New York-based, Australian artist Jessica Rankin combines paint, embroidery and fragments of text to create uniquely textured canvases that explore memory and intuition, and more recently, desire and tenderness.

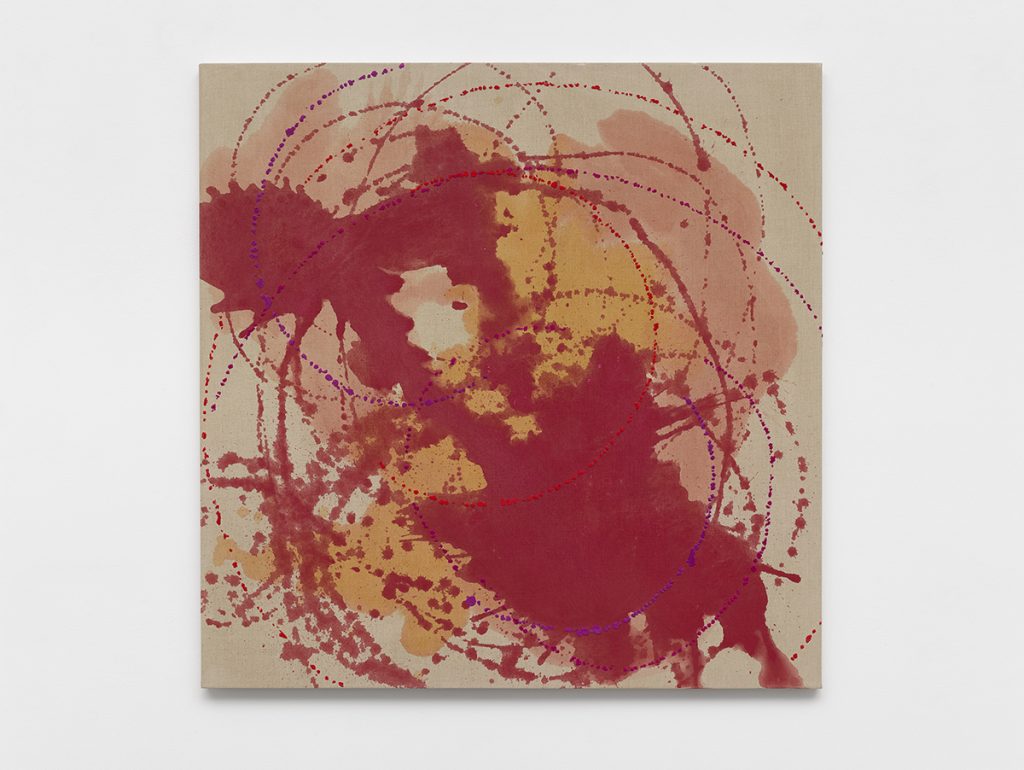

The artist’s latest body of work, currently on display at White Cube Bermondsey, marks a recent shift towards vivid colour and new forms of abstraction in which rapid, spontaneous gestures and the slow process of embroidery collide in beautiful juxtapositions that appear at simultaneously urgent, forceful and fragile.

Here, the artist discusses her relationship with language, complicating notions of authenticity and searching for a sense of unfamiliarity in her work.

You’ve talked before about your work ‘embodying thought’. How do you capture something as transient and fluid as thought in a static medium?

In my earliest work I was interested in the idea that I could somehow capture the nature of thought in material and practice. I was reading Virginia Woolf, interested in the ways in which she wrote to capture the quickness or fleetingness of the thoughts that run through our days as well as the ways in which they are layered and overlapping. And I was looking at a lot of calligraphic work, specifically Chinese calligraphy. I wanted to find a way to convey the feeling that thoughts can be both insubstantial and weighty. Certain thoughts can torment you and repeat endlessly in a loop in your head and yet, they have no physical presence.

At the time, I was embroidering on a diaphanous organdy. I embroidered long repetitive sentences on this barely-there fabric often one on top of the other until they became illegible. The time spent working on the language – the words which could be picked out and then lost again, the ways in which the words were somehow both overwhelming and also, fragile and insubstantial – was my way to try to capture the nature of thoughts and of thinking.

Aside from creating artworks, do you make any other attempts to record your experiences and memories?

I have kept diaries or journals on and off over the years. I haven’t for a long time, though. I think when I was younger, they were an important way to try to understand who I was in the world and try on different personas. I don’t feel the same urge to do that now. I keep things, objects, from almost everywhere I go: talismans, stones, shells, sand, earth, driftwood, flowers or leaves left in the pages of a book. These things hold powerful narratives, and they feel like messages from the past to our future selves.

What inspired you to incorporate embroidery and needlework into your practice?

I was always very interested in the work of the 70s feminist artists, in the post modernists, in artists that painted on, or used found objects. My father is an artist, a painter, and growing up with him and spending so much time in his studio meant that I had a hard time finding my own ‘language’ in paint. I was also attending the University of Melbourne studying history, so I didn’t have a lot of time or space to start a serious studio painting practice. It made sense to step away from painting all together to experiment with other media.

I learned to embroider at a young age and gradually my fascination with the medium grew. I think it was a combination of discovering all the ways I could work with it and some of the art history classes I was taking at the time where I was able to make in depth studies of artists like David Hammons and Coco Fusco. I started to feel that this medium was a gateway to a different way of thinking about making.

There has been a certain snobbism around craft practices such as embroidery. Why do you think that is and are attitudes changing?

I think that it has been well documented and examined that the fibre arts have been relegated to a “lesser” place in western art history. They have had the connotation of the domestic or the feminine. That said, throughout the 20th century, there is a long, rich history of artists working with fabric, weaving and embroidery. The feminist artists of the 1970s made it a part of their practice to redeem fibre arts as a material and to insert them into a “High Art” context. Artists like Faith Wilding in Women’s House or Elaine Reicek (who has made a career of investigating the metaphorical potential of embroidery and weaving). In Soviet Europe, Magdalena Abakanowicz made monumental weavings in a radical subversive act – making art that wouldn’t be censored or corralled as propaganda by the state. Dorothea Tanning’s psycho-sexual felt sculptures feel like precursors to Sarah Lucas. In the 80s, artists like Mike Kelly continued the work of these pioneers. Ghada Amer, for instance, mashed together embroidery and pornography.

With each generation the possibilities of the language are expanded, and I think, finally, in the last five or so years there has been an explosion of younger artists who have come up with all of these artists as examples and for them, and perhaps finally the art world, the classic divide between the disciplines is becoming less and less important. I think MFA programs that have eradicated the need to choose a discipline have had something to do with this along with Queer theory, the desire to investigate the racial and gender hierarchies of the gallery and museum systems, all of these urgent and important questions which have upended the accepted order of things, materials included.

The fabrics you employ are often diaphanous and sheer. What appeals to you about those particular qualities?

With my earlier work, I wanted the heavily embroidered areas of the pieces to exist in contrast to the fragility of the base fabric. I liked the fact that often the shadows of the embroidered areas became as much a part of the piece as the thread itself. The sense of something being heavily worked upon and laboured over and yet, having almost no physical body was interesting to me, and related to my ideas around the weightiness of thought.

Randomisation seems like an important part of your process especially in your handling of text. Are you suspicious of narrative structures or categorisation?

My relationship with language has evolved over the years. I think that my earliest uses of language involved a kind of obliteration of narrative as my interests lay in examining thoughts which so often didn’t have a coherent, sequential form. They behaved erratically and repetitively at the same time, and so often ended up overlapping and disrupting each other.

My mother was a poet, and I grew up in a house of readers and writers and at a certain point I started to think more about poetry as accessing the same kinds of places that I was interested in describing in my language landscapes. I cast my language net wider, incorporating found language as well as my mother’s poetry and my own writings and then used the cut up technique to try to allow the language to reveal itself. I loved the freedom of composing this way and the brilliant juxtapositions that emerged.

With this most recent body of work, I have found myself making paintings that speak to joy and desire. Making them has felt profoundly personal, but I have kept thinking of the ways in which joy and desire runs through the language of the poets I love. Desire, intimacy, tenderness all feel like powerful places of resistance and world building to me. It felt important to use the voices of other people in this work. The words of these writers are generative to me, and my own work exists in conversation with them. I wanted the words to come from communities for whom tenderness, intimacy and desire have always been a place of refuge and a place of full expressive potential. Queer communities, women, people of colour in all their intersections and interplay.

Your latest works employ paint in vibrant splashes of colour while many of your previous artworks have been quite muted. What led this decision, and what role does colour typically play in your work?

I have always felt that my work exists in conversation with the language of painting. In many ways, my works always operated as paintings and I actively tried to capture some of the language of the brushstroke and paint in my use of threads. With each body of work I made, I moved closer to painting and in 2017, I had an exhibition at Touchstones Rochdale which, to me, pushed the work as far as it could go before it had to tip into actual paint. When I started painting, I hadn’t worked with stretchers, linen or paint since I was a teenager, and I had a strong sense of being wildly out of my depth, but there was something exhilarating about that. After many years of developing a language and body of work, I suddenly had no idea what I was doing. I tried to keep myself in that state of unknowing for as long as possible, holding onto the Cageian adage to “be unfamiliar to yourself”.

One thing that I found interesting was that in tipping over into actual painting, I was able to make the conversation between embroidery and painting more explicit. By mimicking and echoing each other the paint and the thread can explore the hierarchy of gesture and materials. They both play with the ideas of quickness and slowness. A splash of embroidered thread shoots across a surface in a mirror image to the paint splash in another work and so which one is the ‘hero mark’? Which one holds the ‘authentic expression’? I love playing with the places where the paint and the thread meet, specifically where the paint meets the edge of the stretched surface. After years of working on thin fabric, the very body of the stretcher feels like a sculpture to me and so the sides of that paintings became as much a part of the painting as the surface. I found that the language could sit there far more comfortably – like the spine of a book.

Colour was especially thrilling and fraught for me. For years my palette had become ever more muted and restrained – I think particularly as I had a sense that I wanted to thwart what was expected of embroidery: its beauty and decorativeness – and so it felt quite hedonistic to suddenly unleash these vibrant colours. I made a very conscious decision to not even bring any of my usual colours into the studio as I didn’t want to have anything familiar or comfortable to fall back on. Funnily enough, working with the vibrant paint has meant that the embroidery has been similarly unleashed and is far more liberated and exhibitionist than in the works that were purely embroidered.

These new works were made during an unhappy time both geo-politically, and personally. The 2016 election had happened, and the world felt full of horror and yet, in my studio these works spilled out of me. I thought more and more about my desire to make paintings as a way of world building, of safeguarding and maintaining self. I thought about the ways that people have done this throughout history – queer people, people of colour, women. It felt important to me to bring the language of others into this work and so I drew upon that in the making of the work too.

What are you currently working on?

I’m currently back in the studio, and starting to paint. It’s a new body of work so I’m trying to feel my way forward, but also not rely too much on what has been made before. Right now, it’s a process of experimentation, false starts, illuminations and connections.

‘the nostalgia for the infinite’ by Jessica Ranking is currently available to view on White Cube’s website until 1 May. The physical exhibition opens at White Cube Bermondsey on 13 April and runs until 1 May 2021. For more information, visit: whitecube.com/exhibitions/exhibition/jessica_rankin_bermondsey_2021

Featured Image: Jessica Rankin, Strange Currents, EA, 2020. Ink, acrylic and embroidery on linen 72 x 96 in. (182.9 x 243.8 cm) © the artist. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis)

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.