Born in 1926, performance artist and painter Ken Turner will reach his 100th year next year.

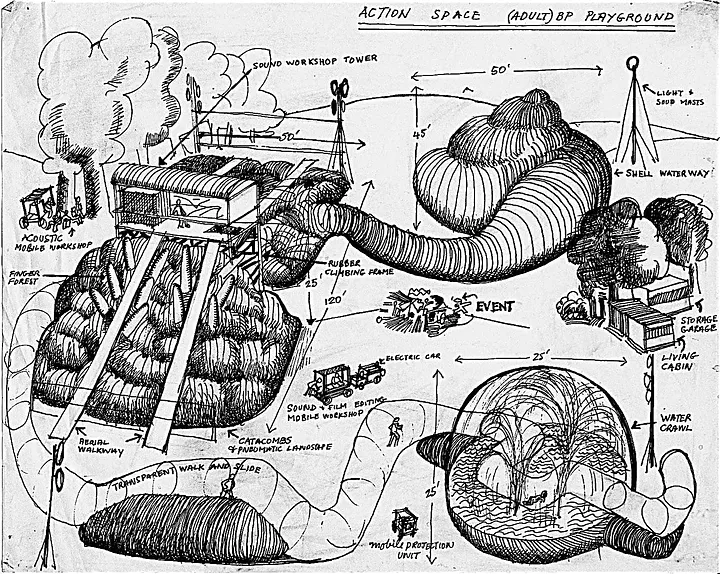

Turner served in the British army during WWII, rubbed shoulders with Ferdinand Leger and Francis Bacon, and was active in the London arts scene until the late ’60s when he co-founded the radical artists’ group Action Space with his partner, the late Mary Turner, rejecting the gallery world of the time. Action Space worked with inflatable structures, early video and participatory performance, housing estates, open air festivals and parks, launching at Joan Littlewood’s City of London Festival in 1968. The group formed at a time when enormous political and social changes were being felt across the UK, and many of its members went on to become influential in the arts and society in general.

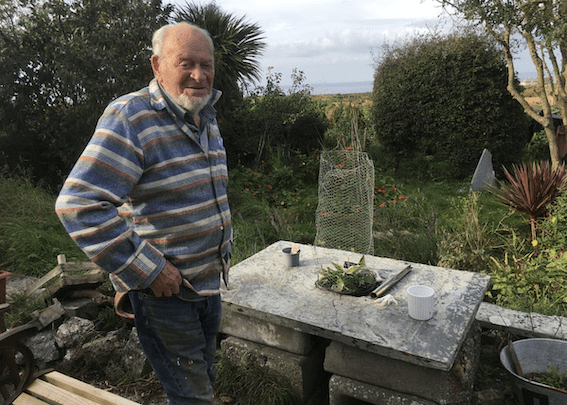

Ken Turner is interviewed here by former Action Space member and curator/writer Rob La Frenais, who joined the group in the early ’70s before going on to edit the ground-breaking Performance Magazine in the ’80s. He spoke to Ken in the garden of his studio at St Ives about his trenchant views on philosophy, politics, performance and painting and why he keeps performing and protesting.

What was the atmosphere like in, let’s say, 1964, 1965, that kind of time? And what did it feel like to be in London in that part of the art scene before you became disillusioned? And then how did the disillusion start to emerge?

It wasn’t disillusionment. It was horror. Horror, horror of what was going on. It’s really quite difficult to think back to that age. I mean, I was, what, 38? I was late coming into the art world anyway. What was the reason why I was late? I think it was because I was running a framing business with Mary. Mary was a gilder and designer. And I found it very satisfying because I had got a place at the Slade and I had got almost a place at the Royal College. I turned them both down and went to the Anglo-French. And remember, that was just after the war. And David Sylvester was the prime critic of the London art world. And he used to come to the Anglo-French Art School and give long, long lectures.

What was the Anglo-French?

It was run by Alfred Rozelaar Green, who had a French wife. And he was quite a remarkable person, really, because he had the foresight to take over this building, which was originally, I think, a flower or horticultural kind of centre. And it was in St. John’s Wood, in this sort of nice environment, large houses and expensive houses and things. I used to have digs in Hampstead. Used to get the tube to St. John’s Wood and walk through into the Anglo-French.

Let’s go back to what happened to you in the post-WWII era. During the war you worked in the mines, then were in the army.

I did my service, as it were, to the country, which I didn’t really believe in. So the army was a horrible experience and I preferred the mines. But anyway, so I ended up in the army opposite Harrods, in a GHQ of the army, doing designs for their building. So, like a lot of other ex-servicemen, I came out of the Army, got a demob grant, went to art school to continue my studies.

The Anglo-French was a remarkable environment because it was unlike any other institution in London at the time. I mean, for the Slade, the Royal College, you have to go through all sorts of rigmaroles to find the person you want to talk to. I talked to John Minton. I didn’t talk to Coldstream. So when I entered into the Anglo-French, immediately I had a cup of coffee, because it was a café — first thing you entered, and the studios were behind, like, a French café. It was really marvellous. I thought, ‘oh, I can relax here’. So I did a lot of painting there. And all these people from both London and Paris came and taught. I had a chat with Ferdinand Leger. He said I was a very English painter. And I said, well, I am English, so what do you expect? Anyway, it wasn’t accredited for a diploma or a degree, so I had to go to the Regent Street Polytechnic. I finished the course and made some good friends there. Well, I refused any kind of diploma.

We know that you founded Action Space in 1968. So what I’m interested in is the transformation of London and England and the arts in that four-year period, during the period you’d call the so-called swinging 60s and the London art world.

You see, I had a good view of what the art world was after the war. I could see it very clearly. I was going around the galleries, talking to them. I was even showing paintings to them. And one of the galleries said, you’re an interesting painter, but we couldn’t sell you. And another said, equally, you’re an interesting painter, you should have an exhibition somewhere. So I was being encouraged to come back and talk again. I was looking at the art world and going around the galleries, seeing what was there after the war, you know what was going on and seeing, you know, people like Francis Bacon and Graham Sutherland.

Joe Tilson showed me around the galleries, introduced me to every dealer he knew, and he knew most people. He was just one of those people who knew everybody. There was Waddington, there was Kasmin, all these galleries. And in the end he said, you didn’t say anything when I introduced you. I said, what do you mean? What should I have said? He said, you should have said, do you want to see my work? I said, no, I don’t want them to see my work. I’m just looking at seeing what the people are like. And somehow I got the feeling, I just got this tremor or sensations that this was a world I didn’t really like. There was something about it which was stinking, actually.

Thinking back to that era and what I was doing, I was fumbling around. I was dissatisfied with the condition of the arts in a sense. I mean, I couldn’t go into some sort of high or deep philosophy about the whole thing. But the gallery that I really liked was the Dover Street one of contemporary art, run by Herbert Read and Roland Penrose. And I met Penrose. I said, can I show some work here? And he said, yes, bring some in. So I took some in and he accepted it and exhibited me in the library. Now, lots of good people showed in that library, and Herbert Read was there, and I didn’t meet him, but I sat next to him. I think I was too frightened to talk to him. Anyway, they showed the work. I had a review in The Times and they said it was interesting and outstanding work or something like that. Then from there I got a show in the Heal’s upper gallery. There’s a Mansard gallery, a big show, almost like a retrospective.

So I had done a lot of paintings and there were lots of abstract work and work that was dealing with the environment and dealing with, also, with devils and angels, surprisingly. People were saying, you’re on the road. You’re on the road to success as a painter. You’re becoming known as a painter. As I had these reviews and people coming into the workshop were talking about it, Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff, and so on, like people like that. And then I had a critic and a painter, Andrew Forge who came into the workshop, wanted something framed and then we talked about painting and showing work. And he said, I’d like you to — I was even then talking about environment. I was talking about outside, beyond the galleries to him. And he said, could you do a Third programme, BBC thing? And I said, yes. And he said, well, Maurice Agis as well was going to do it. So we both talked on the radio about — it must have been after the Lord’s Gallery show, because the Lord’s Gallery show was called Environmental Structures.

So was Maurice Agis already doing environmental structures at that point?

Yes, he was not doing inflatables, he was doing constructions. Using primary colours. He came into the workshop, we talked about it. We were very friendly, he’s really a lovely guy. And Peter Jones also was good. I suppose that was the connection I was looking for. I found somebody that wasn’t talking about the art world, that was talking about something else.

So you met Maurice Agis whilst doing a radio programme.Then he started coming to the workshop. You started talking. So what next? What happened next?

I was teaching for about two or three years at the Environmental Design course in Barnet. And in Barnet I discovered ‘happenings’ in America. So I read Alan Kaprow’s book and that excited me at the time. Nowadays I repudiate it. I think he was totally wrong. But anyway, so there were several influences coming in, and at the same time you had London exploding culturally, in the fringe and you must remember that. So that was exciting. I must say I wasn’t interested in pop culture or pop musicians, but The Beatles meant something. I think they were tremendous. But I would never go to a concert.

Was Yoko Ono around these circles, or were we talking about a different world? Because she was doing Fluxus at that point, before she met the Beatles?

I think I looked upon Yoko as part of the art world. That was where I was guarding myself against this horrible world of an extremely competitive market.

So you saw happenings at the Better Books Basement?

Yes, I saw the People Show, which was something that influenced me. I thought, this is terrific. It’s really getting at the guts and heartstrings as well, of the people, in a way that modern painting just wasn’t. Jeff Nuttall worked with us. He was a great, lovely guy. I mean, all these people were amazing. I even had the People Show asking me to join them at one point.

So here we have a kind of sense of how you’re moving towards the founding of Action Space (and rejecting the London art world). Because the art world also had this very decadent side to it.

Obviously, there were writers like Camus, The Outsider. So the outsider interested me, and that’s what I was. I was an outsider right from my birth.

You met people like Francis Bacon, but you didn’t end up hanging around in that horrible club they all went to?

No, it didn’t interest me. I thought it was just decadent. Well, I wasn’t after wholesomeness, but I was after a sort of pure sense of feeling. I mean, my understanding of aesthetics was very different to what the art world was doing. And the aesthetics actually was part of my moral judgment. Now, that was important. And I read the book, On The Aesthetic Education of Man (by Friedrich Schiller). Do you know that book? It was written in 1795, and he wrote the 26 letters to a client or to a prince, I think it was. Talking about aesthetics and the need for aesthetics to be actually active in your life before you made any other kind of decision to work socially into life. He said that you can’t make a moral judgment unless your aesthetics are established as something about beauty. This was about beauty. And beauty was like a dirty word at that time.

A process of alignment is happening, can I call it that?

I was setting my sights on establishing my own character and personality as strongly as I could with feelings. They were just feelings about something new. And on the BBC programme, I talked about the new sense of image-making in different ways other than the art world was doing it. Because it was linked with politics, it was linked with social ideas. And I do have a social conscience, but I wanted to balance that against the aesthetics of painting as a way of image-making. And that was my struggle right from the very beginning, and went through Action Space, actually and still is prominent in what I do. That is, the visual aspect was extremely important.

You’ve laid out the influences from books, reading, personalities, BBC programmes. Andrew Forge.

Forge was looking for something different as well, even though he was a painter himself, but quite a conservative painter, if I can use that term. Not a rebel or revolutionary in any way. I was saying to myself, I suppose I’ve got to find this path. I’ve got to find this way of opening up something where I can operate fully as an artist in the environment. To do that, I had to carry out some experiments and those experiments were happening in Barnet where I was teaching environmental design. I asked the people there teaching, I said, what is environmental design? And they said, there was a rather lame painter who said, oh, it’s about doorknobs and what’s happening in the environment. I said, well, what is happening in the environment? So I said to myself, why not environmental art? Because of Kaprow I started to think big to make things happen.

So, there were other painters in New York also doing happenings. I got heed of those, and I thought, that’s really interesting. Sort of breaking out of painting and making it three-dimensional and making it environmental. Wow. So there it is, that’s what I wanted to do. So I got these students to actually do this, not from painting, but from design. So I looked at the Bauhaus, which also had a great influence on me because it was dealing with art and architecture, and architecture is dealing with the environment. I saw this film from the Bauhaus and the Triadic ballet, and it was from, I think, Paul Klee, Kandinsky and so on.. This ballet was another sort of impetus to do something different, because it was ballet, but it was structure, it was sculpture use of space, use of form, colour, movement, music, everything. So it was total theatre in a sense. That’s what really interested me.

Now, what did you do? What actually happened?

I made sculpture, which I put into Lords Gallery. So that was like models of the environment. And I was working in PVC plastic which you could mould it, you could form it, you could weld it, you could stick it. So I made these things. But they were three-dimensional forms, and most of them are kind of destroyed now, but I’ve got photographs, and they were looking at the space for performance, because I began to think about theatre and that’s where I came in contact with Joan Littlewood. So the idea of theatre and the environment began to come together and aesthetic form. So not forgetting that idea, that idea of aesthetic form has to happen before any kind of judgment, right? So that was in my head. So that kept me thinking about aesthetics and what form that would take was a driving force or a foundation for how my actions would develop. So I remained an artist. That’s the only way I was clinging on to being an artist, but a different kind of artist, not somebody who showed in the West End galleries.

So there were other examples of people of what you would call different kinds of artists coming together at that time.

Yes they were coming from performance, construction, and inflatables from architects like Jeffrey Shaw. So the culmination of all this happened in that show in the City of London, where I put up a structure using inflatables and rigid objects. Structures. Then when I was there, in that space that I’d constructed, I think I saw the possibility of performance happening within a structure that I built. So I was building my own theatre aesthetically, still there. Actually, people came. Some artists came into that space when it was there for two weeks, I think and they came into that space and performed. Somebody came and did performances, like tearing up paper or very simple things. But I could see that’s where performance was growing in my own mind. Could I do it? Could I actually perform in my own structures?

[Interview to be continued]

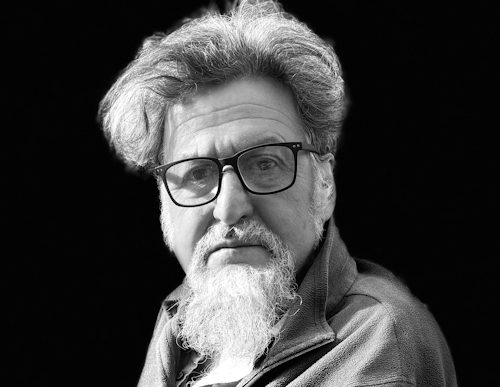

Rob La Frenais is an independent curator, artist, writer and lecturer and works closely with artists on original commissions. He founded Performance Magazine in 1979 and became an independent curator specialising in performance and installation in 1987 and continues to work and write internationally.