[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]M[/dropcap]usic deals with time and timing. It’s so magical, but when you get into it, every little sound and every little space between the sounds, it’s critical, so critical.

And if it’s not there, it not only feels wrong, but it ruins things” – David Lynch

To preserve the intellectual property of music many countries require that it is ‘fixed’ in a medium (usually recorded or written down) that sets its constituent noisy components in a unique order. In a sense this makes the intangible nature of music concrete and thus property. Sound however is a physical force produced by tangible parts directed by the composer to achieve a particular effect. The point where sound becomes music is of course the point when a sonic interruption becomes appreciated and thus art. Part of how people appreciate auditory stimuli is by associating a sequence of sounds with a narrative which contains what they’ve heard in a historic sense. Let’s face it, most of the time what we hear is essentially ordered noise and while we do not consider it music, it’s clear that someone wants us to. Intention is everything in music.

Often we can find music in nature if we listen closely but more often we let go and leave it to someone else whose musical work we’re familiar with. We know how they’ll order the sound, and riding the expected rolls of motif and crescendo, we can lose ourselves for a while.

There are of course other forms of listening (cf. ‘perceptual phenomena’ by Steven M. Miller and ‘sonic awareness’ by Pauline Oliveros) and other forms of music (some confronting musical genres include the term ‘noise’) that push what we recognise as music. Jazz and avant-garde are the two schools of music that have been most closely associated with the quest for new definitions in sound.

Keith LeBlanc was active in the rise of both hip hop and industrial musical genres as they transitioned from underground ideas to commercial industries. His early recordings on drums with The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rappers delight”, Tackhead and a near endless list of production and performance credits on seminal records indicate an artist who is adept at being in the right place at the right time. Characteristics that define not just the best drummers but the most successful artists. Speaking to Trebuchet, LeBlanc explained how he views time and space in music and how truly considering these elements as regimented fixed paths that must be adhered to is where musicians begin.

“Time and space are everything, as a drummer. But musically they’re everything as well, because of the possibilities. The best things I’ve done on the drums spatially is being able to find the right space to leave in the music, so it’s pretty important what you don’t play. Supporting everyone else that you’re playing with, you have to choose spaces in the right place to make it work and leave room for people’s souls to touch. That’s basically what happens when you’re playing real music. It’s a trust thing, it really is, and the space is very important in that.

Keith LeBlancs Top 5 records that show amazing use of time and space

When I met Skip [McDonald] and Doug Wimbish they were already doing recordings and playing in clubs. They already had a record out on All Platinum Records. One of the songs “Funkanova” was used on a news channel in Connecticut. It was like a theme song—it’s off the Wood Brass & Steel album.

I played jazz, funk and fusion at that time, mainly because it was what I was drawn to, and these guys were playing music I liked better than anyone else I could find. [But even so] they spent a long time pulling me into shape. [Initially] I tried to fill every space there was, every spot with a lick. So Skip spent a long time working with me and what he was asking for most of the time was space. I was pretty honed in when we went to Sugar Hill to record. [The process] helped me get further because I immediately heard myself back and was able to have a different objective.

[When I moved to the UK Mano Ventura was another guy who] broke all the musical rules. He’s one of the few true geniuses I’ve had the pleasure of working with. The guy drove other musicians crazy because they couldn’t figure out what he was doing, and yet it sounded beautiful.

He told me that you can get away with anything musically; it doesn’t matter as long as it’s in the right space in time. You can change all the musical rules and that’s exactly what his band consisted of.

Keith LeBlanc’s top 5 inspirational artworks

-

Michelangelo’s Pieta

-

The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali

-

Guernica by Pablo Picasso

-

Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh

-

Nighthawks by Edward Hopper

Every good musician I met in London, they all played with this Mano Ventura. They all had something different with what they were playing, and what it was, was time and space. I saw the musical beyond with this guy, and it just rubbed off on us. After playing with him, I had to choose what not to play very carefully, because I got so used to stretching, I would lose people…”

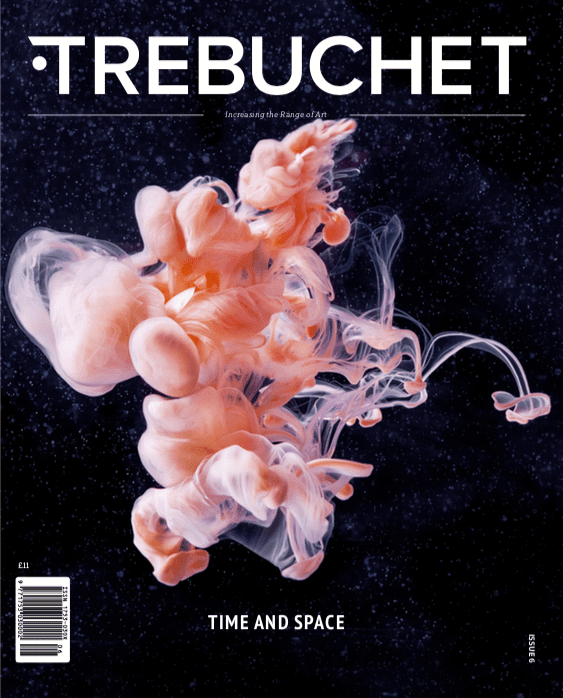

Continued in print. Read Keith LeBlanc in Trebuchet 6 – Time and Space

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle