[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]”There[/dropcap] is no perfection, only life….” More than sixty years before Milan Kundera wrote these words, Kazimir Malevich was rebelling against the perfection by which life was defined.

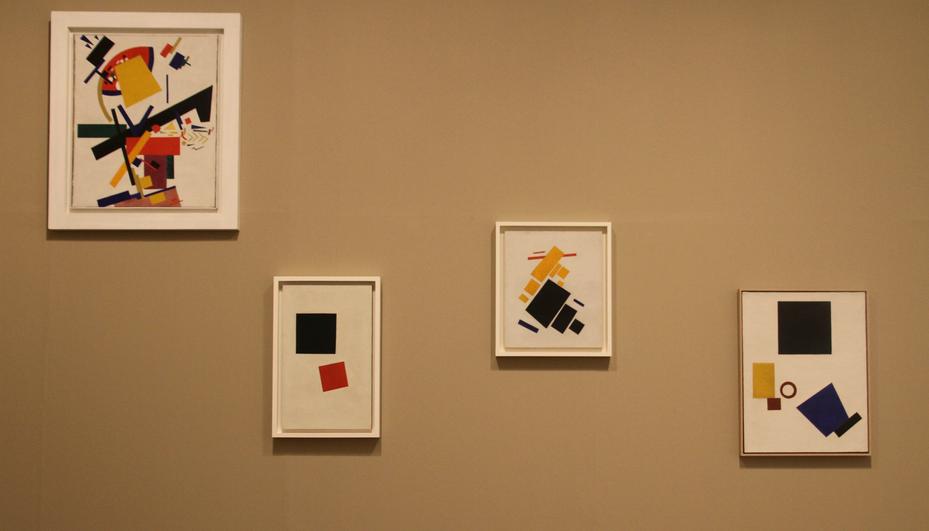

His work completed the troika, combining poetry and music, and was developed into a purely abstract form of expression: Suprematism. He undressed art of all preconceptions inflicted upon it throughout centuries of religious, social, and mental colonialism. And his art stands there, bare, naked, and proud. It overshadows any form of representation and reaches out to us as a pure unadulterated feeling.

Today, civilians are dying in Palestine, in Syria, in Iraq, and regardless of it being a consequence of Vladimir Putin’s defence mechanism or aggression, civilians are also dying in Ukraine. And today, the Tate Modern is holding a retrospective of Kazimir Malevich’s lifetime contribution to modern art history.

Malevich’s art is intrinsically rooted in Russian politics from the Tsar Nicolas II’s autocratic rule, the outbreak of the first World War, the Bolshevik Communist Revolution, and Stalin’s consolidation of power. At this point in time of Russian politics where the Kremlin is threatened by the conceptual prowess of American democracy, where the fight for Donbass is a fight for Russia’s past and future, Malevich’s works are as relevant today as they were a century ago. And standing there in what could have been a room in a gallery in the Soviet Socialist Republic, looking at Malevich’s ‘Black Square’, we cannot help but ask ourselves, do we live in a society where history is frozen?

Sponsored by the Blavatnik Family Foundation and the Amsterdam Trade Bank, and curated by Achim Borchardt-Hume, Iria Candela, and Fiontan Moran, Tate Modern is showcasing this lasting legacy until the 26th of October, 2014. The Eyal Ofer Gallieries have been divided into twelve rooms spanning the artistic lifetime of Kazimir Malevich. The centrepiece of the show is the Black Square. It is an artwork that holds within it the possibility to infinitely speculate the potential of artistic freedom. It is a coup d’etat in the form of a black square on a square canvas.

Yet to truly appreciate the iconic significance of this piece, we must look at what came before and after it. Starting with his early paintings that were heavily influenced by the Impressionist movement and Cezanne and Monet, and ending with his return to more realist figurative painting (nonetheless Malevich signed these later works with a black square). But this is an exhibition spanning the entire lifetime of an artist, it is much more than experiencing a masterpiece. Every drawing exhibited, every shade of every colour, every shape and every cut-out provides insight into this beautiful mind.

2014. Room Eleven. Tucked away in the top right hand corner are three Russian propaganda posters by Malevich. 1933. USSR. Malevich titles these posters ‘The Results of the First Five-Year Plan’ and ‘The Objectives of the Second Five-Year Plan’. Encouraging collectivism and sponsored by the country’s landlords, they were made to showcase the Republic’s agricultural developments. Did Malevich know that the artistic ideology he developed would be used to serve the demands of Stalin’s economic acceleration?

These posters provide us with direct examples of politically applied art. However, Malevich masterfully created an artistic framework that adapts itself to both convention and change; change in this case was a change towards Communism.

“Anyone who thinks that the Communist regimes of Central Europe are exclusively the work of criminals is overlooking a basic truth: The criminal regimes were made not by criminals but by enthusiasts convinced they had discovered the only road to paradise. They defended that road so valiantly that they were forced to execute many people. Later it became clear that there was no paradise, that the enthusiasts were therefore murderers. ”

― Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

With this is mind, how would Kundera have reviewed Malevich’s work? Was Malevich proposing a political ideology? Probably not. Malevich created beauty; unconventional beauty. He created a beautiful thought that inspires a beautiful feeling; that of freedom. His work is the exteriorisation of the infinite space within our minds regardless of time and space, regardless of whether we are in Gaza, Duma, Mosul or Kiev. Malevich’s work gives us the possibility to transcend our modern definition of reality.

“We, like a new planet on the blue dome of the sunken sun, we are the limit of an absolutely new world, and declare all things to be groundless”

Kazimir Malevich, Anarkhiya

[button link=”http://www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern” newwindow=”yes”] Tate Modern[/button]

Faten Hakimi, Artist and Fine Art Consultant, MA Fine Art City & Guilds www.fatenhakimi.com