Two tea bowls upon a wooden tray – a slice of tree; baked earth and hewn wood; cracked glaze – ‘that’s how the light gets in’.

In ‘The Thing.’ Martin Heidegger’s essay concerning the nature of things – as-they-are-in-themselves – we are treated to a poetic meditation on a clay jug. First of all the potter selects and prepares a piece of earth. This clay is then shaped by the potter to be a self-standing jug, a vessel that is filled , and in turn fills other vessels. So, the process of making the jug is determined by our conception of the place the jug must hold in our lives.

The giving of the outpouring can be a drink. The outpouring gives water, it gives wine to drink. The spring stays on in the water of the gift. In the spring the rock dwells, and in the rock dwells the dark slumber of the earth, which receives the rain and dew of the sky. In the water of the spring dwells the marriage of sky and earth. It stays in the wine given by the fruit of the vine, the fruit in which the earth’s nourishment and the sky’s sun are betrothed to one another. In the gift of water, in the gift of wine, sky and earth dwell. But the gift of the outpouring is what makes the jug a jug. In the jugness of the jug, sky and earth dwell.

The gift of the pouring out is drink for mortals. It quenches their thirst. It refreshes their leisure. It enlivens their conviviality. But the jug’s gift is at times also given for consecration. If the pouring is for consecration, then it does not still a thirst. It stills and elevates the celebration of the feast. (Heidegger 1971)

And the wine in the jug is our grasping at the vine which grew out of the earth, nurtured by the sun under the sky and it has been processed by us from grape to elixir; so that both jug and wine symbolize our dwelling in the world.

Perhaps ‘poetic’ is the wrong word here. For, I can imagine the jug being the topic of a piece by Francis Ponge who might abjure this language as far too purple. Yet Ponge’s poetry itself seems to single out the strangeness of – well – things. And this strangeness includes us.

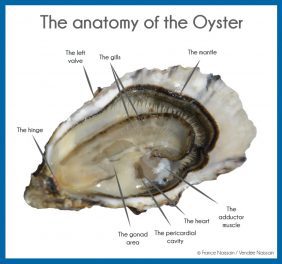

Ponge is one influence, amongst others, on Jane Bustin’s fine art practice; and her work often takes one of his poems and then makes a ‘something’ that suggests the ‘somethings’ he writes about. The scorched silk with its darkened edge readily brings to mind the mantle or pallium of an oyster, its strange slimy burnt-umber hem from which we might ordinarily recoil. (We have to learn to enjoy oysters.)

Wikipedia: ‘Anatomy of an Oyster

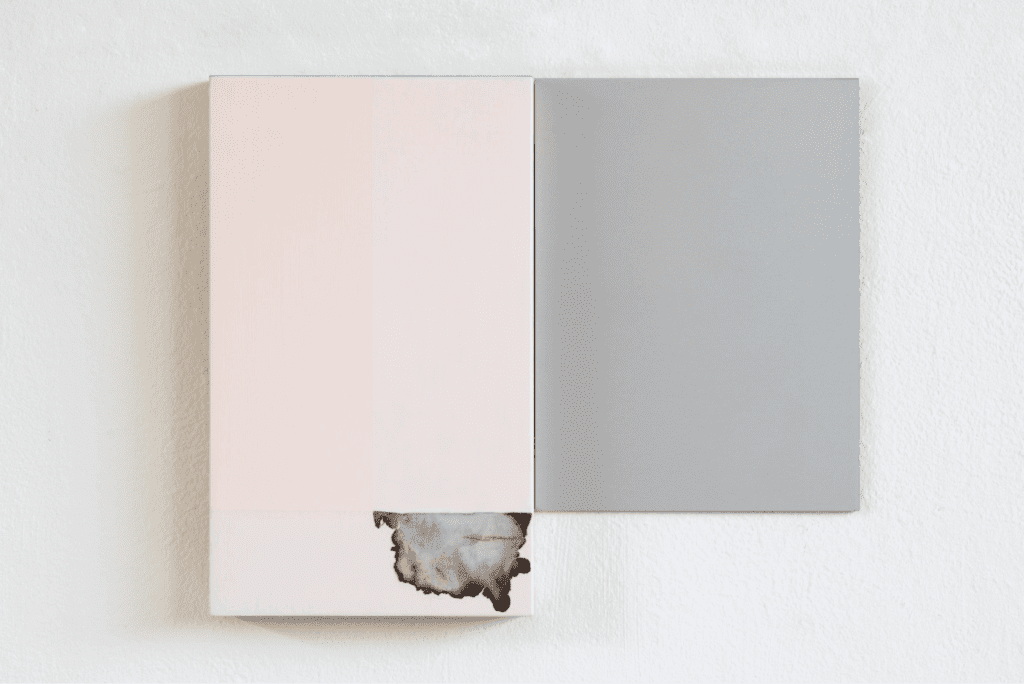

Jane Bustin, Mother of Pearl, 2019

Jane Bustin, Mother of Pearl, 2019

wood, acrylic, anodised aluminium, burnt cotton

Jane Bustin, Oxblood, 2019

Bustin’s work at le sentiment des choses in the Marais is both beautiful and meditative. The gallery is best known for its exhibitions of Japanese ceramics; and this show calls upon an aesthetic that might well include the Japanese tea ceremony: ‘After the serving of thin tea, guests may be allowed to take a closer look at objects in the room.’ Fittingly, there are some of Bustin’s wall pieces (painting and assemblage) to add quiet.

Reference: Heidegger, M., (1971), Poetry, Language, Thought, New York, Harper Collins

Jane Bustin is at le sentiment des choses until November 3

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.