienna or Krakow.

We organized this second collection and I reached agreement with Galerie Belvedere in Vienna. We united both parts of the exhibition there, where they are now on display. For me, the Viennese reaction was very, very interesting because a majority of Austrian newspapers reviewed the show. But 80% of the newspapers selected images from among the earlier works, especially from the Ukrainian Secession, which evokes parallels with their own experience.

Now, we are coming to our next challenge, because the exhibition in Vienna will finish in June, and unfortunately, the Royal Academy in London does not have enough space for both parts of the exhibition, so they are only taking the work from the Futurist period [1920s] and radical modernism [1920s and 1930s]. It will open on the 25th of June 2024. The other part of the collection will travel to the National Gallery of Slovakia. I am very happy that our Slovak colleagues are brave enough to host the show despite the complicated political relations between Ukraine and their country. From Slovakia, the second part of the exhibition will travel to Bulgaria.

Currently, it’s an all-European operation of endless circulation. And, of course, now we are starting to think about North America. We are conducting some initial talks with a museum there. It will be a long and complicated process.

That’s the logistics backstory. But what about the exhibition? We are living in a difficult time, and it started even before the war. But the war ignited an extreme Kulturkampf [culture clash] between Russia and Ukraine. And, of course, emotionally, the radical Ukrainian approach could be understood: you don’t become a great admirer of Russia or Russian culture when your cities are attacked every day, your people are killed, and Vladimir Putin claims repeatedly that the Ukrainian nation and Ukrainian culture never existed.

But a knee-jerk, cancel culture approach does a disservice to the art. My colleague, Katia Denysova, with whom I’ve been doing this exhibition, my colleagues from the National Museum, and I—we try to avoid this by all possible means. Our exhibition is not called Ukrainian Modernism, it is called Modernism in Ukraine. We are not, for example, taking part in the competition to nationalize Kazimir Malevich, which has become an international sport now. (Seven cities claim him. Even Poland does, because ethnically, he was Polish.)

Our position is different. We are focusing on the artists who spent some time in Ukraine, even if only a little, but who influenced the development of Ukrainian modernism.

To give you an example, in 1918, during the initial stage of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, ideologically the government wanted to protect minorities. This did not work very well in practice, but they had a special ministry dealing with Jewish affairs, etc. And for a few years, Kyiv became a center of Jewish cultural life. It was a cultural explosion. People like El Lissitzky came to Kyiv and exhibited, among many others.

Or take Aleksandra Exter. Exter was Jewish. She was born in Belarus but moved to Kyiv at a young age. She was an extremely strong force in the creation of the Ukrainian version of Cubo-Futurism, and was a bridge to Russian Futurists, in a sense. But more importantly, she was a bridge to Paris and Rome. The people around her, especially her students—she created an art school—got information from her about what was happening in those other capitals. They exhibited their work locally and influenced the artists around them. Ukrainians now claim her as a Ukrainian artist, but Russians are convinced that she is a Russian artist, and the French believe she’s a French artist.

In reality, she left an imprint on all three cultures, but in Ukraine, she became the paramount figure who succeeded in fomenting new radical art. Our focus was on artists—of any ethnicity—who strongly influenced modernism in Ukraine and became a part of the local art scene.

One very interesting artist in the exhibition, Victor Palmov, deserves more attention. Palmov was born in the Russian Far East. He became a Futurist when he lived there, where he encountered Ukrainians who had migrated to the region en masse in the 19th century. Then he met Davyd Burliuk, who was escaping the revolution. The two of them moved to Japan together and spent two years there [1920-1921]. When you look for Palmov on Russian or Ukrainian websites, you’ll probably get around 10 hits. But if you search for his name written in Kanji script, you will get pages and pages of scholarly works in Japanese, because these two artists succeeded, in two years, to foment Japanese modernism and Japanese futurism. Palmov then left Japan for Moscow, but did not like it there, so he went to Kyiv and became a driving force in Kyiv as a professor at the art institute, the founder of large art organizations, etc. He was ethnically Russian, but was part of the Ukrainian art scene.

These are the nuances we’ve tried to show. It’s an interesting branch of the European modernist tradition, which was forgotten because of the Iron Curtain. In this earlier part of our exhibition, you can see that before the First World War, around 1900, we had a short-lived globalization. At that time, all these Ukrainian artists were well known. They were written about in international art magazines, they were exhibiting in Munich, at the Secession in Vienna, in Paris, here and there. And then World War One and the Bolshevik revolution occurred and this globalization was lost. But Ukrainian art remained visible internationally, for example, in the late 1920s when Ukranians were included in the Venice Biennale. Paradoxically, Ukraine had its own representation; the Soviet Pavilion was divided into a Soviet part and a Ukrainian part.

But then… cut, and Ukrainian art is forgotten internationally. The artists became victims of repression. In some sense, the repressions in Ukraine were a bit different from Russian repressions, because in Russia, many of the artists were accused of formalism. But in Ukraine, they were also accused of bourgeois nationalism. They faced firing squads, not so much because of their art, but because their nationality was considered somewhat dangerous.

So far, I’m very happy that we succeeded in getting the exhibition outside of Ukraine. I’m still surprised that we managed to do it. I wrote a short opinion piece for a Swiss newspaper after the first exhibition and said that, unfortunately, our best advertising agent proved to be Mr. Putin.

It was he who made this exhibition happen.

Konstantin Akinsha is an independent art historian, curator and journalist. Now based in Budapest, in 2022 he initiated and co-curated the exhibition “In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s”. [Photo by Matteo de Mayda]