[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]t is a refreshing change to be reminded of the political power of music.

Not in a charity single, Bono sponsored, Akon fights ebola sort of way, but as a genuine sense of the potency with which it can communicate a message.

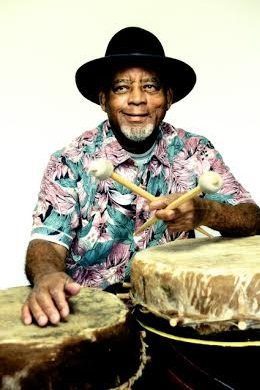

When Julian Bahula tells you music contains the power of revolution, that it is “a weapon for the struggle,” you believe him.

Bahula’s name deserves to be much more famous than it is. This is the man who was instrumental in the new direction in African jazz in the 1960s, who played a vital part in helping Mandela’s imprisonment become symbolic of the struggle against apartheid in the 1980s, and whose club nights in London brought legends such as Manu DiBango, Fela Kuti, Hugh Masakela and Youssu N’Dour to the UK, often for the first time.

But when you speak to the man himself, now 76, it is clear that it is “the struggle,” as he calls it, to which everything always returned, and returns.

When he arrived in London in 1973, having been chased out of his native South Africa, he went straight to join the ANC, and began what was to be a long relationship with the anti-apartheid movement.

“I told [them] that the way forward was to use music as a weapon,” he says. “With music, you could draw bigger crowds.” It was all very well, he said, “telling people standing in the street yeah, yeah, yeah… but if you have music, people want to listen to the music and then they will hear what you have to say, [they] will listen to what is happening to people in our country.”

And so began a decade of touring around the UK and Europe, performing only for expenses to help the anti-apartheid message spread. “We stayed with people, we didn’t stay in hotels,” he says, “boat to Holland, then to Germany by bus, then to Denmark… we did that for the struggle”.

He talks as if it is just obvious he and his bandmates would have done this – that it was the only choice, “because these people, they were also working hard for our freedom”. He is full of praise for all those involved, especially Mike Terry, who led the anti-apartheid movement in the UK for 20 years and died in 2008, but also “good guys like Mike Rose…” [who now plays with Jools Holland] and Steve Scipio.” This pair, despite not being South African, “took our struggle into themselves and they helped. I really appreciate what these two guys have done for our freedom.”

Without everyone who was part of all that, he says, “the struggle would still be going on”.

And in 1983, he decided to do something bigger.

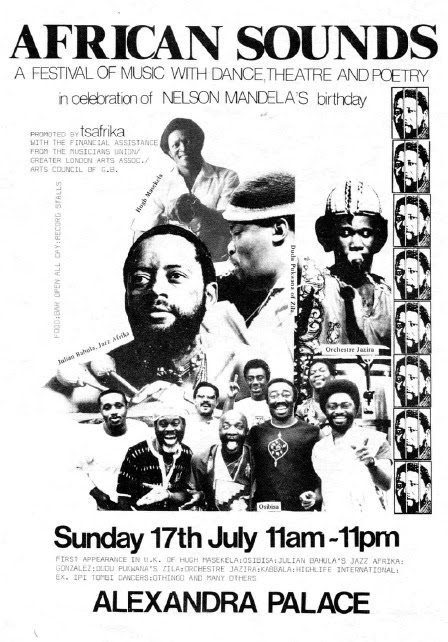

That year, to mark Nelson Mandela’s 65th birthday, and his almost 20 years in prison, Bahula and his wife Liza decided to organise a concert, at Alexandra Palace in London. This was the key moment he says, looking back, in raising awareness – of the struggle against apartheid, but also of Mandela’s name.

It is no exaggeration to say that that night, almost ignored by the press, was a key moment in securing Nelson Mandela’s release. As well as directly leading to the famous “Free Nelson Mandela” concerts at Wembley a few years’ later (organised by Mike Terry), and helping to cement his symbolic importance, Bahula’s performance of a song he had written called “Mandela” was also witnessed by Jerry Dammers of The Specials.

That inspired “Free Nelson Mandela”, which became an anthem that Bahula says “helped a lot for Mandela’s release and for our struggle.”

The event was a huge success, belying the pair’s concerns that they might not make the £2,000 they needed to break even. The event also “made Hugh Masakela’s name in Britain”, after Bahula approached the now legendary trumpeter to perfom. At the time, he says, people in the UK had heard Masakela’s music, but they’d never seen him live. He was a star in America, but, “He said, for Mandela, I’ll do it,” and did – for nothing but the plane fare and a night in a hotel.

Again it always returns to that – using music as a weapon. The nights at the 100 Club in the 1980s, and later the Forum that did so much to promote African music in the UK? “I went to talk to Mike Terry and told him I would like to do things at the 100 Club, and you could do things at the same time, give a speech you know.”

Roger Horton, the club’s owner, was immediately on board. He said, “Let’s try and see if it works”. And he was happy for Mike Terry to speak – “No, I don’t mind, he said, because people are struggling in your country. He was a good man.”

“We did well for the 100 club, and also for promoting our struggle,” Bahula says, but it “was getting small for the things we were doing” pretty quickly, and so they moved on to the Forum. At the time, it “wasn’t a music venue at all”, but it soon became “a brilliant place”.

“We brought Youssu N’Dour for his first performance in the UK… also many [musicians] from French speaking countries. Fela Kuti played and Hugh Masakela…” he says. Not to mention Lee Konitz, Archie Shepp, Pacquito D’Rivera, Manu DiBango….

But the reason I am talking to Julian is not because of his role in the African and jazz music scenes in London in the 80s (“music… music was really happening then”), but because of a new double album of his own music (The Spirit of Malombo) that has just been released.

Here again, Mandela’s name comes to the fore. “For us, it was just so much… that year 1964 was the year that Mandela was jailed. And we came out in 1964.” In that year, Bahula won first prize at South Africa’s Castle Lager Jazz Festival as part of the Malombo Jazz Men, and in the process helped to move South African music in a new direction.

“We came with a different thing that sounds traditional and turned into a jazz thing,” he says. “Our sound was more raw… Most musicians, they were copying American jazz music. And we wanted to come with something original from Africa, based in what our forefathers were doing.”

Part of that came from Bahula’s use of the traditional malombo drums, which give a drive and groove to even the most laidback recordings from that era.

It worked. But success was a mixed blessing, as it could only be under apartheid. “We couldn’t play where we wanted, by 9 o’clock we were supposed to be out of the city…. [quote]It was a good thing to be honoured –

mostly for fighting for freedom[/quote]We couldn’t play in night clubs”. The band were barely paid anything for the records they produced, and as they got more popular, the level of harrassment from the authorities increased to such a level that Bahula and his bandmates were forced to constantly change addresses to stay one step ahead.

Bahula managed to get a visa in 1973 as part of the white fusion band Hawk (he had to wear a mask on stage during gigs in South Africa to hide his race) and used it to escape to London. Guitarist Lucky Ranku followed a year later.

Neither would return until apartheid ended.

Returning to that music is clearly an emotional experience. “When I hear that music it reminds me of those years in the 60s,” he says, adding that he would love the chance “to play with the guys that I worked with on this album, to promote this music. Because we never had the opportunity to come out of the country, out of South Africa those years, and now there are many people who haven’t heard that type of music, and I’d like to present that music to the people and the world.”

I ask him which was more important – the politics or the music? He laughs, and says

“Both. I am really very fortunate. This [the album] has brought back a lot of good memories for us and the people in South Africa.”

Bahula was honoured by the South African government in 2012, the ANC’s centenary year, and it is clearly hugely important to him. But although he says, “It was a good thing to be honoured – mostly for fighting for freedom,” he is concerned at the direction in which his country is going.

Again, Mandela is the touchstone.

“The way we were oppressed in the past, to live together as people… for Mandela to have done that… to say that South Africa could be a rainbow nation. I wish our leaders, they follow Mandela’s steps… This is my wish. He spent so many years in prison and for him to see our country as a rainbow nation without any problems or revenge – to say you did this to me and to let it go… we should follow where he led. I just hope it will continue… But people are people. They change, and forget. But it’s not good for them to forget what Mandela went through.”

He says he hopes the album, which covers both the years in South Africa, and the first decade after he came to London, will help. “Things are not going well in our country. So it [the album] should be a bit of an awakening for people to remember and think of other people as people.”

That is the “Spirit of Malombo”, he says, to always remember other people as people. But that spirit is also about keeping the memory of the struggle and all that it achieved alive. The album, and the autobiography that Bahula is working on will undoubtedly help this, and once you’ve heard his story it’s hard not to be in awe of this man’s lifetime of commitment.

And, on top of all this, the album is fantastic. From the pared down jazz of the early years, to the funkier, more expansive Jabula and Jazz Afrika recordings, this is a musical legacy that deserves to be heard. And that just makes you hope that Julian Bahula gets his wish – to take to the stage with Lucky Ranku again and bring the music, and the story back to the world.

That, after all, has always been what he’s done. Hook people in with music and use it to get them to listen.

Music as a weapon. It’s good to be reminded of that.

[button link=”http://www.strut-records.com/tag/julian-bahula/”] Julian Bahlua – Spirit of Malombo[/button]