Does installation art need to be re-evaluated before art scholarship hardens it into art history? That this hardening has begun is suggested by the steep decrease in texts uploaded to academica.edu containing the phrase ‘installation art’, from the peak year of 2019 when 689 articles were registered, to just 222 in 2023 – even though this was ‘the institutionally approved art form par excellence of the 1990s’ as Claire Bishop (2005) put it.

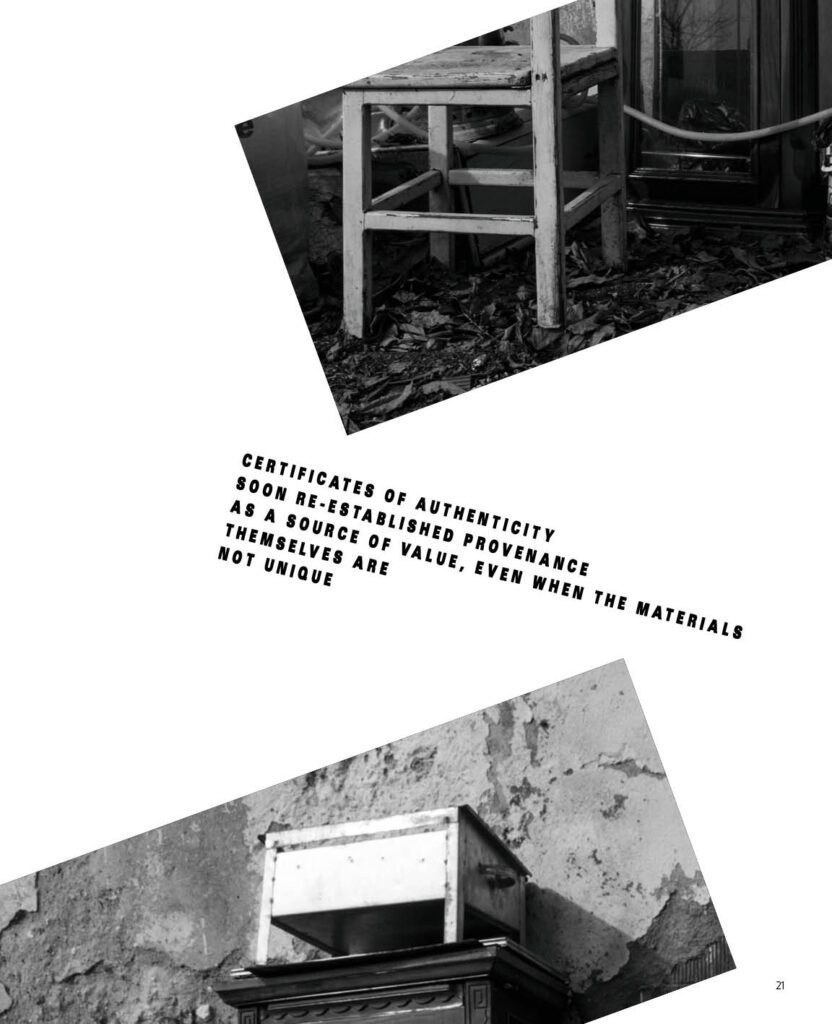

The risk is that this hardening will make permanent the current understanding, which is quite short-sighted. Any artwork which does not originate in the space where it is presented needs to be ‘installed’. And yet, as Bishop points out, there is a ‘fine line’ between ‘installation art’ and ‘the installation of art’: the latter is a curatorial activity while the former is a set of elements arranged by an artist in an exhibition space. What they share is a sense of the arrangement as impermanent. Where they differ is in where the impermanence is―among or within individual artworks―and who determines the arrangement.

But there is a complicating factor: the viewing conditions may be unstable even when the artwork is fixed for posterity. This is the case with “the adorned prehistoric cave”, which Joseph Nechvatal (1999) proposes as the origin of installation art: “the painters of Lascaux took into full consideration the environmental characteristics and qualities of the physical cavern, first by utilising both the encasing ceiling and walls, and then by using the physical bulges and bosses of the stone enclosure to meat out the forms of the animals’ rumps and bellies… These painted caves were presumably meant to be seen by few human beings under conditions of extreme difficulty and apprehension, as many are entered only by crawling on the belly through a hole in the earth down into dark passages in the earth’s womb.”

More recent research by Sakamoto and others (2020) attempts to measure our ancient ancestors’ use of torch lighting, viewing angle and rock surface irregularities to enhance the magical realism of the images that they secreted in caves: “It seems, therefore, that cave walls often played an integral role in the creation and, in particular, viewing of images, and hence that ‘cave art’ was actually a system that integrated the artist/viewer and their physical environment in a two-way relationship that was constantly changing… This relationship corresponds to the principles of modern ‘installation art’…”

However, the importance of cave art was not fully appreciated until late in the twentieth century. So despite its historical significance it was not a major inspiration for the artists who made installation art a widespread practice. Nevertheless, art history is full of achievements… (read the article in full)

Read more in

Trebuchet 15: Installation

Featuring:

Installations as theatre

Giuseppe Penone

Michael Landy

Annette Messager

Karolina Halatek

Sounds Art as Installation

Jean Boghossian

Jon Kipps

Chantal Meza

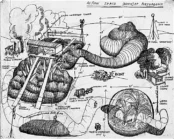

After writing feature articles for Artforum in the 1970s, Robert Horvitz joined Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth publications in 1977 as art editor of their magazines before relocating to Prague in 1991. He has exhibited his drawings at museums and galleries in Europe and the US, including MoMA in New York and Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art.